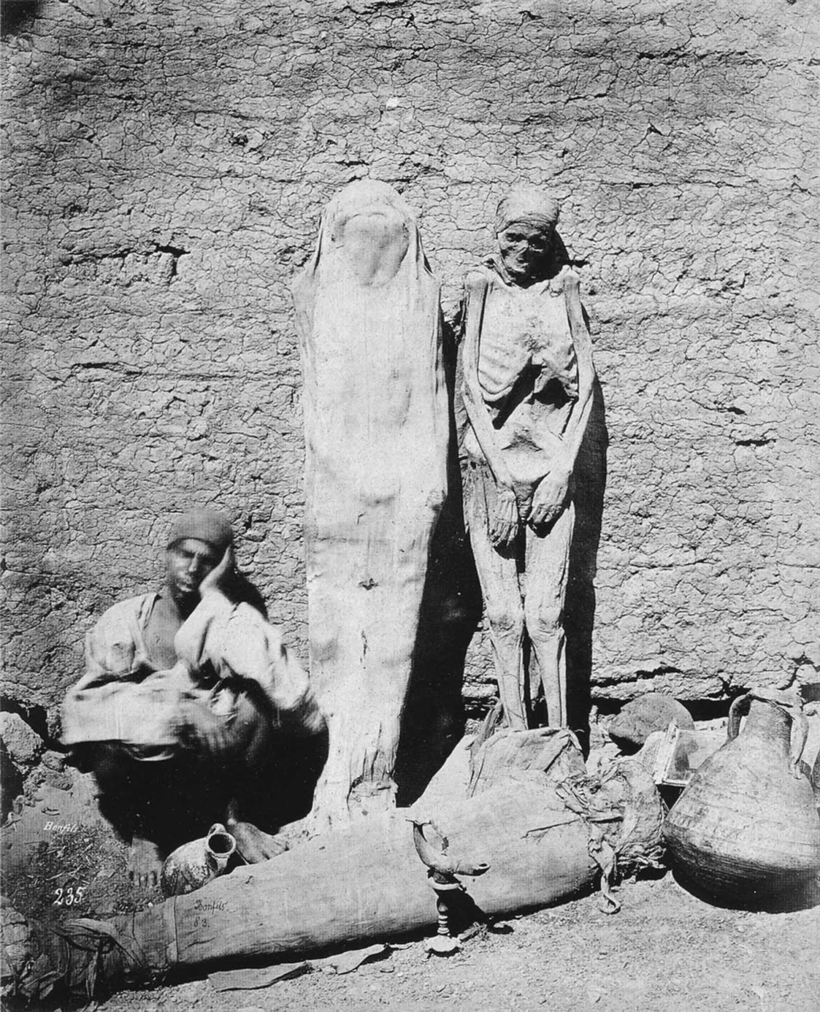

CW: Mummified human remains

In the 19th century, ‘Mummy Mania’ spread through the western world like a colonial Tamagotchi. Those in Victorian high society were soon trading their evenings watching a play for evenings at a slightly different type of theatre.

Mummy parties or ‘unwrapping parties’ were de rigueur in London society, where imported Egyptian mummies would be unwrapped at private parties for the enjoyment of the assembled sitters. This particular wave of Mummy-Mania (for there had been many before, previously focusing on the restorative powers of consuming mummies) began in 1798, following Napoleon’s first expedition to Egypt where he sought to develop French trade links in Egypt and Syria. This campaign allowed Europe’s wealthiest to develop this new interest and travel to Egypt themselves, bringing a few oversized souvenirs back with them.

Mummies were plentiful on the streets of Egypt, obtained and sold by graverobbers in search of quick foreign money. Both sides of the transaction did not afford the deceased any level of dignity or respect, passing off a human cadaver as a fun and exotic novelty; the ideal party piece for the wealthy communities who have everything. That’s not to say that the graverobbers were wholly to blame – while they desecrated their country’s history, extreme poverty would push individuals to such extremes, feeding into a trade developed and supported by damaging Western attitudes and the ‘othering’ of communities in the far east.

