Portobello Cemetery is a relatively modern burial ground on the outskirts of Edinburgh, opened in 1877 and in continual use to modern day. While a Victorian cemetery doesn’t seem to be especially ‘new’, compared to the city’s most famous kirkyards and burial spaces which span centuries of history, it really is a shiny, recent addition.

Located just off Milton Road in the suburb of Joppa, the cemetery was initially designed by architect Robert Paterson, and featured a simple looped path. As the city’s population grew, the cemetery itself was extended twice and now covers 8 acres with new burials continuing on a semi-regular basis. The earliest part of the cemetery features a stunning variety of grand Victorian monuments and interesting epitaphs, whereas newer sections include a variety of war graves and the later inclusion of Edinburgh’s Muslim cemetery.

While a suburban cemetery rarely has a string of A-lister burials within its walls, Portobello certainly has an impressive list of notable interments. Some notable graves include:

Ian Charleson (1949-90) was a Scottish actor and singer, most renowned for his performances in the 1981 film Chariots of Fire and in 1982’s Ghandi. An accomplished theatre actor, he died just two months after portraying Hamlet in Richard Eyre’s production at the Olivier Theatre. Charleson was suffering from AIDs related complications for a long time and ultimately lost his life to the virus. Unusually for the time, he had insisted that news of his death be announced alongside the cause. In doing so, he hoped to raise awareness of HIV and AIDS patients, and promote understanding and sympathy towards those suffering.

LTC William Robertson (VC) (1865-1949) was a Victoria Cross holder, having received the highest order of award for gallantry in the face of enemy fire. He received the VC for his part played in the Second Boer War when he was aged 35. According to a report in the London Gazette:

“At the Battle of Elandslaagte, on the 21st October, 1899, during the final advance on the enemy’s position, this Warrant Officer led each successive rush, exposing himself fearlessly to the enemy’s artillery and rifle fire to encourage the men. After the main position had been captured, he led a small party to seize the Boer camp. Though exposed to a deadly cross-fire from the enemy’s rifles, he gallantly held on to the position captured, and continued to encourage the men until he was dangerously wounded in two places.”

Born in Lancashire, Sir Horace Edward Moss (1852-1912) was a theatre impresario and founder of the Moss Empires Ltd theatre company. While not a well-known brand today, at its peak, Moss Empires had over 50 venues to its name and made an enormous impact in the world of variety theatre. Curiously, Moss theatres were the first brand to introduce the concept of pre-booking, as before this, variety theatres operated on a first-come-first-served basis.

Celebrities aside, I encountered several beautiful headstones on my morning traipse around the grounds.

The Urquhart grave is one of the first to be found at the cemetery’s entrance and memorialises several family members, including a war death – Lieutenant William Thomas Urquhart, of the 1st battalion Sherwood Foresters who was killed in action on the 6th July 1917 aged 32. Thanks to the Imperial War Archives, a little of William’s life is accessible to us all. Born in Edinburgh, his first war posting was to Abassia in Egypt, before joining the Australian Imperial Force and later, the Foresters. At the time of William’s death, the 2nd, 1/5th and 1/6th Battalions were fighting in France, attacking the German lines east of Cite St. Theodore, near Lens, France. This particular attack continued for several days with the Foresters enduring massive losses.

