As cartoon witches wiggle their wands above bubbling potions and stage magicians command a rabbit to leap from a hat, we’re all used to ‘Hocus Pocus’ as a term used to command magic and mysterious forces. But where on earth did this phrase come from?

No, the phrase wasn’t invented by Disney in their 1993 Halloween classic, but rudimentary internet searches offer just as little insight. An often-repeated myth is that ‘Hocus Pocus’ is a deliberate bastardisation of the Latin Mass sacramental blessing, ‘Hoc est corpus meum’, meaning ‘This is my body’. This suggestion placed conjurers, magicians and jugglers as deliberately anti-church, anti-establishment and anti-God. Much like the satanic panic of the 1970s and 80s, society needs a common enemy, and while American courtrooms had baffled rock stars, some 17th century priests also steered their blasphemy concerns towards the world of entertainment. However, the first individual to make this comparison and speculate on this etymological origin was the prelate and Archbishop of Canterbury John Tillotson (1630-1694). While he may have believed in his own speculations, he appears to be the only person of standing to make such an assertion, provided no evidence and spoke about a term that had been established for centuries before.

Tillotson proposed that the garbled form of holy liturgy allowed for the phrase to become a dark incantation, functioning as a means to confuse and repress the consciousness of the conjurer’s audience, allowing his ungodly tricks to baffle them. The following quote is attributed to him, with the sentiment ultimately mirrored in his sermons, but does not appear to be his own words, according to the primary text.

“I will speak of one man … that went about in King James his time … who called himself, the Kings Majesties most excellent Hocus Pocus, and so was called, because that at the playing of every Trick, he used to say, Hocus pocus, tontus tabantus, vade celeriter jubeo, a dark composure of words, to blinde the eyes of the beholders, to make his Trick pass the more currantly without discovery.”

While this isn’t any great condemnation of the art of conjuring (often referred to as juggling/jugglers during this period), it presents an example of the larger garbled, pseudo-latin phrases used by performance magicians in the 17th century. Over time, our use of Hocus Pocus as a command, may well have been streamlined.

This quotation is often presented separated from its context and authorial purpose, which does disservice to the historical importance of the wider work, but also skews popular history and allows half-truths to travel.

Thomas Ady’s ‘A Candle in the Dark: Shewing The Divine Cause of the distractions of the whole Nation of England, and of the Christian World’ was published in 1655 and was a safety manual of sorts for clergymen, to educate themselves about established unchristian or pagan behaviours, but also the folk beliefs of ‘poor people’, as having such knowledge would be profitable before they ‘passe the sentence of Condemnation against poor People, who are accused for Witchcraft’[1]. The work condemns witch trials and brutality towards the working classes under the misguided banner of scripture, but guides the reader towards what are acts of God, rather than acts of witchcraft. It also highlights what areas could be of genuine concern. Indeed, the intention of being ‘a candle in the dark’, illuminating a path of knowledge, rather than persecution, was a noble one, and one much needed by a country once-ravaged by supernatural hysteria. Through intellectual understandings of theological history, he presents the errors and changing meaning of language in Biblical translations, attacking the precedent of witchcraft persecutions set in the years and centuries before.

In the introduction to ‘A Candle in the Dark’, Ady writes his clear purpose in a condemnation of contemporaneous ‘witch’ executions:

‘The Grand Errour [sic] of these latter Ages is ascribing power to Witches, and by foolish imagination of men’s brains, without grounds in the Scriptures, wrongful killing of the innocent under the name of Witches…Witches are not such as are commonly executed for Witches.’[2]

He goes on to question the lack of scripture underlying the former checklist of traits used in the search for witches. However, throughout the work, he does not condemn the idea of malicious witchcraft and sorcery, but argues for a more stringent identification process. However, ‘A Candle in the Dark’ is not an impartial work, as Ady condemns Catholicism throughout and attributes the Civil War to divine vengeance, punishing England for it part in the persecution of so-called witches.

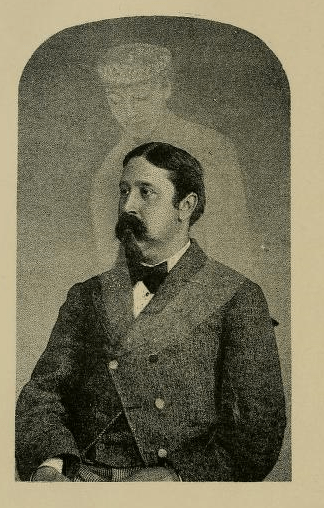

John Tillotson (1630-1694) by Charles Beale (1660-1714). Via the Royal Collection Trust.

