Cemeteries can be awkwardly placed things, on city outskirts or in less-that salubrious places where you’re more likely to stumble across a crack den than an intact mausoleum. York cemetery, however, was designed with the modern minivan in mind, and made for a rather lovely – if rainy – day out.

Opened in 1837, York Cemetery was one of the UK’s earliest Victorian garden cemeteries, designed with the single aim of relieving the strain on local churchyards, which – like many others – were bursting at the seams. During the 19th century, many churchyards had become incredibly overcrowded and were public health risks as a result. Not only were the grounds whiffy and dangerous, but many graveyards were now several feet above ground level and physically could not hold any more bodies. As such, places like York Cemetery became a necessity.

Initially, York’s new sprawling burial ground was treated with a little suspicion, and wasn’t the first choice for the deceased great and good of the city. However, York council issued a closure order for all existing burial grounds in 1854, and the cemetery finally had the monopoly on York’s mortal coil.

The York Cemetery Company was established as a joint enterprise business, not so much for the greater public need, but for profit. After the council’s order to close graveyards, the cemetery grew at a great rate, reaching 24 acres, and right through to the 1940s, the cemetery paid healthy dividends to its many shareholders.

However, boom time was not to last and in 1966, the cemetery went into voluntary liquidation. This ‘voluntary liquidation’ lasted thirteen long years, where everything worth anything was sold off to the highest bidder. There were no shareholders or caretakers to tend to the site and no thought was given to burial rites, access, or maintenance. When the site devolved into the possession of the Crown, it was in a terrible state of disrepair.

Overgrown, unloved and dangerous, the cemetery’s survival hung in the balance for decades. That was until 1984, when the – pardon the pun – final nail in the coffin forced concerned residents into action. The roof of the Grade II listed chapel collapsed, leaving the site a macabre, derelict site. Inspired to action, The Friends of York Cemetery – now the York Cemetery Trust – was formed, saving the site and spending decades fundraising and restoring the sprawling site, stone by stone. Like many other large Victorian cemeteries, part of the grounds are set aside for flora and wildlife, with everything else enjoying a basic once-over with the lawnmower. It’s a far cry from the once well-sculpted garden landscape, but cuts a beautiful and rather gothic silhouette in its own way.

The chapel, gatehouse, wrought iron fence and six memorial stones are Grade II listed and regarded as being of significant importance.

The cemetery chapel was restored and re-roofed in the late 80s, thanks to the donations and fundraising efforts of the newly-formed trust. Designed by architect James Piggot Pritchett, it was one of the original focal points of the initial cemetery design and is of quite considerable size. The chapel design is starkly neo-classical and was based on the temple of Erectheus in Athens, considered to be one of his greatest remaining commissions. Its little wonder that the space has been commandeered for events and gothic club nights these days!

The catacombs of York were one of the most striking – and useless – buildings on site. As delightfully gothic as catacombs look, they were an expensive addition to many cemeteries that never really took off as intended. Due to the cost and suspicions around this new method of body disposal, the catacombs closed long before the turn of the century. Since opening, only 17 people were interred within the catacombs, with the last sliding into place in August 1881.