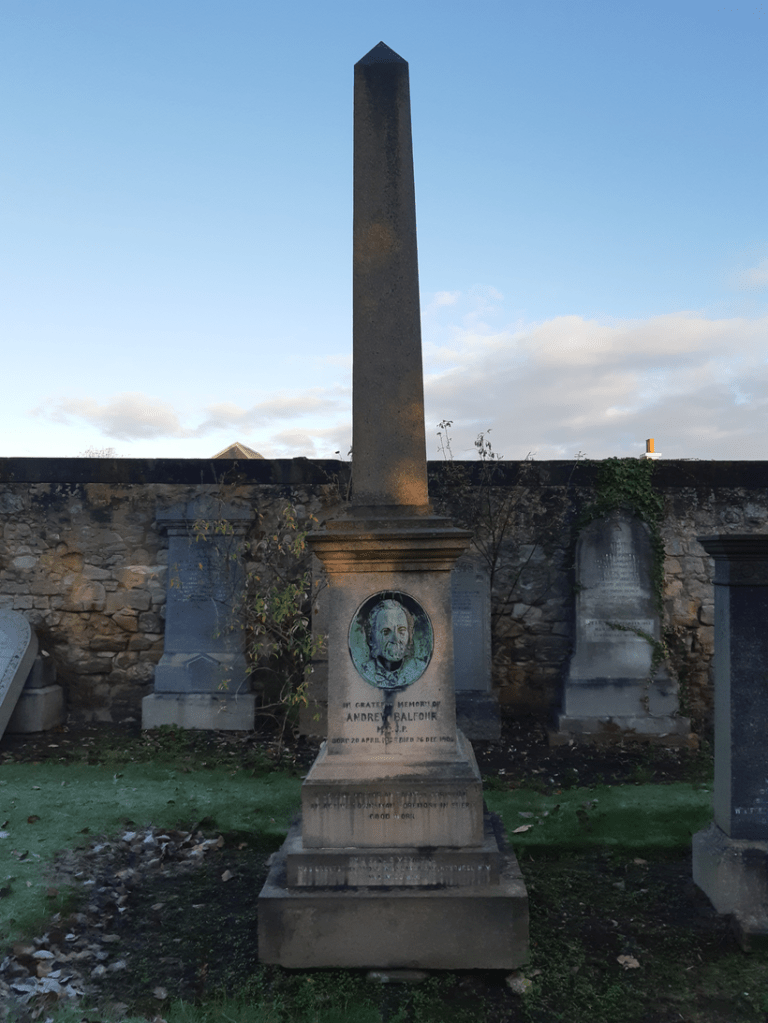

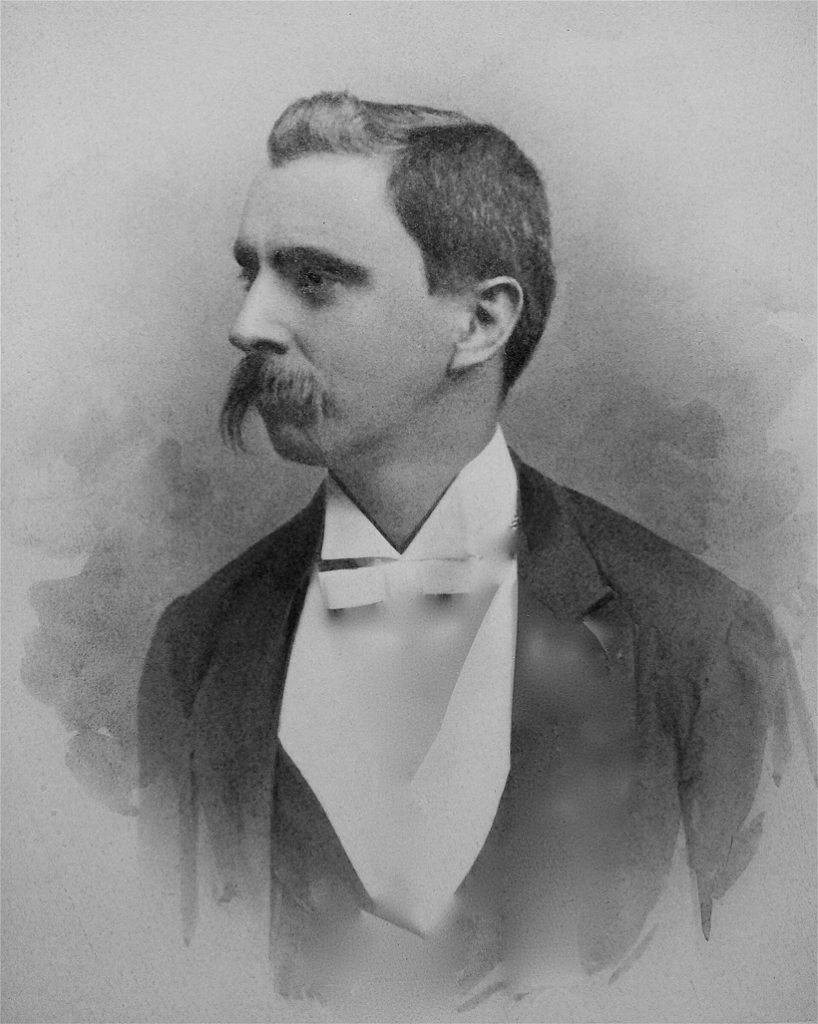

The grave of Andrew Balfour MD JP (1852-1906) is a grand obelisk with a well-sculpted brass likeness of his face in the centre. Balfour was an esteemed physician, being the local GP of Portobello, police casualty surgeon and later, medical officer for the Portobello district of the Edinburgh parochial administration. He also founded the Portobello Working Men’s Institute, ran Bible classes, and was superintendent of the children’s services for over 20 years. In short, he was a tremendous over-achiever. He spent much of his time with the working classes and was primed to assist on the poor-law committee, yet died after attending just one meeting. At the time of his death, he held over 30 official appointments and left behind a wife and four adult children, all of whom were enjoying professional careers.

