Today we’re taking a trip to old London town to check in with St Bartholomew the Great, London’s oldest surviving church.

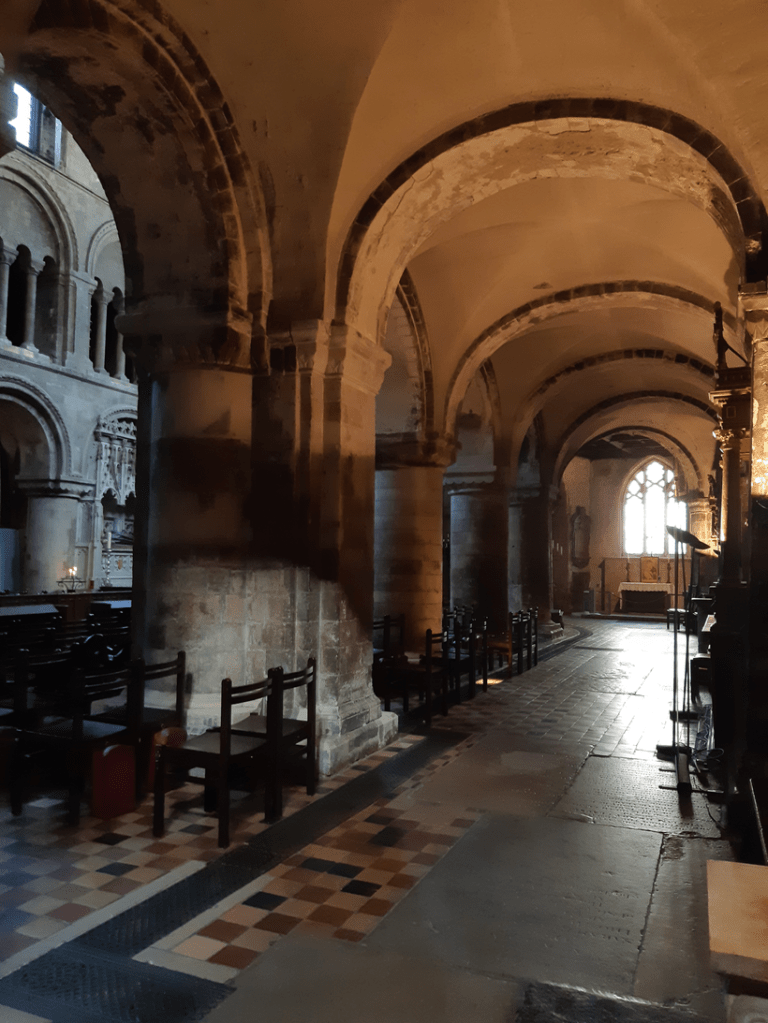

While St Bartholemew’s is a pretty hefty building, it’s easy to miss the narrow entrance among the hustle and bustle of Smithfield commuters. Peeking through the archway of a Tudor building, the distant checkerboard brickwork of St Bartholomew’s peeks through like the tell-tale sign of a medieval Ska Band.

St Bartholomew was founded in 1123 by Rahere (just the one name, like Beyonce…), a courtier of King Henry I. It’s believed that Rahere was greatly affected by the deaths of the king’s wife and children and had a revelation regarding his own life’s purpose. Undertaking a pilgrimage to Rome, Rahere fell seriously ill and desperately prayed to God for his life to be saved, promising grand acts should he survive. He promised to build a hospital for the poor in London upon his return, and he came good on his vow. He recounted that upon his return journey home, the vision of St Bartholomew appeared to him, saying

“I am Bartholomew who have come to help thee in thy straights. I have chosen a spot in a suburb of London at Smithfield where, in my name, thou shalt found a church.”

St Bartholomew is a very visceral saint to behold, as demonstrated in centuries’ worth of artistic renderings of his corpse. However, in life, he is believed to have taken Christianity to Armenia. Like most biblical figures, this didn’t go down terribly well with everyone and he was flayed alive, before being crucified upside down. In art, he is often depicted with his skin draped over his arm, like some horrific, fleshy dinner jacket. Of course, he is also celebrated for his martyrdom, and the brutal nature of his death, all because of his religious devotion and belief in the gospel.

Rahere went on to found not only a hospital, but an Augustinian priory (where he served as prior) and a church (where he served as master), truly laying down charitable roots in the city, much of which remain today.

