To many city workers, Bunhill Fields is just another thoroughfare. A place to sit during your lunchbreak, or a handy shortcut across Islington. At all hours of the day, the central paths are packed with power-walking bankers, suited office workers and exhausted couriers. For such a busy place, it holds little interest for most, and stopping to examine the odd grave is sure to incite quizzical looks from passers-by. The normality and mundanity of Bunhill Fields is understandable; seeing a location so often would stop anyone from looking outside its functionality.

Bunhill Fields is a relic of London’s overcrowded inner-city burial grounds. It may seem unremarkable from the gateway, but is in fact a Grade I listed site on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens. What remains of the once-large site is a mere 4 acres that is preserved and tended as a public and community garden maintained by volunteers, Friends of the City Gardens and the City of London Corporation. During my last visit, gardening volunteers were wrapped up, planting bulbs for spring by digging between the graves – which made for a strange viewing experience as a visitor. Feeling so many eyes on me, it seemed that even the volunteers were baffled by my interest in the interred.

Long closed to new burials, Bunhill Fields was used as a place of rest from 1665 until 1854, taking on an approximated 123,000 burials. Today, nothing close to that number of visible burials remain. In the small, extant area, and between areas of paving, utility buildings and open spaces, around 2000 memorials are visible at the site today. Most of these visible graves are crammed into dense areas, enclosed with a wrought iron fence, with gates only opened by keyholders. While this has surely resulted in the preservation of many of the memorials, as a taphophile or grave-botherer, it makes for a frustrating experience – wanting to get closer, but having to satisfy yourself with a phone camera and zoom function.

Bunhill Fields was an unusual site for several reasons. It was an experimental burial ground of sorts. Before the Burial Acts of 1857 (there were several acts from 1852-85, legal fans) which regulated burial and encouraged the creation of large, non-denominational cemeteries to ease the overcrowding of churchyards, there were few options for non-denominational burials. The burial of nonconformists was a particular issue for many counties and regions, where burial sites (Anglican, Catholic etc.) had strict faith requirements in order to be buried in their consecrated grounds. Those whose faith was still Christian, but did not adhere to established Church of England doctrine had few options of where to spend eternity, especially if their local churchyard was bursting at the seams with dead parishioners.

The term nonconformist emerged in England around 1660, following the restoration of the Stewart Monarchy with King Charles II. By the 19th century it was used in conjunction with many sects and denominations, but most notably, Quakers, Baptists, Puritans, Brethren and Methodists. Bunhill Fields is a stone’s throw from the birthplace of Methodism and the museum of John Wesley (the movement’s founder), so it is little wonder that many famous Methodists and Methodist Ministers can be found in the Islington thoroughfare. Similarly, there are many Quaker sites nearby, such as a former burial ground by Bunhill Row. This site was open from 1661-1855 and holds the remains of George Fox (d.1691), a founder of the Quakers. Much like Bunhill Fields, it is now preserved as a public garden, under the care of the London Borough of Islington.

But before we look at Bunhill Fields’ most famous residents, a note on squirrels. The burial ground is one of few green spaces in the borough and so thrives as an oasis for grey squirrels and urban wildlife. With so many commuters leaving crumbs of their lunches behind and passing through the site every day, the furry beasties are emboldened to say the least. Their familiarity with humans is striking, as they comfortably approach walkers for snacks and attention, encouraged by the occasional visitor with a fist full of seeds. However, as pleasant as a Snow White fantasy seems, the horror stories of vicious squirrels are endless. Whether they jump from trees of scuttle up your legs, be wary. One Tripadvisor review summarises Bunhill Fields’ wildlife perfectly; ‘Squirrels. Like tonnes of them. Super cute. Super aggressive.’