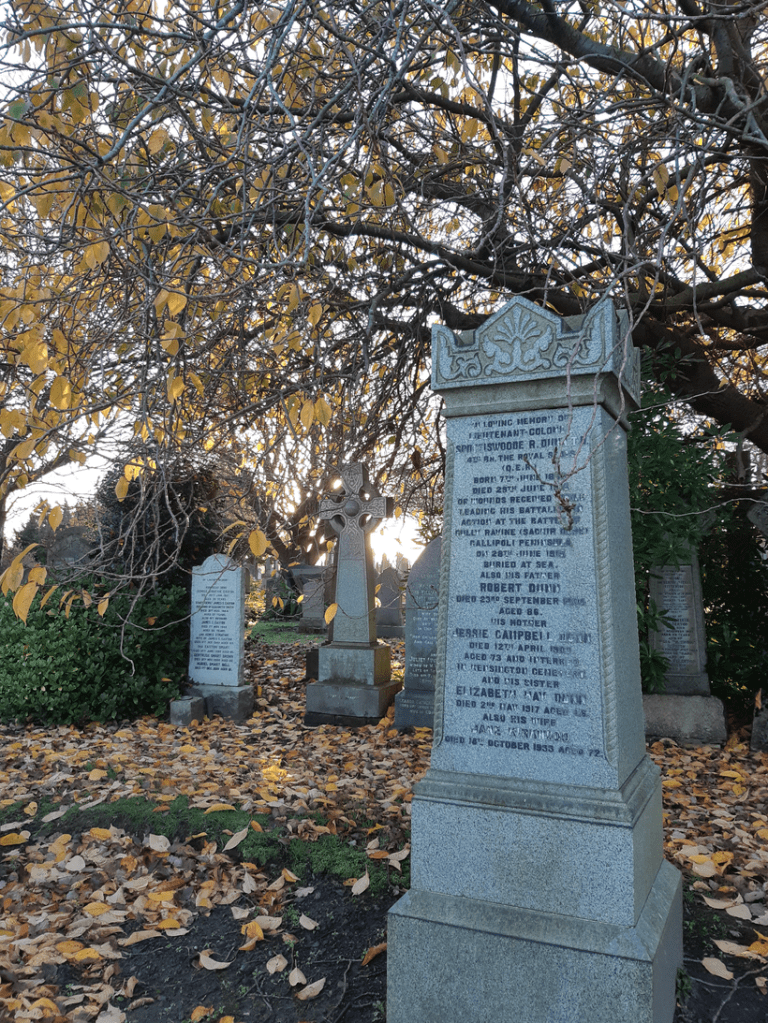

Another military grave that piqued my interest was that of Lieutenant Colonel Dunn, whose death was recorded on his epitaph as ‘who died of wounds received while leading his battalion in action at the battle of Gully Ravine, Gallipoli…Buried at sea.’ Dunn died in 1915 while leading a battalion of the Royal Scots in the Dardanelles. According to war records, during an attack ‘The Fourth Royals were only just out of their trenches when Lieut.-Colonel Dunn fell, wounded by a bullet, but his voice was still clearly heard: “Go on, Queen’s!” The first trench was stormed, and the few Turks remaining in it alive were quickly accounted for… and later, Lieutenant Grant helped Colonel Dunn as far as he could, and then crawled back for stretcher-bearers. Unhappily the Colonel was afterwards struck again and killed before he could be taken to the rear.’

It appears that the colonel actually died on a hospital ship, joining the 204 other men killed during the day’s fighting.