The Graves

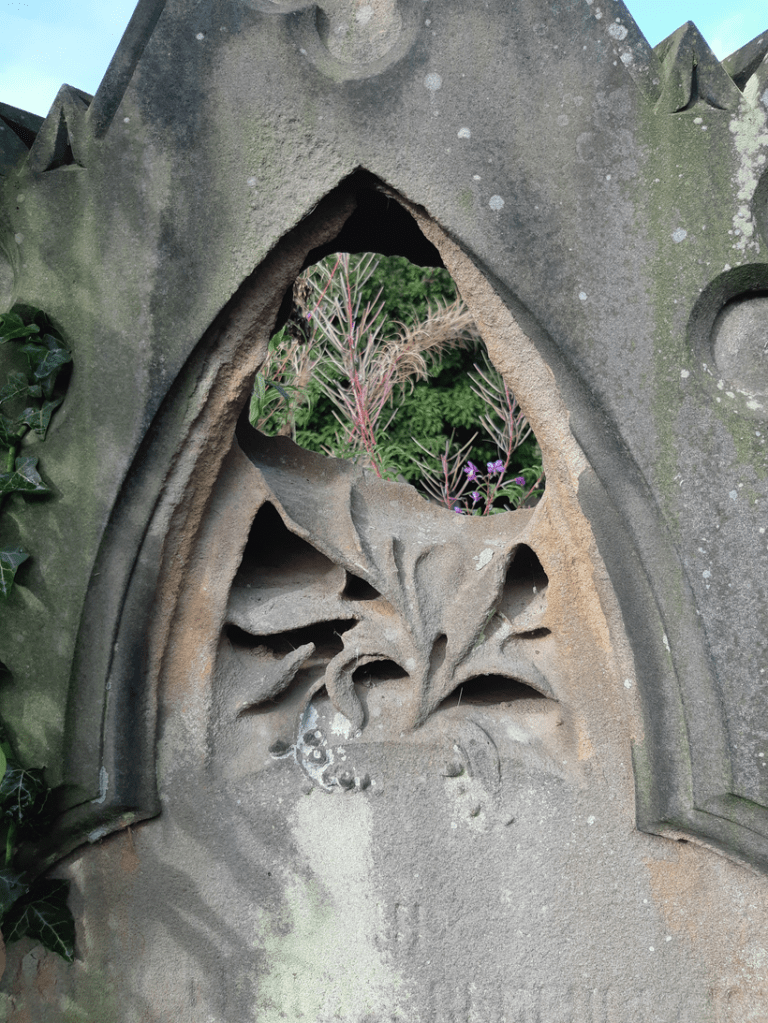

There are countless grave styles and eras across the cemetery, some of which I’ve never seen before, especially in terms of unique decoration.

As always, the children’s section is particularly poignant with tiny headstones and biblical epitaphs, commemorating lives cut painfully short.

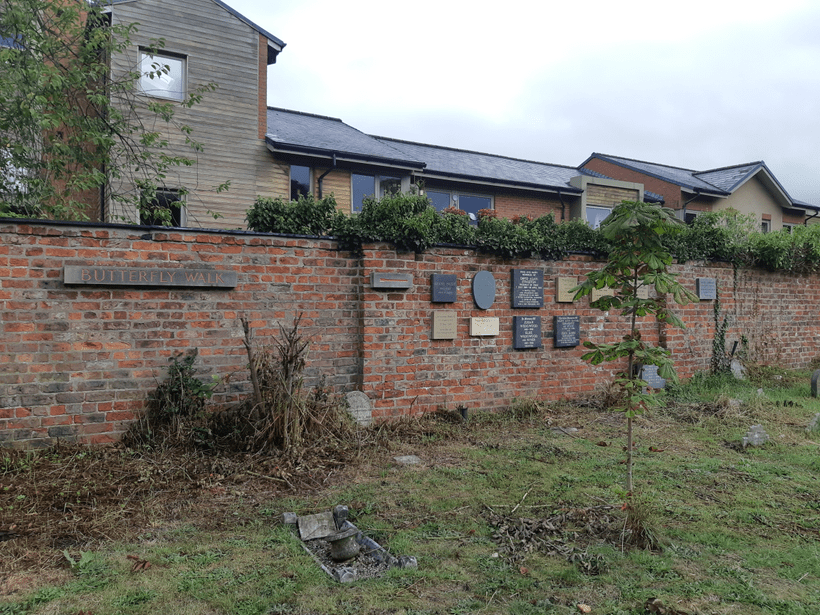

Beside this area, a plaque bearing the optimistic name ‘Butterfly Walk’ (I was very much out of season for butterflies, and the half-dead plants did little to help things) is affixed to a wall, beside more memorials for adults, rather than children.