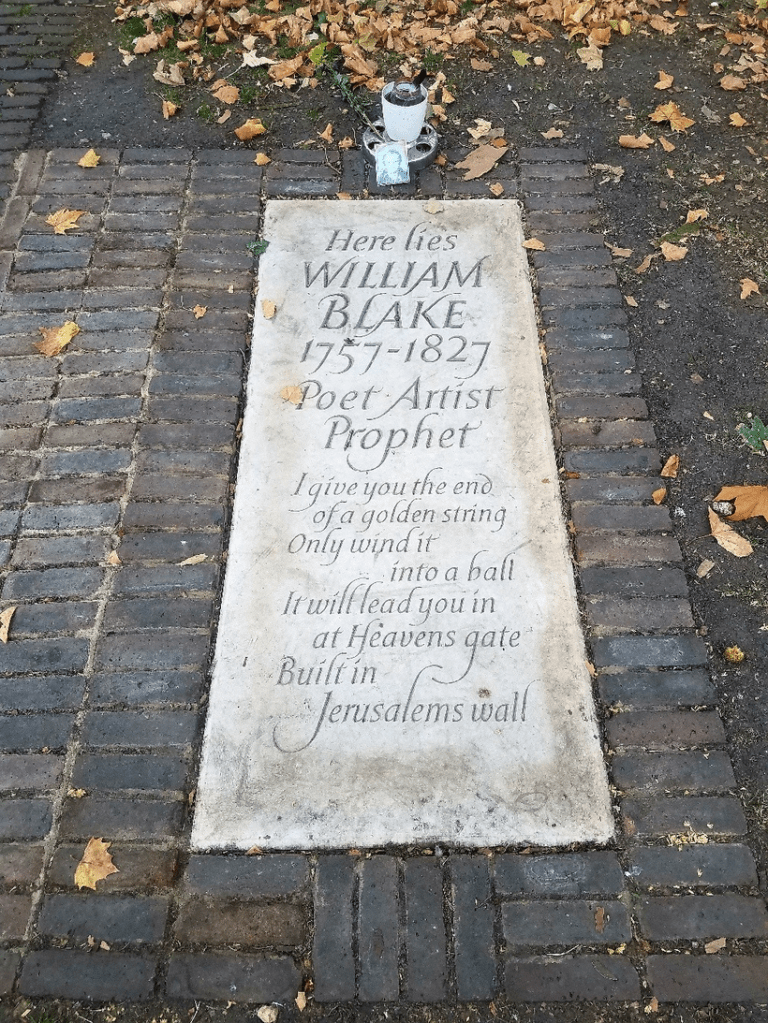

Bunhill Fields most famous resident is probably the artist and poet William Blake. For many years, there was one singular memorial to Blake and his wife Catherine Sofia, stating that their remains lay ‘nearby’. However, thanks to the detective work of two Blake afficionados, Carol and Luis Garrido, the exact resting place of William and Catherine was pinpointed in 2018. It took two years of trawling through burial records to be sure, but the Blake Society were finally able to commemorate the poet’s life with an accurate grave marker.

Like so many artists, Blake was largely unknown when he died in 1827 and was buried in a communal grave, being the fifth of eight coffins.

There had been a marker for centuries, until damage obtained during WWII caused the Corporation of London to remove many memorial remnants and clear a part of the site for use as gardens. Blake’s memorial was moved to a different section, set beside an obelisk commemorating fellow writer, Daniel Defoe. Thankfully, the original records remained, which showed that the plots had been arranged in a grid and the original resting place could be found. There are few individuals who can boast a two memorials in the same burial site, and Blake joins such iconic contemporaries as Edgar Allan Poe who also has two memorials in one graveyard.