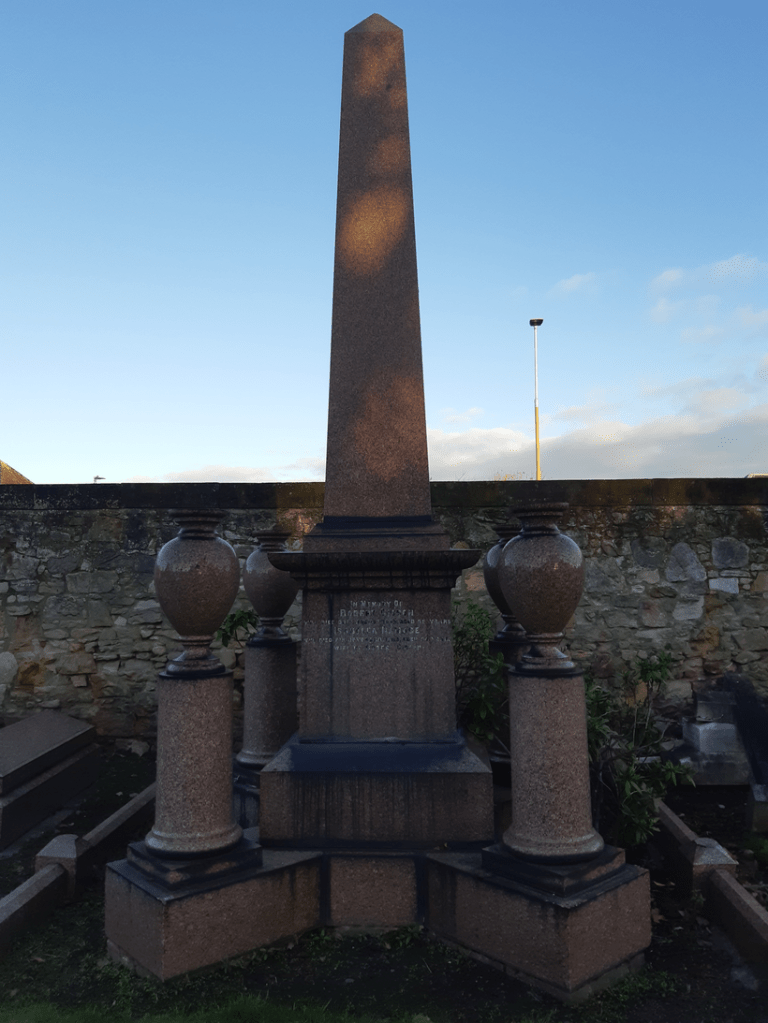

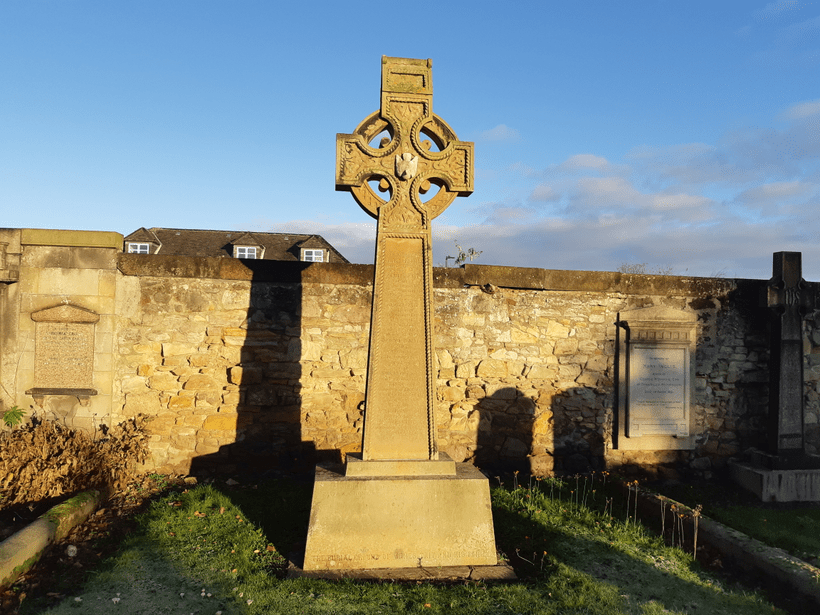

Other grand memorials include a huge pink granite affair by the outer wall, marking the grave of Robert Gibson, some fallen memorials to Robert Smith’s family, an enormous Celtic cross and a grave of Alfred Nichol and Mary Bevan.

There are countless military-related graves throughout the cemetery, including many Commonwealth War Graves, memorialising young lives cut short.

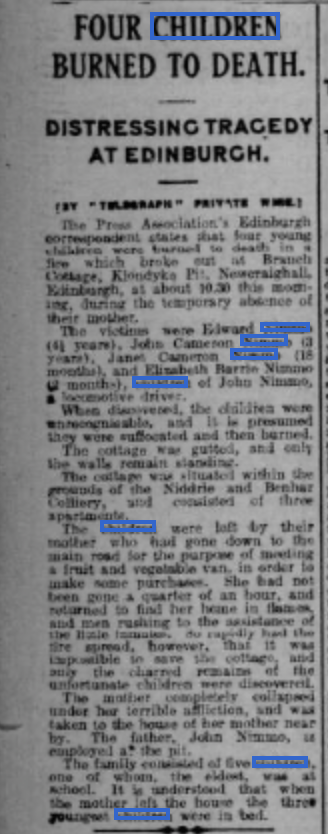

One of the saddest graves in the cemetery is a mass grave to several young children (and later, their parents) who ‘died as the result of a fire at Newcraighill’ on 25th January 1927.

‘IN LOVING

AND AFFECTIONATE MEMORY OF

OUR DEAR CHILDREN WHO DIED

AS A RESULT OF A FIRE AT

NEWCRAIGHALL 25TH JANUARY 1927

EDWARD KEENAN NIMMO

AGED 4 1/2 YEARS.