John Tillotson’s mention of ‘Hocus Pocus’ appears following an argument as to the nefarious deceitful activities of jugglers. Jugglers (used as a broad term) are presented as more than a public nuisance, but as sometime criminals and a threat to social wellbeing.

He recounts a ‘juggler’ ‘who called himself, The Kings Majesties most excellent Hocus Pocus, and so was he called, because that at the playing of every Trick, he used to say, Hocus pocus, tontus talontus, vade celeriter jubeo, a dark composure of words, to blinde the eyes of the beholders, to make his Trick pass the more currantly without discovery, because when the eye and the ear of the beholder are both earnestly busied, the Trick is not so easily discovered, nor the Imposture discerned.’ Furthering this argument, parables such as that of the Samaritan are presented, where communities believed in the tricks of conjurers like they were Gods, until they personally experienced true godly miracles (such as turning rivers to blood in Exodus).

While I cannot find this exact (frequently circulated and popular quote) in the original 1655 text of A Candle in the Dark, one of the earliest internet mentions of Tillotson’s argument is from the now-archived site, the Maven’s Word of the Day .[3] Here (posted 7/10/99) they quote the former archbishop as saying :

“In all probability these common juggling words of hocus pocus are nothing else but a corruption of ‘hoc est corpus’, by way of ridiculous imitation of the priests of the Church of Rome in their trick of Transubstantiation.”

While this is one of the earliest written records of ‘Hocus Pocus’ used as a conjuring term, it is aligned with Christian liturgy and doctrine by context alone, and does not, convincingly or otherwise, present the idea that the phrase was a deliberate corruption of the blessing, ‘Hoc est corpus meum’. While it is also aligned with ‘A Candle in the Dark’ due to the subject matter, this particular quotation seems to be from a singular sermon of the Archbishop[4], rather than a widely-accepted theory, let alone a theory confirmed and printed within A Candle in the Dark.

Also, considering that the work from which these words were reportedly taken was decidedly anti-Catholic in tone, it would be useful for a phrase so associated with conjurers and falsehoods to be aligned with the act of transubstantiation. However, we must also be aware of the adverb, probably. A likelihood, not a certainty, and shouldn’t really be presented as a clear etymological root.

This exact quote appears in far later, 19th century texts (without references), such as ‘The Etymological Compendium by William Pulleyn (3rd Edition, pub William Tegg and co. 1853) and ‘A Lift for the Lazy’ by I. Wharton Griffiths (Ed. George P. Putnam, New York, 1849), but finding these words in anything before the 19th century has proven particularly difficult, nigh impossible.

via the University of Glasgow Library.