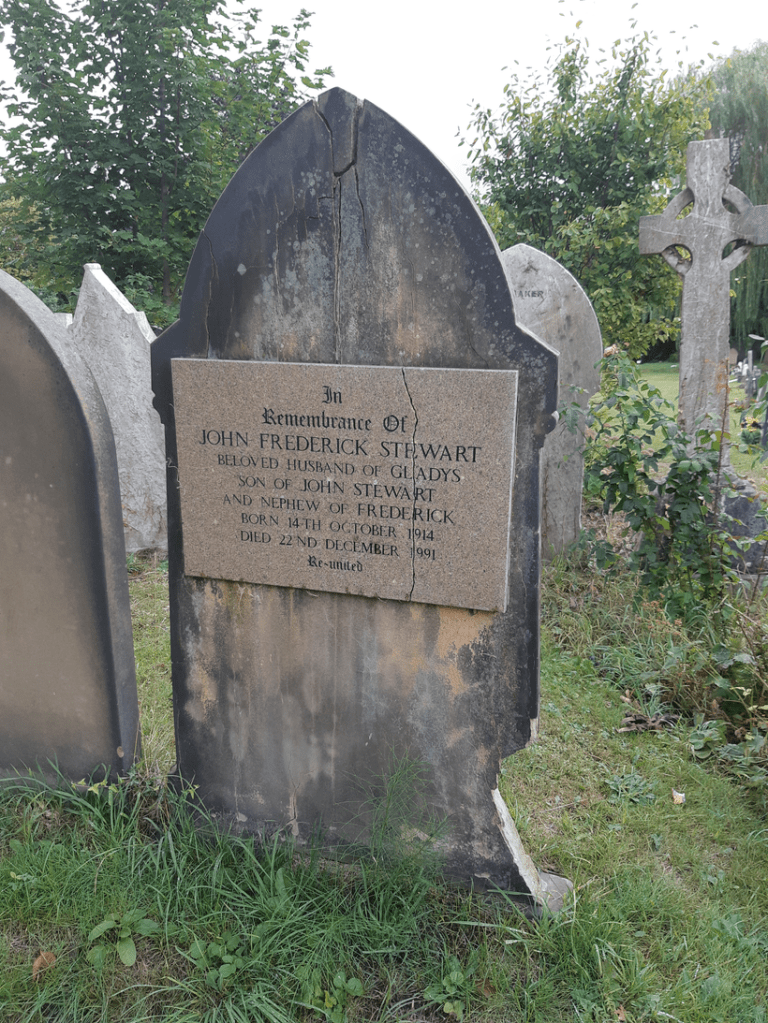

Many of the early 20th century headstones are homogenised in design, with simple carvings of ivy, grapes and clasped hands, with a few decorative ornaments between interments. A handful of headstones unusually have additional memorial plaques affixed to the back in far newer, contrasting materials. While this might be commonplace in York, I’d never seen this cross-generational masonry collaging before.

Naturally, there are a number of notable local figures within York Cemetery, and for those with the time and inclination, several routes have been laid out by the Friends group, should you want to see all the sights. However, for my trip – hastily tagged on to the end of a conference – I was grabbing dead politicians where I could.

One such notable local was James Birch, JP. Alderman and twice Lord Mayor of York. He died in 1913 and is commemorated with a rather substantial Celtic cross monument.

After snooping for a little more information about James, I fell across the photograph archive of a tram enthusiast. Within these images was a photograph from 20th January 1910, where Alderman James Birch was taking a ride on one of York’s new, futuristic electric trams. While these were a very exciting addition to the city’s streets, they enjoyed only a brief moment in the sun, ceasing functionality by 1935. According to one of the cemetery’s many trails, a summary of Birch’s life is as follows:

“James Birch was born in York and was educated at Priory Street School (now a Community Centre).

He ran a Plumbing and Glazing business in Blossom Street, and was a keen sportsman. He was a forward with the original York Rugby Club and sometime Chairman of York Cricket Club.

His position in the role of Lord Mayors is unique. He was the first to be elected to the office from amongst the ordinary Councillors since the 1835 Municipal Corporations Reform Act. He was granted Freedom of the City in 1878 and died on 07 July 1913, aged 57, leaving Effects of £5,663.”

A wander deeper into the cemetery brought me to the grave of Sergeant J. W. Raftery MM, who was killed in action on April 25th 1918, aged just 24. While I’m no military historian, in recent years, I’ve tried to make an effort to document any war grave I find – I suppose I’m thinking that it might help someone’s family research some day? I’m not sure. It’s a compulsion I’m yet to understand.