JOHN CAMERON AGED 3 1/2 YEARS

JANET CAMERON

AGED 14 MONTHS.

ELIZABETH BARRIE

AGED 2 MONTHS

ALSO THEIR FATHER

JOHN NIMMO

DIED 18TH APRIL 1964

AGED 73 YEARS

DEAR HUSBAND OF

MARGARET KEENAN

DIED 2ND JANUARY 1965

AGED 66 YEARS.’

Erected by their Father and Mother through the kind generosity of the public.

So great was the tragedy that it made headlines across the country, even reported in my hometown newspaper of the Grimsby Telegraph. The fire took hold at the cottage of John and Margaret Nimmo, at 10.30am while Margaret had quickly walked down the road to buy fruit and veg. By the time the fire was discovered, the house was fully ablaze and nothing could be done, the house was gutted and all the children – save for the eldest who was at school – had passed. The funeral was recorded in local news, where ‘three little white coffins’ (one containing two children) were laid out at their grandmother’s house. En route to burial at Portobello Cemetery, a gathering of around 150 mourners followed the funeral cortege, with crowds lining the streets. The grave was adorned with piles of wreaths from strangers, who had all been touched by the Nimmo family’s tragedy. John and Margaret Nimmo died within a year of each other in 1964 and 5 respectively, joining their children at Portobello.

The war grave of G Stobie of the Royal Scots is close by and, unusually, commemorates a death outside of large national conflicts. Stobie died on 12th July 1921 aged 26.

Born in Portobello, George Stobie Jr was the son of George and Jane of Southside Cottage, Drummore, Musselburgh. During the inter-war period, the second battalion of the Royal Scots were sent to Ireland to serve in the Anglo-Irish War, where they would remain until January 1922. While another battalion had been sent on imperial service to Myanmar in 1919, it may be more likely that Stobie died during service in Ireland, however information about his death is not forthcoming.

Close to Stobie’s grave are a selection of tall headstones with epitaphs in relief. While this isn’t as exciting as a mausoleum or sinkhole, I found it to be quite an unusual feature as most text is flat or recessed within the stone itself.

One of these graves with a pleasant design was to Samuel Chisholm, son of William and Margaret Shepherd, who died aged 12 on 19th February 1916. Buried alongside his parents and siblings who all made it to old age, he spent decades in Portobello cemetery before the rest of his family joined him.

A beautiful war grave, one not maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, is that of Private Dugald F. Telfer of the 2nd Scots Guard who died at the battle of the Somme in September 1916.

Private Telfer’s memory lives on through a series of unexpected memorials. While he is included at the memorial at Thiepval, he also has a memorial clock in his name at Lady Haig’s Poppy Factory in Edinburgh. Rather fittingly, Poppies (worn for remembrance in November) have been made at Lady Haig’s factory since 1926 and continue making poppy wreaths by hand today.

The Telfer family grave is another particularly sad affair, where Parents James and Agnes died aged 71 and 75 respectively, but joined their children Margaret who died aged 17 and James, Agnes and Robert, all of whom died in infancy.