The bodies of mummified Egyptians had long been regarded as a mystical medical resource. For many years, mummies were disinterred, sold to the west, ground into a powder and consumed as a remedy for a variety of ailments, often as a moulded tablet simply called ‘Mummy’. The demand for real powdered mummy was so great that the market was soon flooded with counterfeit flesh, being the powdered remains of Egyptians dying in extreme poverty. This same powder was also marketed as an artists’ pigment named ‘mummy brown’ or ‘Egyptian brown’. When the true source of this popular pigment was recognised, ethical issues arose in their infancy. Meanwhile artist Edward Burne-Jones ceremonially buried his tube of mummy paint in his back garden, disgusted with its human origins.

Mummies were a resource to be used by growing worlds of industry, both in the western world and at home in Egypt. Mark Twain once reported in ‘The Innocents Abroad’ (1869) that he witnessed mummies burned as fuel for Egypt’s growing railway system, saying ‘three thousand years old, purchased by the ton or by the graveyard for that purpose, and … sometimes one hears the profane engineer call out pettishly, ‘D–n these plebeians, they don’t burn worth a cent — pass out a King!’[1] yet, for all the many uses of mummies, this is simply an oft-repeated joke. However, in the United States, there is rather more evidence to support the claim that mummy rags – the bandages binding the bodies – were imported en masse for the paper trade during the American Civil War. Combining linen bandages and imported mummy rags, paper makers could produce a rough brown paper that would be ‘sold to shopkeepers, grocers, and butchers, who used [them] for wrapping paper.’[2] Other reports suggest that mummies were used to create fertilizer in the UK and in Germany.

However for Victorians at the tail end of the 19th century, whole mummies became popular objet d’art for the great and good of the western world. Alongside mummy parties, parts – namely feet and hands – of long-dead Egyptians were desired as macabre souvenirs, and as an affordable alternative to an entire cadaver.

Before mummies found their way onto upmarket dining tables, the earliest unwrapping parties were presented as pseudo-medical affairs. Considering that public operations and autopsies had been popular events for decades, the unwrapping of a desiccated cadaver seems rather tame in comparison.