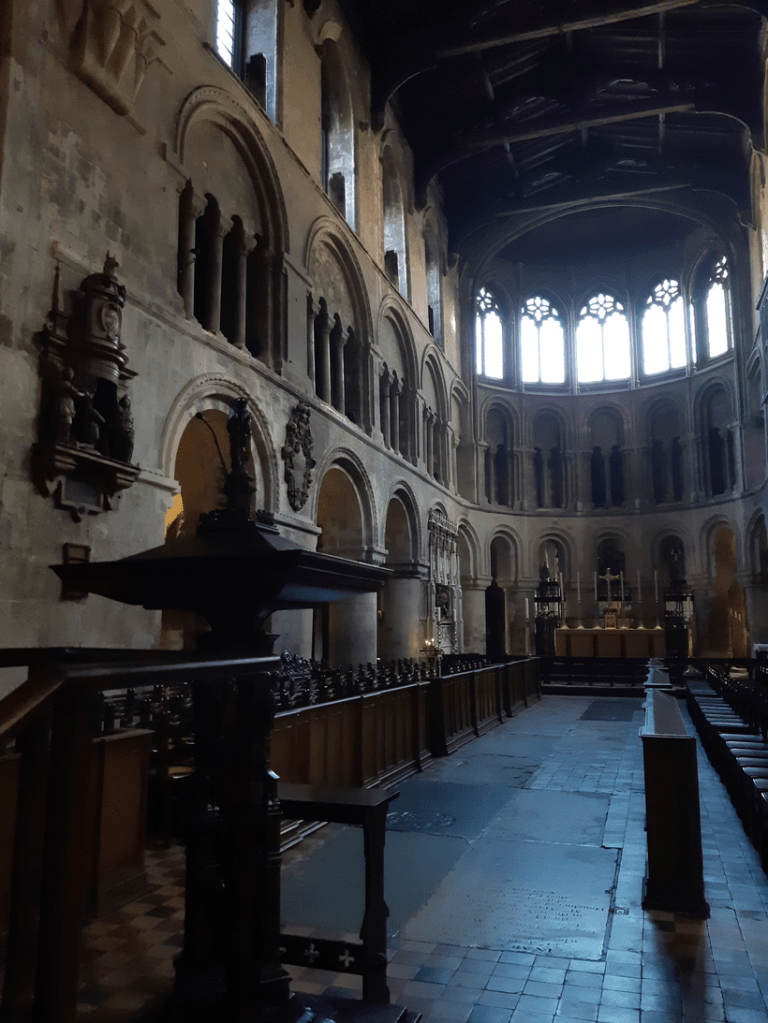

The priory lasted until 1539, when Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries resulted in the closure and surrender of St Bartholomew’s. While the church nave was demolished, parts of the priory buildings survived the wrecking ball of industry and were restored in the 19th century, as the Victorians sought to preserve what remained of the church.

St Bartholemew’s is a working church and a tourist draw in equal measure. Indeed, when I was there for a spot of touristing and quiet reflection in the riotous city, the echoes of traffic were soon replaced with the echoes of 75-year-old Brenda who can only read information boards out loud, and not in her head… Nonetheless, it makes for a really lovely visit. If ecclesiastical history isn’t of great interest, St Bartholomew’s role in several high-profile films may entertain the disinterested visitor –Four Weddings and a Funeral, Avengers: Age of Ultron, Shakespeare in Love, Sherlock Holmes and the greatest film of all time – Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (I say this unironically, I adore that film to a frightening degree) all featured the church as a dramatic location.

One of my personal, and very modern highlights, is the golden sculpture of St Bartholemew, ‘Exquisite Pain’ by Damien Hirst. Whatever your views on bisected cows may be, Hirst is one of my personal favourite artists, and his St Bartholomew sculptures are so arresting and unsettling, he brings the brutality of martyrdom and traditional saint imagery into the contemporary gaze.