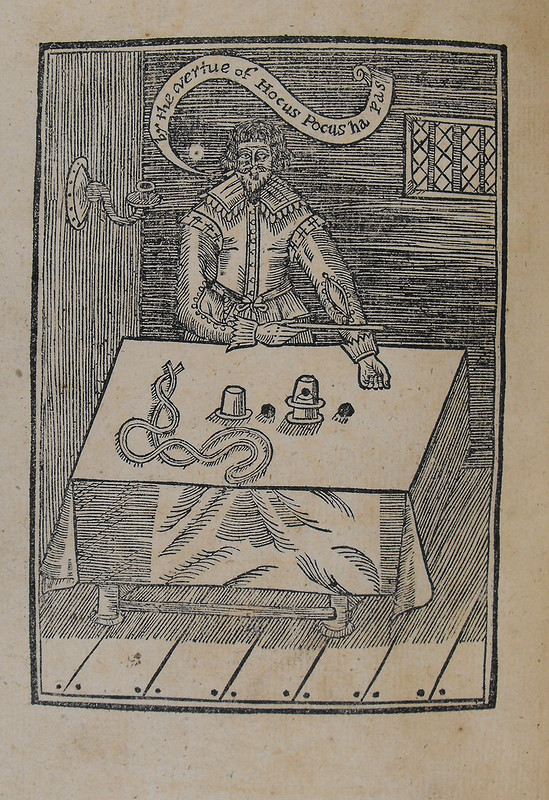

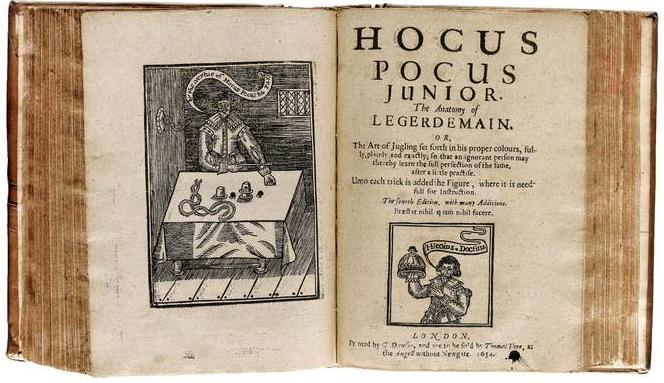

Throughout the 17th century, and long before the publication of Ady’s work, Hocus Pocus was a popular moniker for conjurers, magicians and jugglers. The earliest English-language work on magic and sleight of hand (then known as ‘legerdemain’) was published in 1635 as ‘Hocus Pocus Junior: The Anatomie of Legerdemain’. This anonymously authored pamphlet is a how-to book for magic tricks, featuring several ball and cup tricks, how to modify a knife (‘How to seeme to cut ones nose halfe off’), how to add a lock to your mouth and several larger-scale tricks such as beheading a man (‘it is called the decollation of John Baptist’[5]).

However the phrase ‘Hocus Pocus’ predates this still, as the work suggests that the title was taken from the stage name of a successful contemporaneous magician. One popular theory as to the identity of the original Mr Hocus Pocus, is that of William Vincent, a magician who gained a licence to perform magic in 1619[6]. Vincent and his accompanying troupe would also go on to gain two royal patents, and tour the country to great success, with some of these early playbills still in the possession of the British Library. According to John H. Astington of the University of Toronto:

‘A phrase from his juggler’s patter became his signature stage title and passed into subsequent English usage as “hocus pocus” to mean both trickery and verbal obscurantism, much employed in the later seventeenth century in works of religious polemic.’[7]

Vincent was predominantly a solo performer of sleight of hand tricks and juggling. These similarities between Vincent’s act and the Hocus Pocus pamphlet lead many scholars to believe that he was the author of the work, chronicling his act in several parts. In Astington’s journal article, while Vincent would ultimately train a troupe in a variety of magic and circus feats, ‘The Hocus Pocus appearances were one-man shows, without much demand on space: a table and an open area for observers in front of it were all Vincent probably needed.’[8]For any would-be performer wanting to impress their audiences, avoiding trading under another’s name, but incorporating the ‘Hocus Pocus’ name as a familiar phrase in their own patter would be a means of establishing their act, physically and tonally.

The paper-trail of Vincent exists in ledgers, newspapers and playbills, rather than interviews as to the reasons for his stage name. Vincent himself had played a previous comedic role as ‘Jack Pudding’, and understood the name for a meaningful, recognisable stage name. Therefore, the argument that Hocus Pocus is a combination of nonsense words, rather than a modified existing Latin phrase, is a far stronger one. Arguably, the phrase sounds like it possessed Latinate roots, but is more likely to be a form of amusing dog Latin[9], as the rhythm and perceived tone of the phrase could be of more importance and relevant in the field of entertainment than pursuing any subversive, convoluted, anti-Catholic sentiment. However, during this period in English history, anti-Catholic sentiment was rife across England (changing from the state religion, to outlawed in just a few decades), with the Catholic church’s rituals, vestments and relics seen as both satanic and dangerous. Catholics could be seen as traitors and potential threats to the monarch, and mimicking the concluding words of Catholic mass as though they were a conjuring trick, the speaker would be aligning transubstantiation with juggling and deception.

Yet looking further back in print, the Hocus Pocus (both hyphenated and separate) phrase appears to predate its most famous namesake, and the 17th century itself.

