Like most twenty-somethings, I am in possession of a 100 year old amniotic sac. Thanks to this slice of dried-out tissue, I’ve never feared drowning.

As much as I’d adore to leave this post as simply the tag-line alone, I feel some context is needed.

My preserved piece of amniotic sac is what is commonly referred to as a ‘caul’ and is only marginally weird. Stick with me.

A caul is a piece of the amniotic sack that is attached to the baby’s person after birth. Many accounts make particular reference to its presence on a baby’s face; hence, why a caul birth can also be referred to as being ‘born with a veil’. The caul may adhere itself during birth or gestation, but the effect is the same and most ae easily removed by simply peeling it from the baby’s face/person after birth.

Nowadays, a caul birth is incredibly rare, with estimates sitting around the 1 in 80,000 range. Some very patient midwives who endured my questioning all agreed that en caul births are ‘almost always premature births’.

A more specialised birth with a similar root name is that of an en caul birth. Despite incredibly rare and requiring specialist intervention, images of such babies are frequently shared across medical social media accounts. An en caul birth is when the child is delivered within a fully intact amniotic sac. Understandably, these images are very striking and are frequently misinterpreted by non-specialised media outlets. It should be noted that as dramatic as these photos are, medical professionals usually rupture the membrane artificially, immediately prior to delivery if it were intact. This means that the baby’s airway would not be obstructed, avoiding further risk of trauma. Understandably, this was not a possibility in years gone by, hence why caul births were infrequent but not completely uncommon.

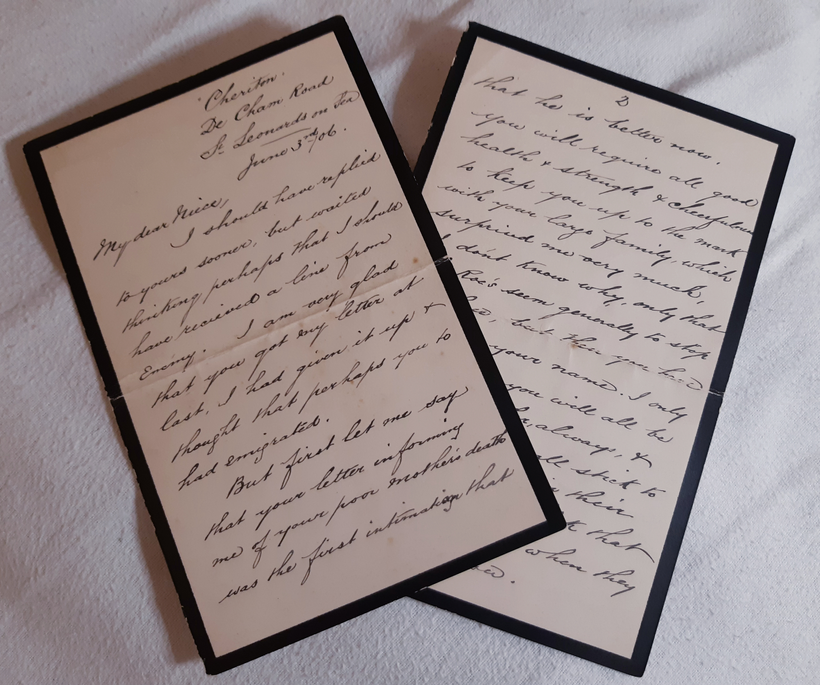

Due to the rarity of caul births, many cultures latched onto the image of the veiled baby and began to view cauls as possessing extra significance or other-worldly powers. Subsequently, cauls were frequently preserved – predominantly by drying and attaching said membrane to a piece of paper, or similar flat surface. Through preserving them, they could be kept upon one’s person for a variety of positive or healing properties.

There are varying worldwide examples of superstitions attached to a birth caul, for example;

Roman midwives were known to have taken cauls and sold them at high prices to lawyers as a talisman to aid them in legal victory. In Croatia (supposedly Dalmatia, in particular) cauls were sometimes placed under the pillow of a dying person with the belief that such an act would soothe their passing. In Belgium, it was believed that if the caul was buried in a field, the child would have a long and lucky life, they were also used in potion making in a variety of cultures, mostly for curing diseases such as malaria.

Not all preserved birth cauls are presented like my own – my flimsy object d’art is adhered to a piece of paper, which seems to have been the norm for most preserved cauls (from what I’ve seen within the UK). To preserve one in such a manner is incredibly easy, with the midwife requiring to do little other than press a piece of paper across the baby’s face; the caul would then adhere to it and your fibrous keepsake would be removed intact.

However, there are some excellent examples of creative caul presentation. The Pitt Rivers museum in Oxford has in its collection a glass rolling pin from 1855 which once contained a child’s caul. Despite its decidedly domestic purpose, it too was used by a sailor and is decorated with scenes of ships under full sail. A more delicate method of preservation can be found in London’s Victoria and Albert museum. Within its current, displayed collection is a small gold locket with engraving from 1597. Within the heart-shaped locket lies part of the caul of John Monson, who most probably received the trinket as a baptismal gift. This is not to say that Elizabethan baptism gifts were exclusively restricted to bits of desiccated tissue (as delightful as that image may be), as spoons, cups and things made from precious metals were most common.

In the UK, as with many other European countries, the caul is most associated with sailors. It has been a long-standing maritime superstition that to be in possession of a baby’s caul is to protect oneself from drowning. Understandably, due to the scarcity of such objects, sailors for centuries have been paying extortionate amounts for cauls, carrying them as added protection on voyages. A sailor, as recorded in Henderson’s ‘Folk-Lore of the Northern Counties’, paid fifteen pounds in the 19th century for a caul which he then kept as a talisman for thirty years.

In literature, Dicken’s David Copperfield features a scene where David’s own caul is auctioned – with the character noting that he ‘felt quite uncomfortable and confused, at part of myself being disposed of in that way’ with the caul being purchased by an old woman who ‘never drowned, but dies, triumphantly in bed, at ninety-two’.

Despite our modern ambivalence to the whereabouts of a partial amniotic sac, there remains a small group of people who interpret their own caul births as a sign of their special-ness. This (predominantly online) community collectively refer to themselves as ‘Caulbearers’. This community often see themselves as overly empathetic with the ‘sensation of precognition’ and potentially in possession of an array of (predominantly wet) supernatural abilities; such as the ability to find underground water supplies, predict weather changes, anticipate bountiful catches/harvests etc. Additionally, Caulbearer.org makes the claim that ‘The purpose of the caulbearer is to serve mankind, and to guide men and women to understand themselves and the world and universe within which we live.’

Cauls understandably became less prized as the mechanics of birth become less mysterious, however their curious nature still prompts occasional interest. Primarily through nifty lists of famous faces that were once covered by a membrane –

So, I’ll leave you with the fun fact that Napoleon, Liberace, Lord Byron and Sigmund Freud were all ‘caulbearers’, and none of them died by drowning. Coincidence?

(Yes).

Further reading:

http://england.prm.ox.ac.uk/englishness-sailors-charm.html

https://www.babymed.com/labor-delivery/en-caul-baby-birth

https://www.popsugar.com/moms/Photos-Babies-Born-En-Caul-41499029

Leave a comment