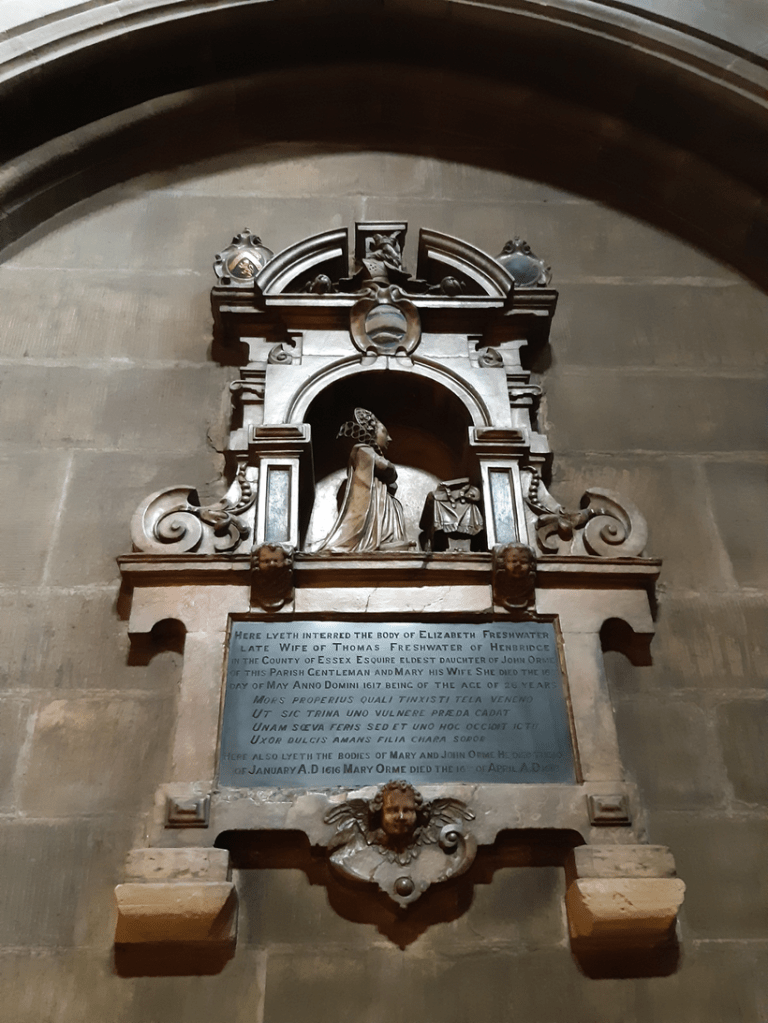

The age of St Bartholemew’s affords it a staggering cross-section of memorial plaques, commemorating the great and good of centuries’ past. The beautifully preserved memorial to Elizabeth Freshwater (c1617) depicts her knelt beside a prayer desk, commemorating her devotion into eternity. Her memorial is also regarded as one of the earliest examples of the baroque in England, and of great historical importance. She married twice, both times to London lawyers, before dying aged 26.

The tomb of St Walter Mildmay is one of the grander graves in St Bartholemew’s, adorned with some of the most intricate masonry, remarkably preserved so many centuries later. Sir Walter Mildmay was an eminent politician who somehow managed to survive the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth I – quite the feat for anyone of status. He commissioned the dramatic altar tomb for his wife (d.1576), with a view to joining her, which he did several years later in 1589.