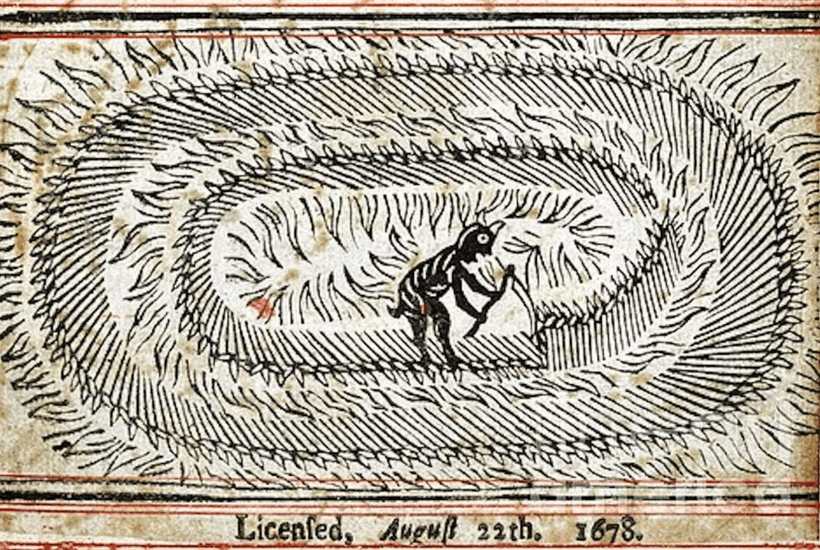

via Historically Speaking

The Historically Speaking website, when writing on idioms, presented a 1590 German translation of The Taming of the Shrew, where ‘Hocus Pocus’ was included as a reference to magic incantations[10]. This would take the common man’s understanding and usage of the phrase, both in Germany and England to far earlier, potentially into the mid-16th century, if not earlier.

Historian Sharon Turner wrote in ‘The History of the Anglo-Saxons’ (written between 1799-1805) that the term Hocus Pocus may derive from the Norse magician ‘Ochus Bochus’, a demon of the north. According to Turner, ‘It is probably that we here see the origin of hocus pocus, and Old Nick’[11] These auditory similarities between Ochus Bochus/Hocus Pocus could add further credence to the theory that the popular phrase was little more than nonsense words, created by the common man for no other reason that the love of rhyme. Similarly, the word ‘hoax’ is often cited as developing from the word ‘Hocus’[12], due to their similar sound and context used. However, as intuitive as this link may seem, there are no clear links between the two.

While the root of our favourite magician’s command may not have a convenient and clear history, it seems rather fitting tale for a term used to confound and deceive.

Next week, a 6000 word paper on the etymological origins of ‘Izzy wizzy, let’s get busy…’

***

Liked this post? Then why not join the Patreon clubhouse? From as little as £1 a month, you’ll get access to tonnes of exclusive content and a huge archive of articles, videos and podcasts!

Pop on over, support my work, have a chat and let me show you my skulls…

www.patreon.com/burialsandbeyond

Liked this and want to buy me a coffee? To tip me £3 and help me out with hosting, click the link below!

https://ko-fi.com/burialsandbeyond

***

Sources/References and Footnotes:

https://www.etymonline.com/word/hocus-pocus

http://www.hocuspocusjr.com/hocvspocvsjr.htm

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/34375/34375-h/34375-h.htm

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/34375/34375-h/34375-h.htm

[1]https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A26476.0001.001/1:1?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

[2]https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A26476.0001.001/1:2?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

[3]https://web.archive.org/web/20080905211827/www.randomhouse.com/wotd/index.pperl?date=19991007

[4] After skimming collections of his sermons, I have not yet found the original source of this quotation.

[5]https://www.gutenberg.org/files/34375/34375-h/34375-h.htm

[6] The licence stated that he had the freedom ‘to exercise the art of Legerdemaine in any Townes within the Relme of England & Ireland’.

[7] William Vincent and His Performance Troupe 1619-1649. Astington, John H. Renaissance Drama Journal, Vol 46, No. 2, 2018. University of Chicago Press.

[8] William Vincent and His Performance Troupe 1619-1649. Astington, John H. Renaissance Drama Journal, Vol 46, No. 2, 2018. University of Chicago Press.

[9] A humorous device whereby one pretends to translate words into Latin by conjugating or declining them as though they were Latin.

[10]https://idiomation.wordpress.com/2015/06/04/hocus-pocus/

[11]https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=AP9azWe4l74C&dq=ochus+bochus+sharon+turner&pg=PA17&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=ochus%20bochus%20sharon%20turner&f=false

[12] According to https://www.phrases.org.uk/meanings/hocus-pocus.html ‘hoax’ was first used in 1796.

Leave a comment