The finest treasures are often found in the most unexpected places. In the village of Kingerby in Lincolnshire sits a tiny, old redundant church. It’s surrounded by trees, angry bugs and large metal gates. If you didn’t know it was there, it’d be easy to drive past, if you even found yourself on the tiny backroad in the first place.

The church building is a real hidden gem; tiny, grade I listed, made of limestone rubble and with masonry from the 11th-17th centuries. Heck, the church even has associations with ancient lords and the king of animation himself, Walt Disney. And as the icing on the cake? Two enormous knights lie within.

The name Kingerby derives from the Danish words ‘Cynehere’s by’ or Cynehere’s Village, but archaeological findings point to a far earlier, Bronze age settlement occupying the site. Kingerby village was listed in the Domesday book as being owned by the Bishop of Bayeaux and Goscelin, but all former seats of power have since succumbed to the hands of time. Kingerby manor – originally a motte and bailey castle – burned down in 1216 and was then rebuilt during the 14th and 15th centuries where it was the family home of the Disney family. The manor, or the estate of Kingerby Hall was owned by Roman Catholic families between the 17th and 19th centuries, where they used their family seat to conceal priests from persecution during the reformation period. The last family to own the manor were the Young family, but the manor (the current residence was built in 1812) still stands and is a grade II listed building.

Kingerby is often described as ‘simple’ and ‘unspoilt’, and for the most part, this is correct. St Peters is a compact church – the 12th century (or earlier) tower is the earliest part of the building, while the rest seems to date from the 13th/14th centuries, with a later 17th century roof. The doorway to the porch is 13th century in origin – and looks as such, being weathered and wonky with distinctive dog toothed pattern to the sides. However, the church doorway is both smaller and older, being 12th century, but is simple and rounded, giving few indicators of what treasures lie within.

The church once served a larger village which has long since disappeared, leaving only the church, leafy roads and barely enough houses to constitute a hamlet. However, in the days of community living, the aforementioned family of landed gentry, the Disneys, oversaw Kingerby throughout the 14th and 15th centuries. The Disney family were closely associated with royalty, with Sir William Disney fighting alongside Edward, The Black Prince (1330-1376) and the nearby village of Norton Disney holding the family’s name for centuries to come.

These Lincolnshire Disneys were direct ancestors of THE Walt Disney. In 1949, Walt himself visited Lincolnshire to trace his family history and spent time visiting prominent Disney sites. When visiting his namesake village, he passed by several family memorials, brasses and the local pub, leaving a handful of ‘prints’ as a gift to the village hall, which remain there today – sun-faded, but present. While he visited Norton Disney, he doesn’t seem to have visited all of his grand ancestral graves and Kingerby was completely missed by Walt and family.