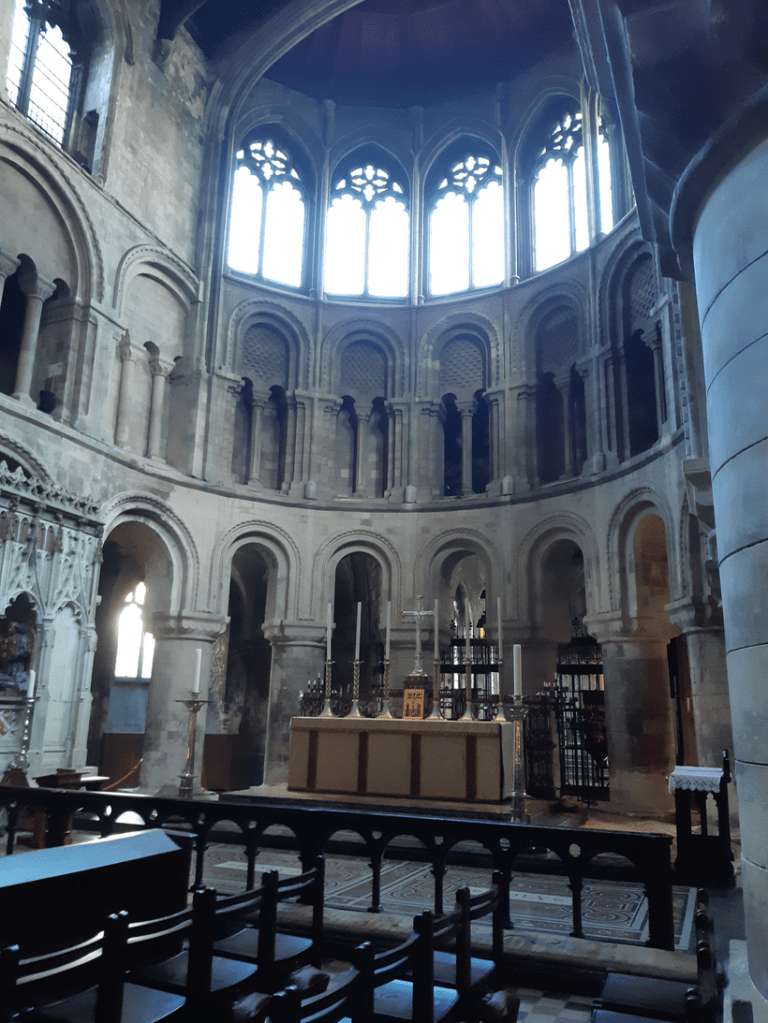

Standing in the sanctuary of the church, looking towards the altar is an almost overwhelming experience. The great height, staggered archways and memorials represent centuries of lives, beliefs and stages of London’s development, most of which are completely wiped from the city just outside its doors. And I’m sure many more profound thoughts would have followed if I hadn’t been thinking ‘this is where Maid Marian gave alms to the poor… this is where the Sheriff of Nottingham sat…’.