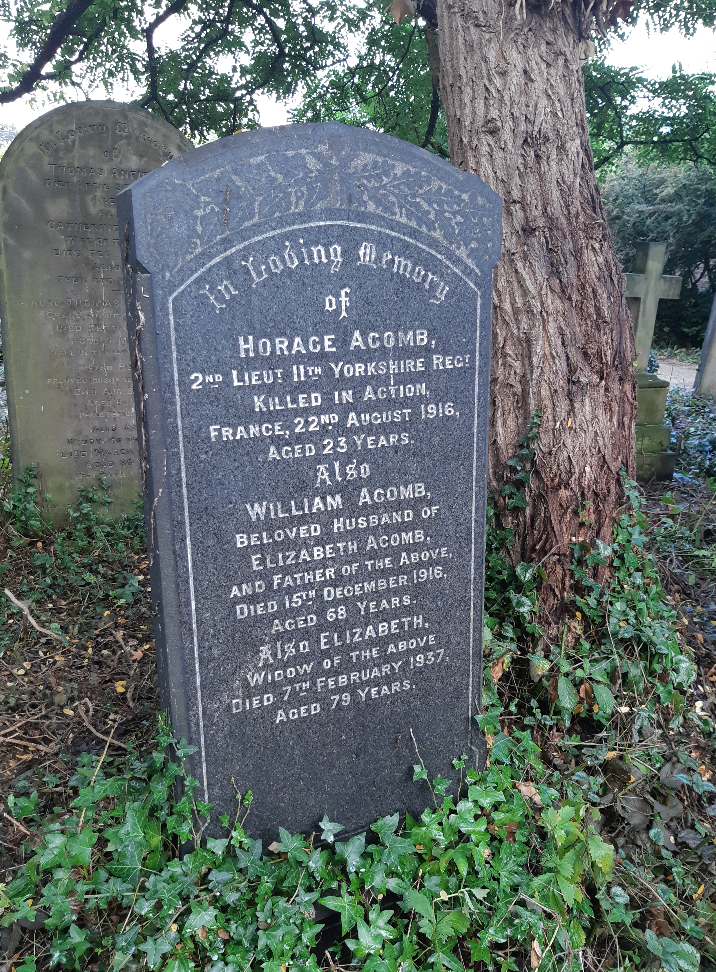

Similarly, the grave of Horace Acomb, 2nd lieutenant with the 11th Yorkshire regiment was close by. Killed in action in France on 22nd August 1916, he was just 23.

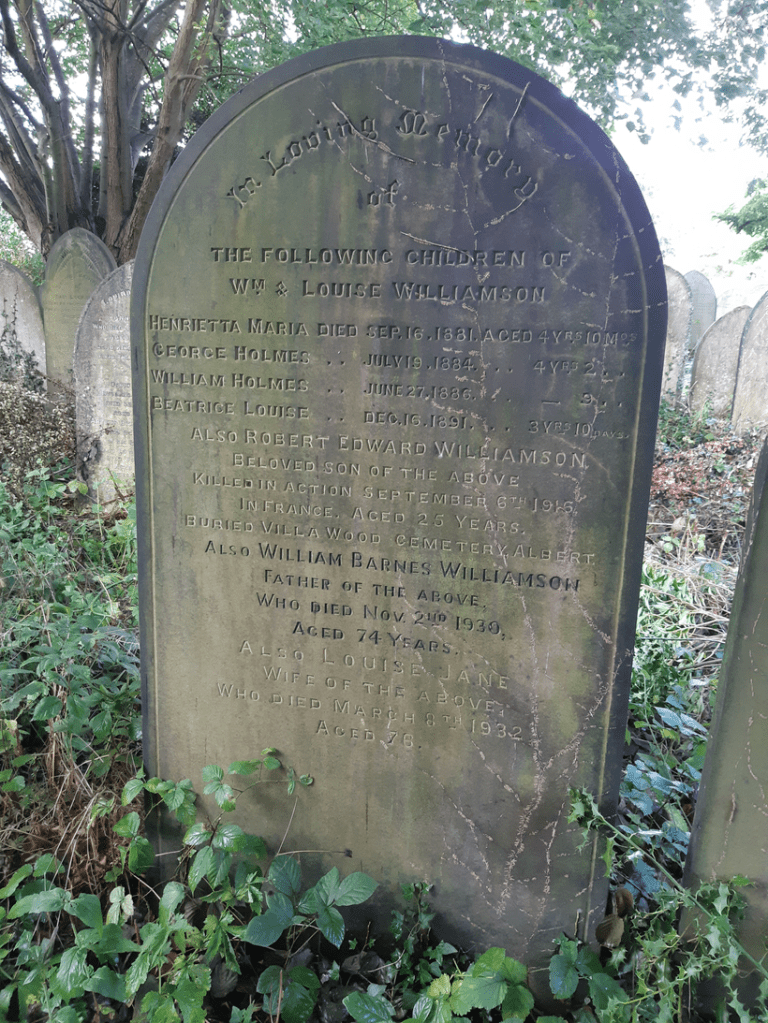

One particular grave that caught in my throat was more of a list than a standard memorial. A large headstone with small text reads ‘In loving memory of the following children of William and Louise Williamson.