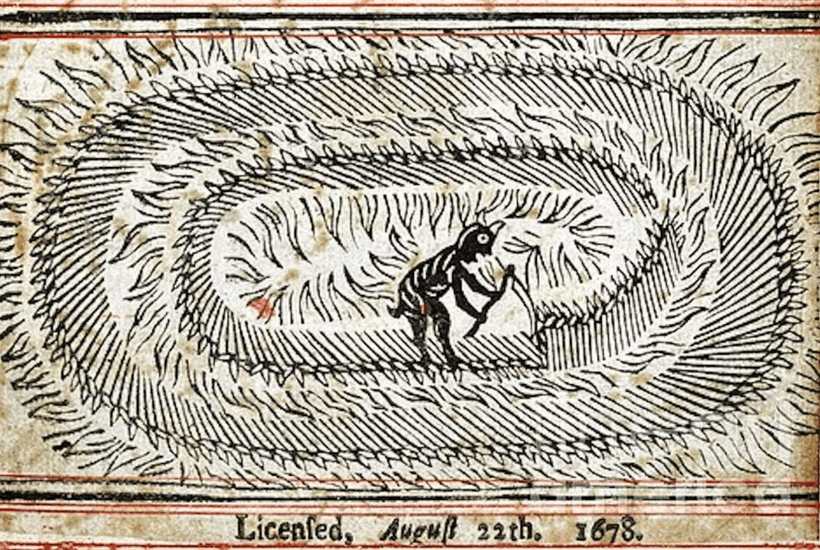

John Bunyan’s grand memorial is hard to miss, being a huge tomb, topped with an effigy of the writer. A prolific author and nonconformist preacher, he is one of Bunhill Field’s most recognisable residents, despite being frequently covered in squirrels and pigeons. Born in 1628, his work ‘The Pilgrim’s Progress’ was a long-standing labour of love, and a controversial creation at the time, despite being religious, as it was a work of fiction. In the years between its publication and Bunyan’s death in 1688, The Pilgrim’s Progress had thirteen published editions and is believed to be the second-most read Christian text, next to the Bible.

Daniel Defoe’s obelisk is one of the most imposing and central memorials at Bunhill Fields. Upon his death in 1731, The Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders author had no public memorial, dying in relative obscurity, much like Blake. It’s presumed that Defoe was also hiding from his creditors at the end of his life, so obscurity offered something of a safety blanket. It is a rumour oft-repeated that he was buried under the surname of Dabow, thanks to a clerical error on the part of the gravedigger, but like so much of his burial history, we can never be sure.

The current memorial may not mark his actual grave as once again, war damage resulted in the upheaval of many parts of the cemetery. However, due to the rising Victorian adoration of Defoe’s work, a sculpture to commemorate the great writer was funded nearly 150 years later in 1870. The children’s magazine Christian World was successful in its efforts and through the aid of 1700 contributors, raised £150 for a lasting grave marker to be erected.

There are many other graves and interments worth noting, particularly theologians, ministers and religious educators such as Susanna Wesley (the ‘Mother of Methodism’), Isaac Watts and John Gill.

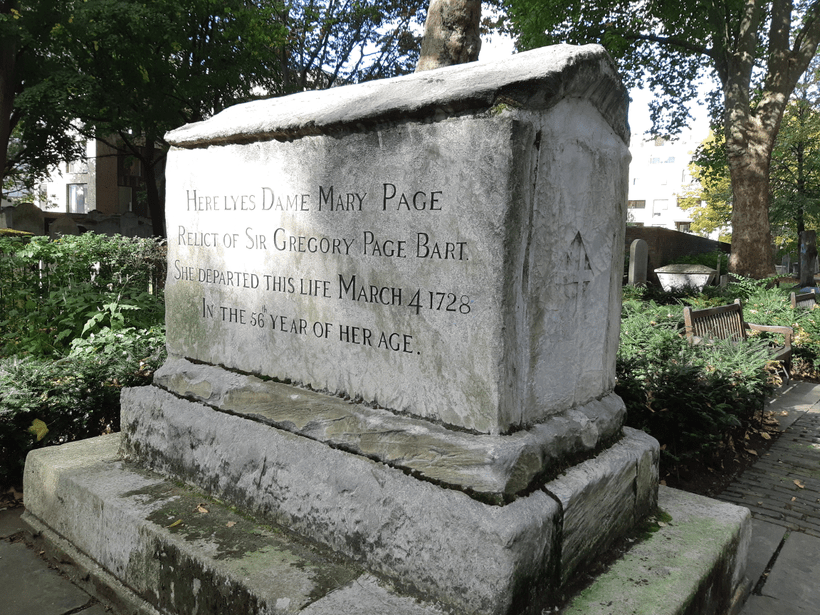

However, the final grave of interest is to a woman rarely discussed outside of her strange epitaph. Mary Page was the wife of wealthy merchant, MP and shipwright Sir Gregory Page who made his substantial fortune in the East India Trade. Born into privilege (inheriting his father’s brewery as a young man), he worked his way up the ranks, eventually becoming a director of the East India Company. He died in 1720 and left an enormous fortune of over £800,000, with the greatest sum (estimated at £700k) going to his eldest son. Mary and their three other children shared the remainder, which would have kept her in comfort until her own death, eight years later.