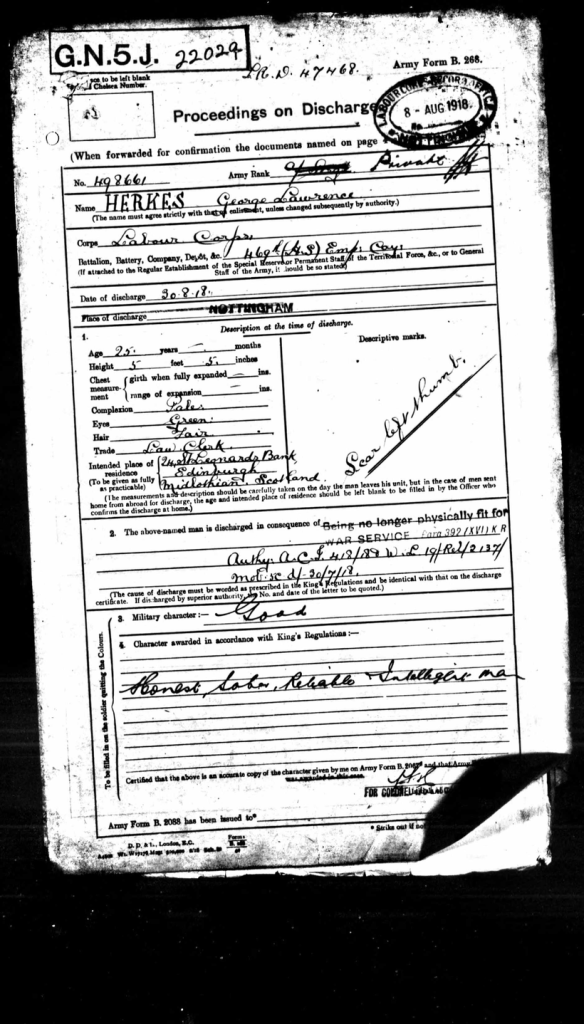

Close by, George Lawrence Herkes of the Black Watch rests, having died on 4th November 1918 aged 25. A local Edinburgh boy, he joined the labour corps and -like so many young men – lost his life during wartime. According to his military discharge record, he was 5 ft 5in with green eyes and had worked as a law clerk before conflict broke out. George didn’t die during active conflict, but was discharged in July, regarded as no longer ft for military service and died just a few months later, back at home in Edinburgh. He had signed up aged 22 on 25th November 1915 and died a week short of armistice day.

Other headstones feature occupations – one of my favourite things to spot. John Smith, who died on 22nd September 1879 aged 65, was a Bathing-Coach proprietor. ‘Bathing Coach’ would most likely refer to bathing machines used between the 18th and 20th centuries, which were huts on wheels, used at seaside resorts to allow people privacy to change into their bathing clothes, before slipping into the sub-zero temperatures off the Scottish coast. Bathing coaches were another fun relic of the complicated world of Victorian etiquette and ideas of decency.

Similarly, Robert Logan, a painter from Portobello, bears his occupation proudly in death.

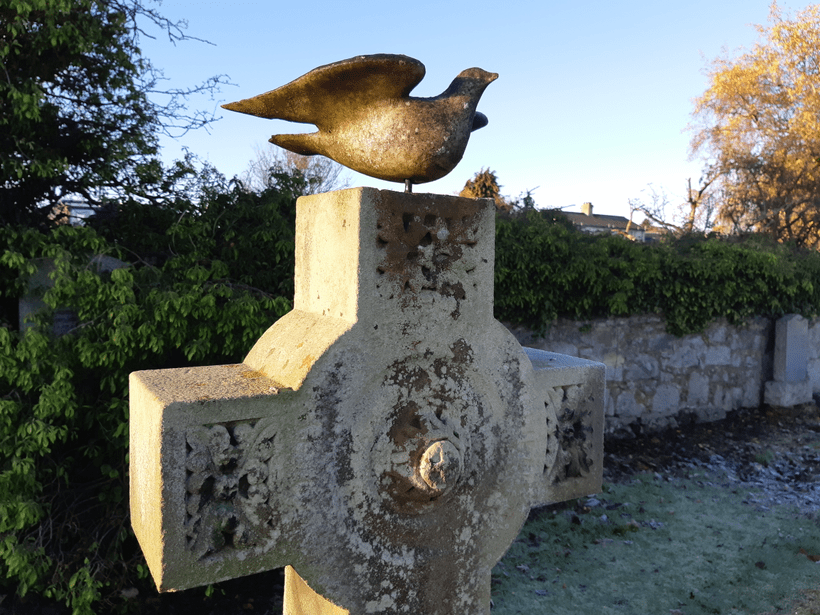

Another striking and unusual headstone belongs to the Robertson family. While the family are commemorated with a simple cross, it is topped by a rudimentary podgy dove, attached with a metal bolt. James Robertson is also commemorated alongside his profession – a blacksmith. The nearby Butler grave – another Butler was also a blacksmith – also features the addition of a podgy stone dove, which I particularly enjoyed spotting.

Robert Kellock has a simple headstone. A former justice of the peace and magistrate, he died at Portobello on 8th February 1915, aged 69. The headstone was ‘erected by fellow members of Regent Street United Free Church and Other Friends in Portobello’; clearly a well-loved man. According to the Portobello Directory 1889-90, Kellock was a merchant and involved in several local council projects, fully immersing himself in the local life of a councillor.

Art Master Alexander Dandie has a more celtic-inspired headstone, which may reflect his own creative interests. Born on 29th November 1861, he died on 6th July 1939. Born in Kirkcaldy, Fife, he was a ‘Teacher of Drawing’ for most of his life, previously having worked as a lithographic artist, according to the 1891 census.

In these images:

Private P. Kane of the Royal Munster Fusiliers is another of Portobellos 27 war dead.

Towards the back of the older part of the cemetery, over a ridge, are a group of scattered graves, some of which were marked in more unconventional ways.