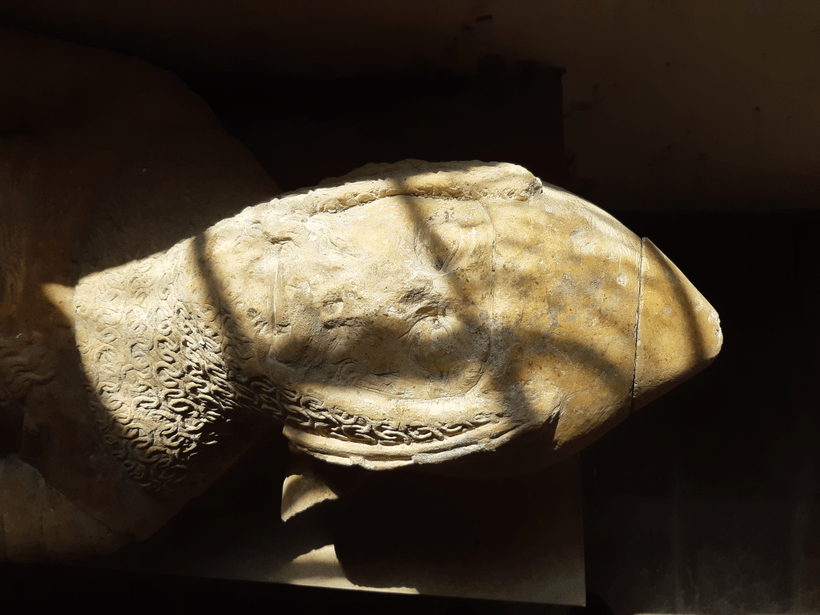

Inside the church of St Peter sit two huge knightly monuments, commemorating the lives of Disney knights in the forms of large 14th century effigies. Unlike many effigy tombs that have succumbed to weathering or the over-keen hammers of civil war or reformation revolutionaries, these 14th century knights have survived remarkably intact. The detail on the chain mail and clothing, carved in spectacular relief appears as clean and crisp in the sunlight as the day it was carved. Well, give or take a century.

The first knight, dressed in chain mail – an effigy on top of a chest tomb – is believed to be Sir William Disney Sr, a friend to Edward II – the three Plantagenet lions on his clothing give a few indicators as to his affiliations. His legs are crossed, and he rests with puppies beside his pillow – the perfect way to spend eternity.

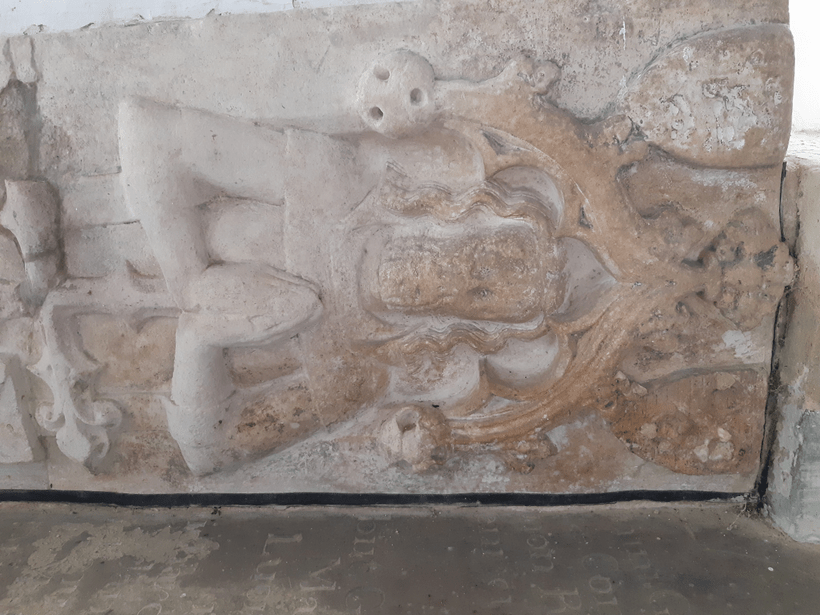

The effigy beside this is most likely that of William Sr’s son, William, wearing plate armour, rather than chain mail. While his father’s lion designs are easily identifiable, William Jr’s choice of heraldic beasts are rather more…fantastical in appearance (although are probably just lions too). Sadly, William Jr was not to die valiantly in battle, but during the ‘Black Death’ plague of 1349. His effigy has been somewhat truncated (shortened) at some point, where a large portion of his legs were removed and lost. But why they were removed, or lost, in the first place is unclear. The figure’s hands are in prayer, and his feet are resting on a dog. You can’t keep Disneys away from cute animals, even in death.