Henrietta Maria died Sep 16 1881 aged 4 yrs 10 months

George Holmes died July 19 1884 aged 4 yrs 2 months

William Holmes died June 27 1886 aged 9 months

Beatrice Louise died Dec 16 1891 aged 3 yrs 10 days

Also Robert Edward Williamson, beloved son of the above.

Killed in action September 6th 1916 in France, aged 25 years.

Buried Villa Wood Cemetery, Albert.‘

William and Louise died in 1930 and 1932 respectively.

How any family could continue after such immense loss amazes me, and the pain at losing so many children must have been unbearable. My own great-grandparents lost similar numbers of children to disease and war, and I cannot comprehend how they carried on with their lives – one presumes for the wellbeing of those who are left behind.

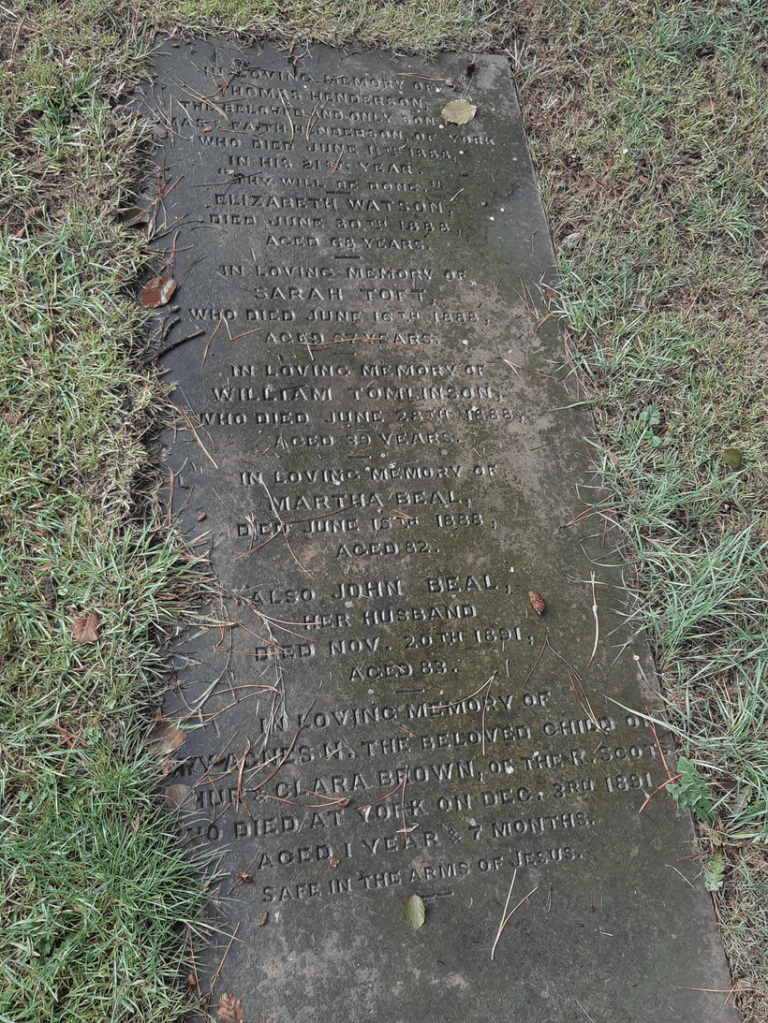

Many other headstones list large numbers of family members, all having died in quick succession. Others list large numbers of people with no personal connections at all – presumably all too poor or isolated to afford their own plot. Most of these were in the form of ledgers; large rectangular slabs set into the ground close to the central walkway.

Another headstone that caught my eye was that of Elizabeth Battye, wife of Wright Battye. Elizabeth died in 1872 aged 49. In life, the Battyes had operated The Golden Slipper in York, a pub which still survives today!

Other interesting graves were that of successful hotelier William Thomas of Museum Street, whose obelisk had all manner of symbols affixed to each side.