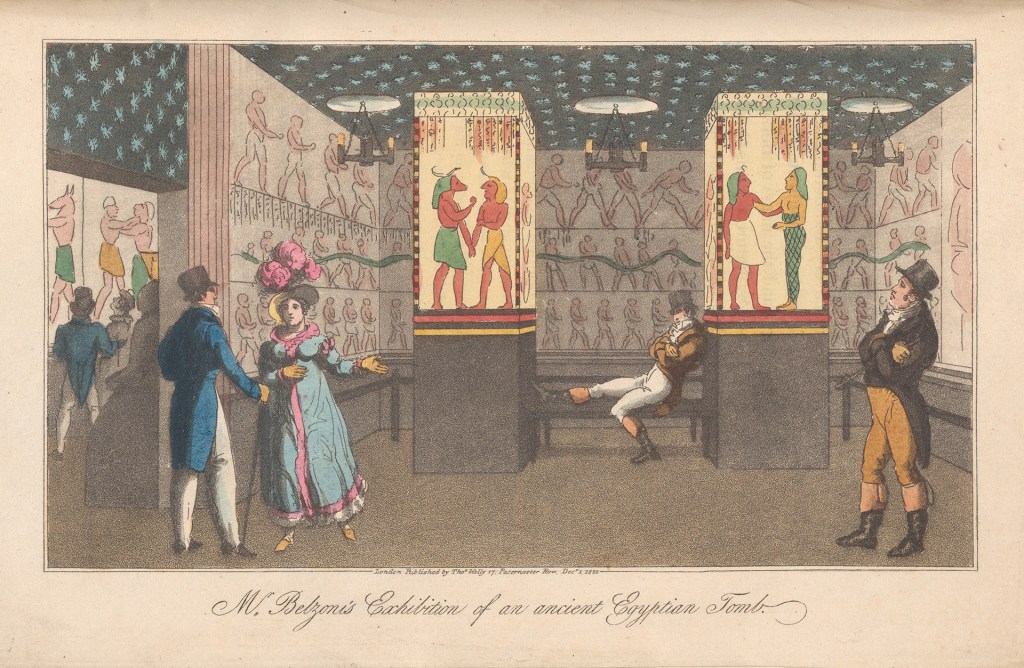

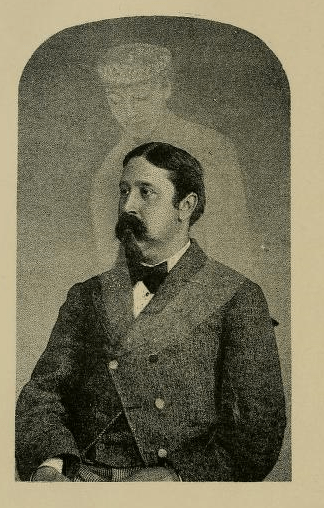

It’s generally believed that the first ‘unwrapping’ public event was conducted by archaeologist Giovanni Belzoni (1778-1823), who – in 1821, unwrapped a cadaver in Piccadilly Circus to a reported audience of thousands! Known as ‘The Great Belzoni’, Giovanni was a prominent Italian explorer with a taste for showmanship (aided by his former career as a circus strongman), and kicked-off the era of mummy desecration with his own discoveries in Egypt, most notably his unearthing of the mummy at Psammethis. After travelling to Egypt with the intention of selling hydrological equipment, he ended up working for the British Consul General and was soon immersed in the transport of ancient artefacts. Belzoni was involved in several important excavations, including at the temples of Edfu, Philae and Elephantine[1] and would enter the pyramid of Khafre at Giza in 1818. This latter act would be a career triumph, making him the first modern explorer to enter the inner chambers of the pyramid. After returning home in 1819, he published his findings in ‘Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries within the Pyramids, Temples, Tombs and Excavations in Egypt and Nubia’, regarded as the first English-language work in Egyptology.

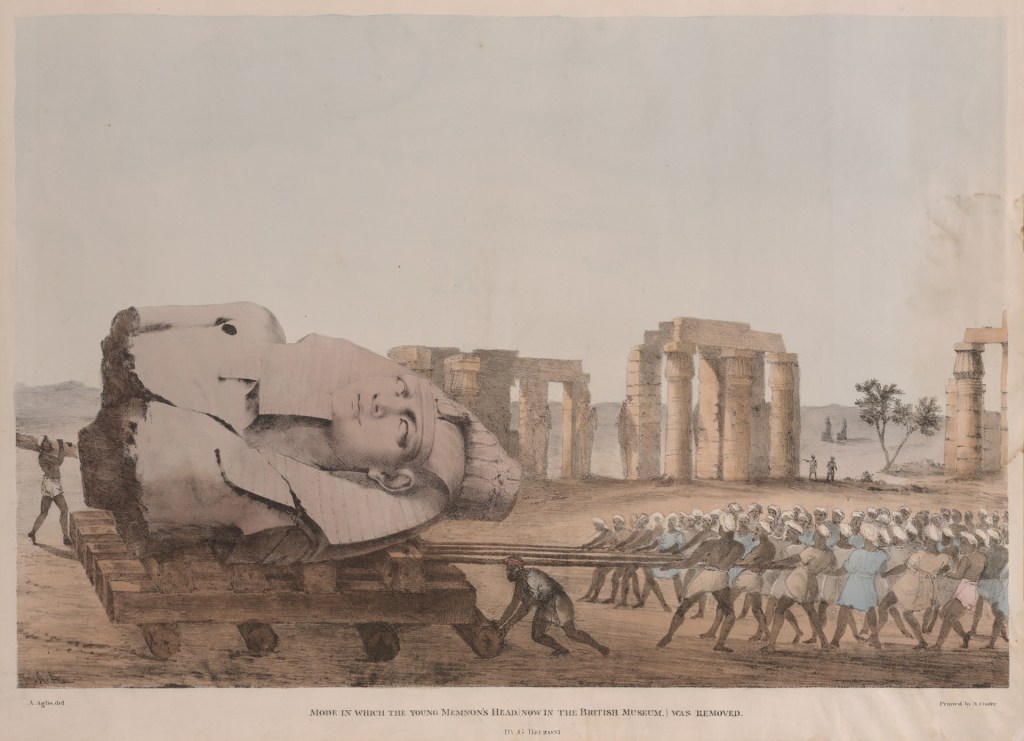

Between 1820-21, he would place many of his personal ‘findings’ on public view, staging a substantial year-long exhibition in Picadilly’s Egyptian Hall and later, taking his models to Paris. These ‘findings’ were ultimately looted objects, and included a white alabaster sarcophagus from Seti I’s tomb and the head of the ‘Younger Memnon’. Following this exhibition, the contents were put up for sale, with two of the greatest bidders being Sir John Soane and The British Museum (who acquired the sarcophagus and head respectively).