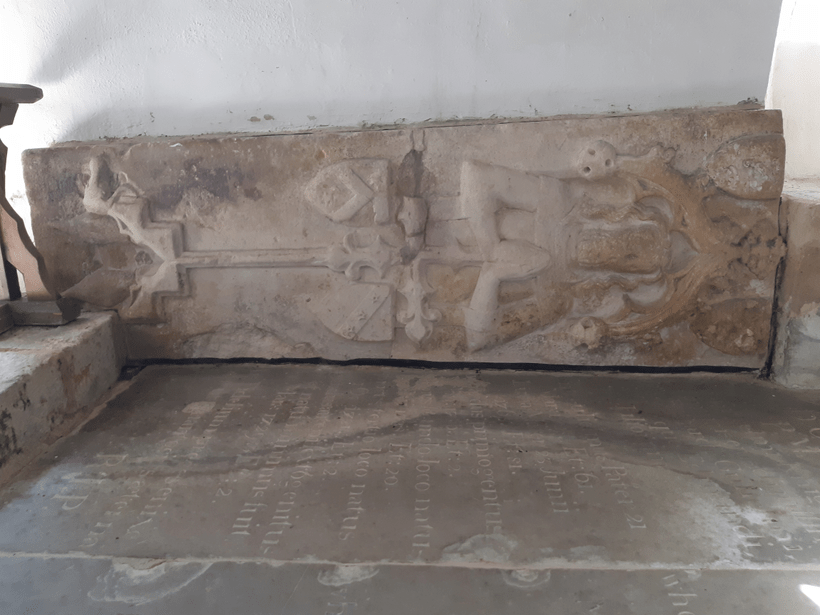

Towards the back of the church is a somewhat simpler, but just as spectacular piece of late 14th century memorial masonry. Another knight – probably being another member of the Disney family – is carved in relief from a huge slab of stone, depicted in prayer, with flowing Marti Pellow-esque hair and a cross sitting in place of his legs.

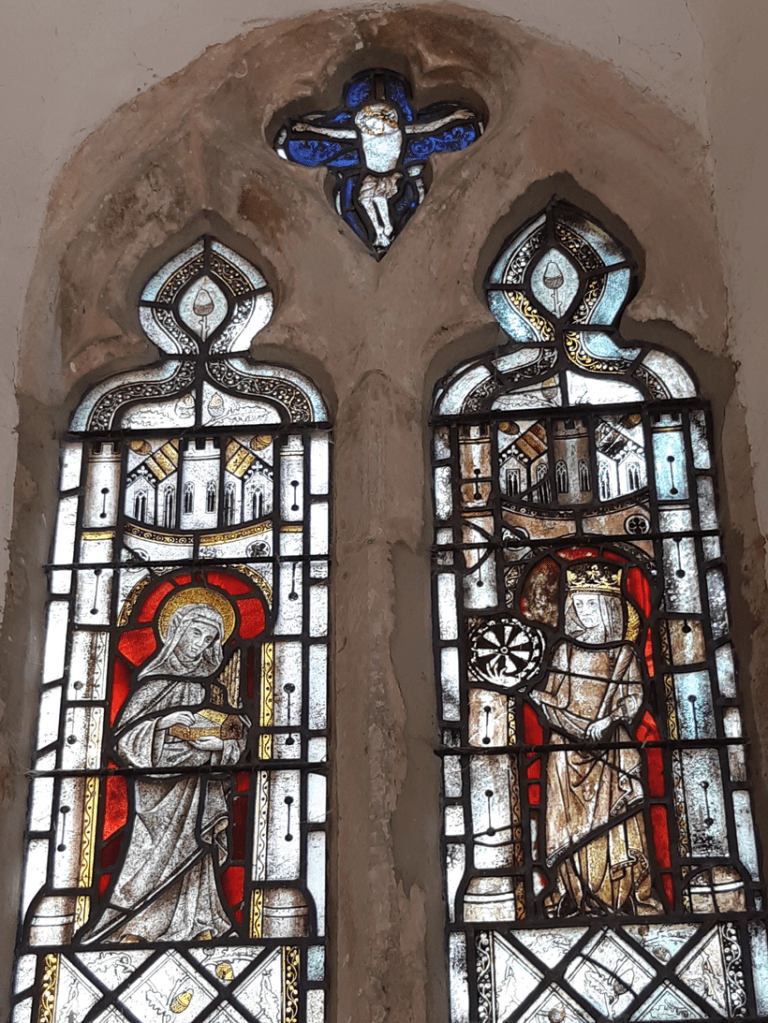

The stained glass windows are just as unusual as the building’s knightly inhabitants, including one depicting female catholic martyrs. One two-light window depicts Saint Cecilia, patron saint of music, playing a small organ and is a 19th century copy of the original (presumably 15th century). Beside her is Saint Catherine (original 15th century) holding the wheel on which she was martyred. Or, standing at the oche for a game of darts, depending on your angle.