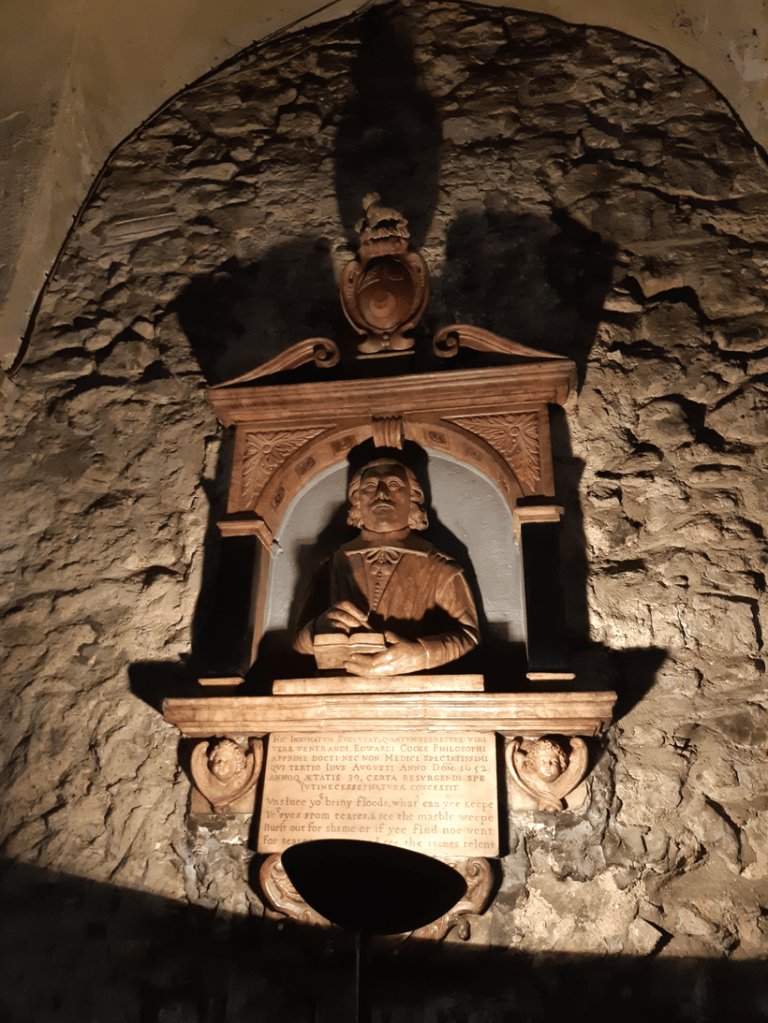

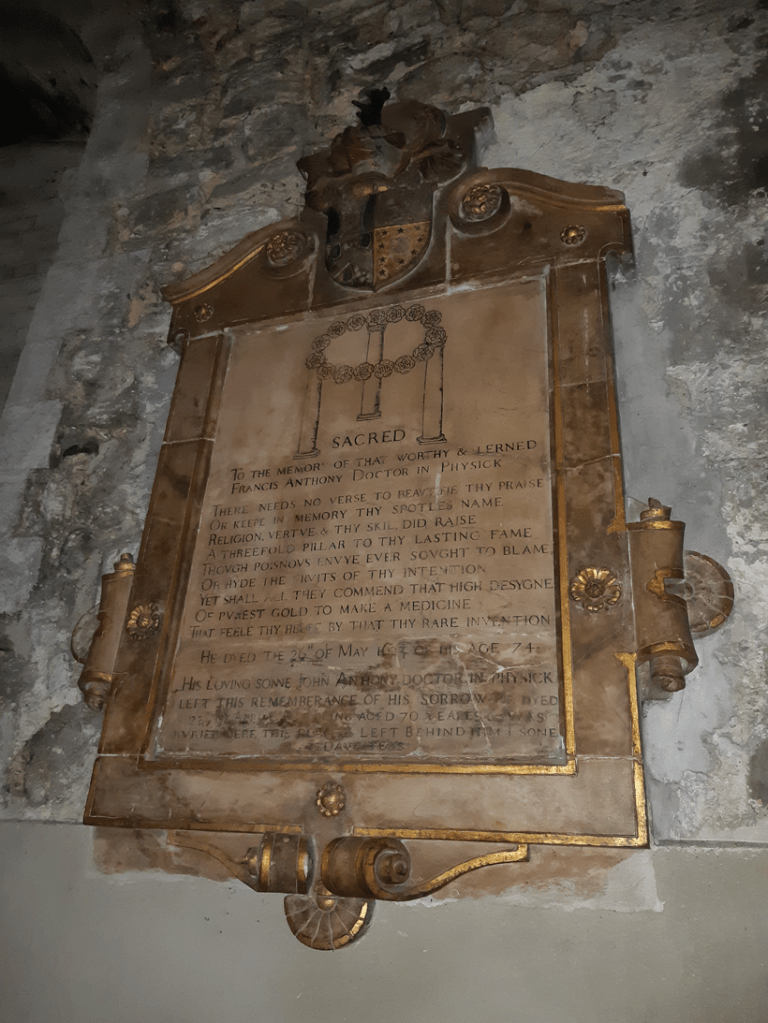

Other notable memorials include that of Edward Cooke (c1652) that was once renowned and feared for its strange ability to weep. While supernatural and religious explanations were commonplace, in more terrestrial terms, the water vapour of the humid church building would be absorbed into the porous marble, which in turn would occasionally transform into ‘tears’. Sadly, once the Victorians decided to install a radiator nearby, the miracle tears stopped.[1]

The memorial to James Rivers is of remarkably similar design, but sadly does not appear to weep or even sniff. Poor effort, mate.

The Lady Chapel holds an additional strange history, being the place where Benjamin Franklin ‘learned his trade.’ Following the Reformation, the Lady Chapel was separated from the church and used as commercial premises for hire, before the church repurchased the chapel in 1897. In the 18th century, this space was occupied by a printer’s workshop which would employ – American polymath and founding father – Benjamin Franklin as an apprentice.

And finally, Rahere himself. The remains of Rahere are interred within a tomb at St Bartholemews, where he spends eternity beneath an effigy of himself. Rebuilt in 1405, this gothic-esque tomb stands at odds with the surrounding Romanesque design, but ensures that the prior himself will never be ignored by parishioners and tourists alike. Rahere is shown lying atop his tomb, hands pressed together, while the figures either side hold open bibles that read (Isiah 51) God “will comfort all her waste places; and he will make her wilderness like Eden, and her Desert like the garden of the Lord.”

There are too many grand memorials to fit into just one post, and so many paintings and aspects to the church that would take thousands more words to cover, but I’m sure we’ll return to them soon enough. Until then…

St Bartholomew’s the Great is celebrating its 900th anniversary, so if you find yourself in the city and need a bit of solace, pop in and take a moment to enjoy the quiet history around you.

***

Liked this post? Then why not join the Patreon clubhouse? From as little as £1 a month, you’ll get access to tonnes of exclusive content and a huge archive of articles, videos and podcasts!

Pop on over, support my work, have a chat and let me show you my skulls…

www.patreon.com/burialsandbeyond

Liked this and want to buy me a coffee? To tip me £3 and help me out with hosting, click the link below!

https://ko-fi.com/burialsandbeyond

***

Further Reading:

https://www.greatstbarts.com/filming/

https://baldwinhamey.wordpress.com/2012/11/14/edward-cooke/

[1]https://baldwinhamey.wordpress.com/2012/11/14/edward-cooke/

Leave a comment