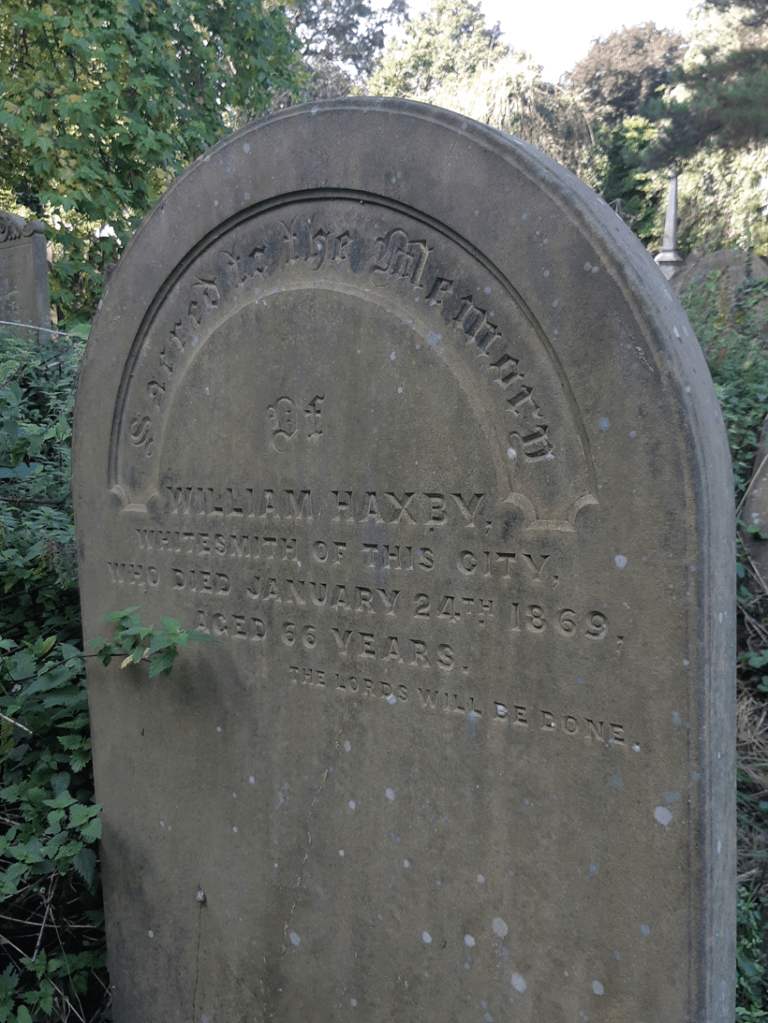

William Haxby’s (d.1869) grave lists an unusual occupation title, a ‘whitesmith’. According to our old favourite, Wikipedia, a whitesmith ‘is a metalworker who does finishing work on iron and steel such as filing, lathing, burnishing or polishing. The term also refers to a person who works with “white” or light-coloured metals, and is sometimes used as a synonym for tinsmith.’

Peter Mortimer’s grave not only lists his date of death, but the manner in which he died, aged 28.

‘The result of an accident at York Railway Station.

Dead did to me, short warning give.

Therefore be careful how you live.

My dearest friends I’ve left behind

And had not time to speak my mind

In the midst of life we are in death.’

Peter and his wife Sarah had two children by the age of 21, with Peter supporting the family with his wages as a grocer and provisions dealer. However, aged 28, he was working as a labourer and assistant shunter at the carriage works. According to reports,

‘At about 17.00 hrs on 9 September 1882 he was working in the sidings near the old railway station in Toft Green (the site of the City of York Council offices) when he found himself positioned between a stationary and a moving train. He was caught by the steps of two of the carriages and was severely crushed. He died 2 hours later in hospital.’

He left behind a 5 year old and a 3 year old. Sarah would later remarry, but is buried with Peter, her first love.