Prior to their sale, Belzoni was said to have popularised the exhibition at the Egyptian Hall with a ‘mummy unwrapping party’, wrapping himself in bandages to welcome the guests, before the ancient cadaver was brought out. Assisting Belzoni in this first unwrapping was surgeon Thomas Pettigrew, who grabbed and ran with the party theme for years to come (although some of these later mummies may have been snatched from English burial grounds under cover of darkness, rather than Egyptian tombs). Advertised as an event for medical professionals, Belzoni’s biographer regarded it as ‘a shrewdly-aimed advertisement, calculated to bring in a large body of professional men.’[2] Following its unravelling, Belzoni’s mummy was ‘displayed, alongside a motley collection of Egyptian artefacts, at the Egyptian Hall.’[3]

While not the first to conduct a mummy-unwrapping party, Surgeon Thomas Pettigrew would popularise the format by performing a mummy unwrapping at the Royal College of Surgeons in 1834, with his series of unwrappings gaining him the nickname ‘Mummy Pettigrew’. According to the Old Operating Theatre Museum, ‘The mummy unwrappings (or unrollings) themselves usually had the same format. The body was presented on a table surrounded by the symbols of Egypt including funerary hieroglyphics, and a lecture [was delivered].’ The unrolling itself – for Pettigrew’s initial events at least – involved ‘separating the different layers of bandaging, removing amulets from their layers as progress was made, eventually revealing the body itself. An examination would be made of it, remarking on its situation as the unrolling progressed and observing things about it, such as body decorations, presence of hair, pliability of skin and guessing at ethnicity.’[3]

However, while Pettigrew may have popularised unwrappings, a ‘have a go’ attitude developed very quickly. The fanciest dinner parties would host their own events – presumably after dinner, to save a little sickness – where bandages could be unwrapped and bones could be exposed, all in the comfort of your own living room. These affairs were far from the sedate origins of the operating theatre and were often very rowdy and boozy affairs. Imagine the British Museum mixed with Saturday night down your local Wetherspoons.

Thankfully, mummy unwrapping parties ended as the 20th century began. Egyptomania became collectomania with the advent of Howard Carter’s expedition and the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb. A little more respect for Egypt’s remaining history emerged following these archaeological expeditions, despite the ever-present black market in antiquities. We can never know how many mummies were lost to paint, fuel, tablets or parties, but I’m certainly glad that my dinner table has been cadaver-free since purchase. Well, for now at least.

References/Resources:

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/egyptian-mummy-seller-1865/

https://oldoperatingtheatre.com/dr-thomas-joseph-pettigrew-a-k-a-mummy-pettigrew-a-short-biography/

https://artuk.org/discover/stories/the-corpse-on-the-canvas-the-story-of-mummy-brown-paint

https://cemeteryclub.wordpress.com/2019/10/31/ooh-lumme-its-pettigrew-a-mummy/

https://shadow-plays.supdigital.org/sp/chapter-4-section-3

Kirsty Chilton, “Dr. Thomas Joseph Pettigrew, a.k.a.Mummy Pettygrew: A Short Biography”, Museum Highlights (blog on oldoperatingtheatre.com), October 18, 2016.

MOSHENSKA, GABRIEL. “Unrolling Egyptian Mummies in Nineteenth-Century Britain.” The British Journal for the History of Science, vol. 47, no. 3, 2014, pp. 451–77. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43820513.

[1]https://www.straightdope.com/21343478/do-egyptians-burn-mummies-as-fuel

[2]https://www.ajaonline.org/book-review/1184

[3]https://oldoperatingtheatre.com/dr-thomas-joseph-pettigrew-a-k-a-mummy-pettigrew-a-short-biography/

[1] https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Giovanni_Battista_Belzoni

[2] Stanley Mayes, the Great Belzoni, London: Putnam, 1959, p.260

[3] Gabriel Moshenska, Unrolling Egyptian mummies in nineteenth-century Britain, British Journal for the History of Science, vol 47. No. 3 (Sept 2014) pp 451-177.

Leave a comment