One such grave was marked with two markers of ‘D.L’, and two small plaques. This grave bears the plaque ‘To the memory of Robert Langlands 1951, his wife Jessie 1988 and their family are buried here.’ A simple, small sign seems to mark a plot of multiple burials including a young boy. A very poignant, broken shield caught my eye. It appeared home made or could be regarded as folk art. It reads ‘In loving memory of our dear wee son, John L. Langlands aged 3 years 9 mths. Accidentally killed Feb 20th 1931. Sadly Missed.

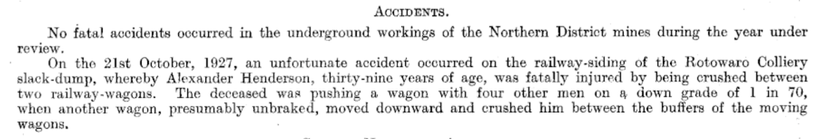

A dense family memorial nearby reports the premature deaths of two brothers, for different reason. Private John Henderson of the 11th Highland Light Infantry was killed in action in France at the Battle of Loos on 25thSeptember 1915, aged 31. His brother Alexander died ‘as the result of an accident at Rotowaro Colliery’ in 21st October 1927 aged 39, and is interred at Kimihia Cemetery, New Zealand. Via the national library of New Zealand’s Parliamentary Papers and Mines Statement of 1928, we can learn a little more about the accident that took Alexander’s life. His death was not due to a collapse, but was a freak incident whereby he was crushed between two railway wagons – he and some men were pushing one, and another wagon behind them did not have the brakes applied and crashed into him.

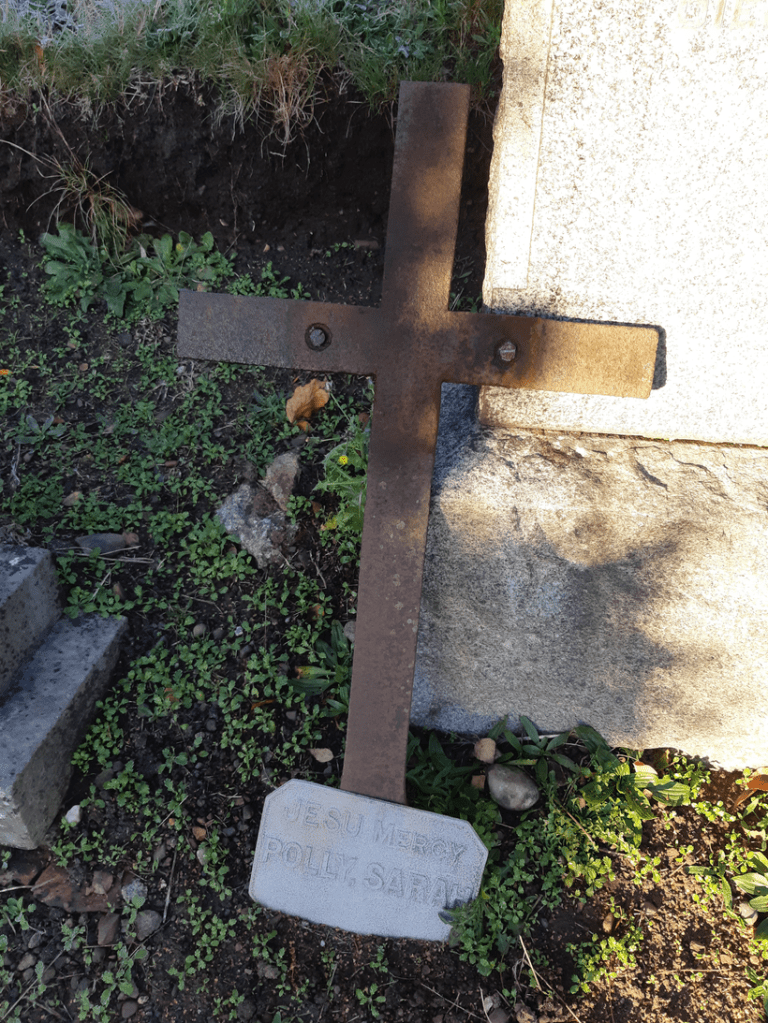

One headstone has two iron markers beside it, one of which appears to memorialise a nun.

It reads ‘March 25th 1933, Dorothy Mary C.S.A.S. Sister of Mercy, Jesu Mercy’. While her name can be found on a catholic prayer list, I can find little else about her life. The other iron cross beside hers reads simply ‘Jesu Mercy, Polly, Sarah.’ A little further into the cemetery, another iron marker reading ‘Jesu Mercy, Katherine, Agatha, Margaret, Mary, Ellen’ suggests one of two things – paupers or nuns.