There are many other small treasures within the church – a 13th century octagonal font, tiny choir stalls that use late medieval bench ends and 17th century woodwork in the roof. The oak lectern isn’t original to Kingerby but originated in south Kelsey church, purchased in 1939 for £1. The pulpit similarly originated in another church, given to Kingerby by Holy Rood Mission church in Lincoln in 1948.

The pulpit had been purpose built for Holy Rood and was far too large for Kingerby’s doors – a fact only discovered when the pulpit reached the churchyard. According to ‘Notes on the history of St Peter’s Kingerby’ by the former vicar of Kingerby Rev George Percival Morris, it took ‘a master carpenter and his son two and three quarter hours to cut the pulpit in halves’ before being re-joined inside the building.

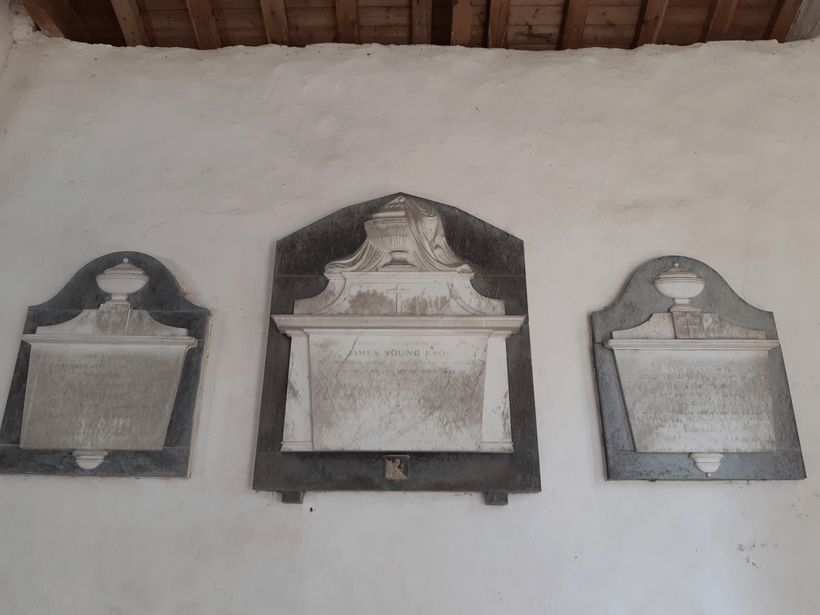

A handful of wall memorials to the Young family of Kingerby Hall are somewhat dwarfed by the enormous knights, but show the importance of the church building well into the 19th century.

The churchyard has a handful of interesting memorials, including an unusual barrel tomb with a large dove motif and no discernible epitaph. Many have been removed over time, but are broadly 18th and 19th century (with a handful of outliers) and virtually illegible from moss growth.

As with many rural churches, it has been redundant for some time and was taken into the care of the Churches Conservation trust in 1982. While this was the death-knell for Kingerby in its old form, this ensured the survival of the church and its preservation – and accessibility – for centuries more to come.

***

Liked this post? Then why not join the Patreon clubhouse? From as little as £1 a month, you’ll get access to tonnes of exclusive content and a huge archive of articles, videos and podcasts!

Pop on over, support my work, have a chat and let me show you my skulls…

www.patreon.com/burialsandbeyond

Liked this and want to buy me a coffee?

To tip me £3 and help me out with hosting, click the link below!

https://ko-fi.com/burialsandbeyond

***

https://www.visitchurches.org.uk/visit/church-listing/st-peter-kingerby.html

https://www.britainexpress.com/counties/lincs/churches/Kingerby.htm

Leave a comment