Dame Mary Page rests beneath an enormous chest tomb with simple and clear wording to each side.

Here Lyes DAME MARY PAGE,

Relict of Sir Gregory Page, Bart.

She departed this life March 4 1728,

in the 56th year of her age.

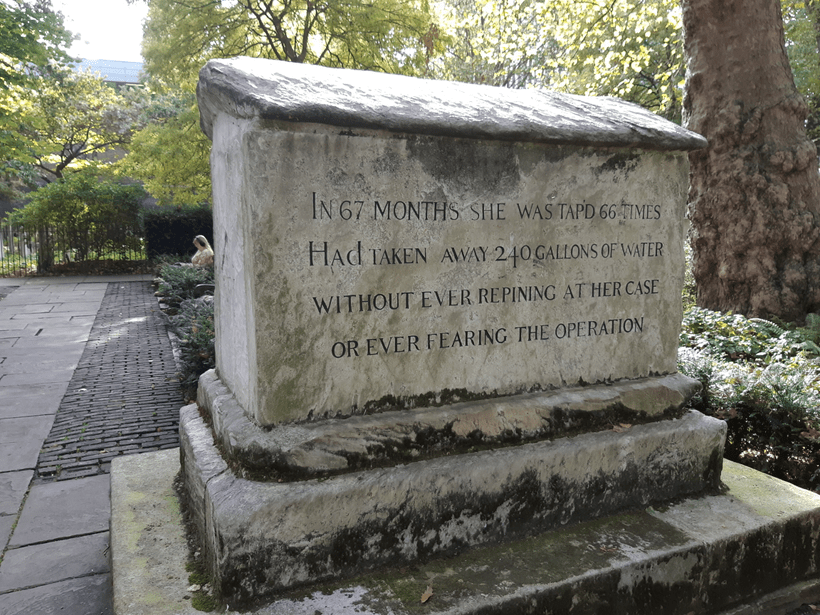

And on the other side of the tomb:

In 67 months she was tap’d 66 times

had taken away 240 gallons of water

without ever repining at her case

or ever fearing the operation.

Unsurprisingly, ‘water’ doesn’t refer to H2O, but ‘extra-cellular fluid’. During her long illness, doctors removed over 1000 litres from her, believing that removing the liquid would remove the illness. However, to contemporary medical professionals, her ailments align more to a case of dropsy, where the area under the skin fills with fluid. Today, this is commonly called edema, or oedema, depending on your spelling and mainly occurs in the feet, ankles and legs. Other historians believe that she suffered from the first recorded case of Meigs syndrome, which presents as a trio of afflictions; ovarian tumours, ascites (fluid in the abdomen) and pleural effusion (fluid between the lungs and the chest wall). The suffering that Mary endured can only be imagined, and I always find it so curious that such grand and rich lives can be commemorated by a rather grizzly nod to their disease.

While Bunhill Fields is often overlooked by grave tourists who are lured by the bright lights of the capital’s ‘Magnificent 7’ Victorian garden cemeteries, the cramped and strange little site is well worth the trip. Not only does it celebrate some great writers, but is a glimpse into a burial ground of yesteryear, the type of which rarely remains today. Not all graveyards need mausoleums to be wonderful; others just need the common man and an army of squirrels.

***

Liked this post? Then why not join the Patreon clubhouse? From as little as £1 a month, you’ll get access to tonnes of exclusive content and a huge archive of articles, videos and podcasts!

Pop on over, support my work, have a chat and let me show you my skulls…

www.patreon.com/burialsandbeyond

Liked this and want to buy me a coffee? To tip me £3 and help me out with hosting, click the link below!

https://ko-fi.com/burialsandbeyond

***

References/Further Reading:

https://foursquare.com/v/bunhill-fields/4b586e43f964a5205f5728e3

http://thelondondead.blogspot.com/2015/02/tapped-60-times-of-240-gallons-of-water.html

https://cemeteryclub.wordpress.com/2014/01/23/the-bone-hill/ [Excellent resource, as ever]

Leave a comment