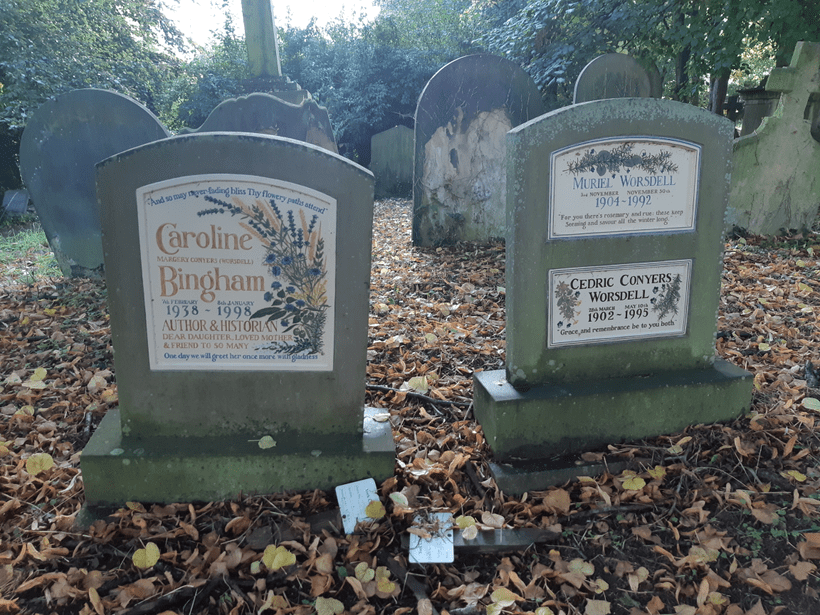

Some of York’s most unusual graves weren’t large monuments, but intricately decorated porcelain plates. Two graves glistened against the backdrop of orange leaves and muddy stone, painted with wildflowers and greenery in a beautiful and unique memorial – and one that fits well with the environment too!

Caroline Bingham was an author and historian with a particular interest in Scottish history and the Scottish monarchy. Her first work, The Making of a King: The Early Years of James VI and I (1968) set the scene for her later, enormous double volume work which looked into the later reign of James in England and Scotland. She never took up an academic post, preferring to have full independence and write for the common reader rather than a specialist audience. Her lengthy obituary can be found here and makes for interesting reading – https://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/obituary-caroline-bingham-1138921.html

Beside Caroline’s grave is that of her parents, Muriel and Cedric Worsdell, fitted with two separate plaques featuring different flowers and quotes in an incredibly sweet memorial.

Turning a corner will bring you face to face with a frankly enormous cross, marking the grave of the Dickinson family, most prominently Alfred Dickinson, a spirit merchant.

Another large, but significantly more weathered memorial, is that belonging to the Rev. Adolphus Hamilton, the late minister of Holgate district, who died age 38 and whose stone was funded by members of his congregation.

Another unusual, but decidedly more modest headstone, features two angels back to back and marks the resting place of Richmond Henty, one of Australia’s ‘pioneers’. An unusual term, it refers to the Brits who emigrated to Australia of their own free will, rather than on convict ships.

[Can’t do much about a misplaced apostrophe when its laminated…]

Oh, and beside all of this, York Cemetery has bees. So many bees.

What appears to be a bird bath, encircled by arms, sits just off one of the many cemetery paths. A multi-functional memorial, it can be enjoyed by visitors, both human and feathered.

Finally, I stumbled across the most curious, unsettling and wonderful memorial – one more befitting to a church than a cemetery – and one that left me absolutely clueless as to its origin and who on earth it belonged too. Sitting a little down from a bank, this shrouded human likeness sits at a strange angle, covered in moss and easily overlooked by any passer by. More child-sized than adult, but depicting a man with cherub heads to his side, it seems to be a Victorian replica (the date 1874 can be read) of a far older effigy memorial or cadaver tomb.

Thankfully, Historic England comes to the rescue with a little more information.

Our shrouded little man is the ‘Hessey Monument’ (often spelled as ‘Hessay’), carved for Charles Ellis Hessey, probably carved by his brother, Mark Hessey from Portland stone. However, save for a name, the rest is a mystery. A frustrating result for such a phenomenal grave!

Cemeteries are wonderful places. They’re alive with wildlife and history, veritable libraries of people and social history – good and bad. They also offer solace from the hustle and bustle of city living, wherever that city may be.

***

Liked this post? Then why not join the Patreon clubhouse? From as little as £1 a month, you’ll get access to tonnes of exclusive content and a huge archive of articles, videos and podcasts!

Pop on over, support my work, have a chat and let me show you my skulls…www.patreon.com/burialsandbeyond

Liked this and want to buy me a coffee?

To tip me £3 and help me out with hosting, click the link below!

https://ko-fi.com/burialsandbeyond

***

Further Reading and references –

https://www.yorkcemetery.org.uk/cemetery-map

https://dalesbred.weebly.com/blog/category/all

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1259315?section=official-list-entry

Leave a comment