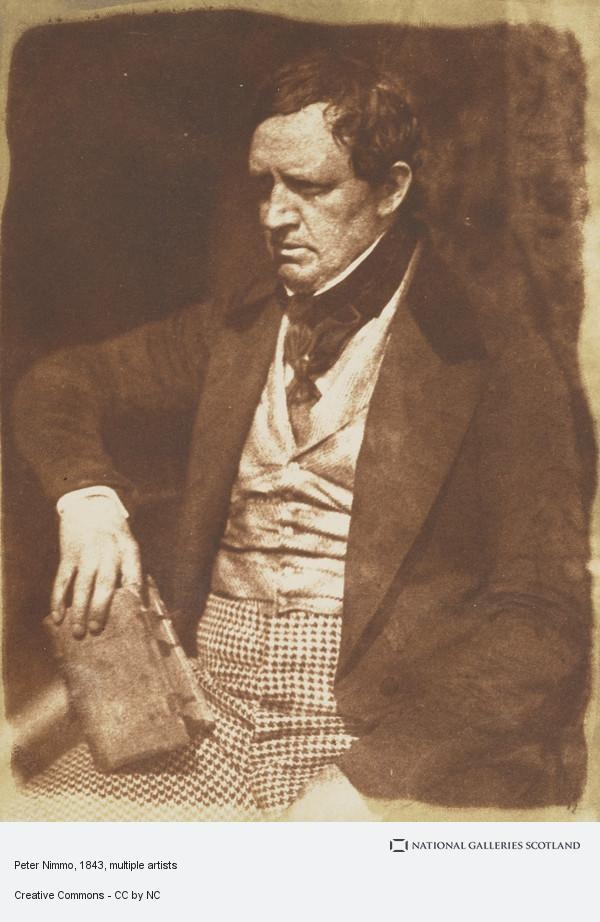

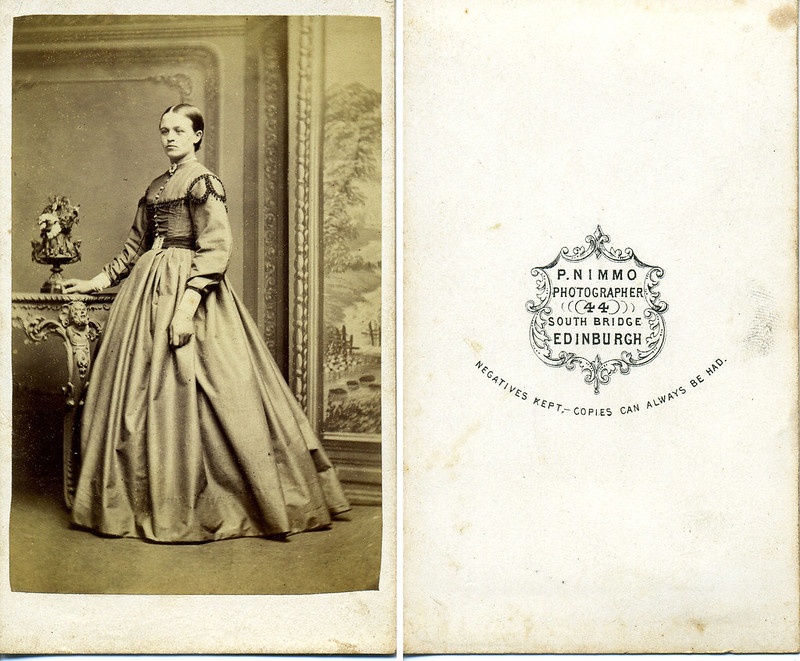

A bright white grave marks the resting place of Peter Nimmo and his family, including grandson James Nimmo who died at Epsom War Hospital in 1916 aged 29.

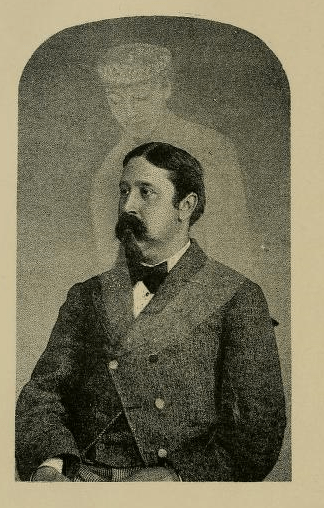

Peter Nimmo was a renowned photographer with studios on Edinburgh’s South Bridge.

Unlike many photographers of the era, many of Nimmo’s photographs remain in contemporary museum collections, including the Nation Galleries of Scotland, where a salted paper print from 1843-1847 can be found on their online archives.

According to Edinburgh Photography historians, Nimmo worked as a commercial photographer at 44 South Bridge, Edinburgh (now a bubble tea café) and formed a company with his son in 1869, which operated until 1896. He also contributed 4 photographs to the 1876 EPS Open Photography Exhibition.

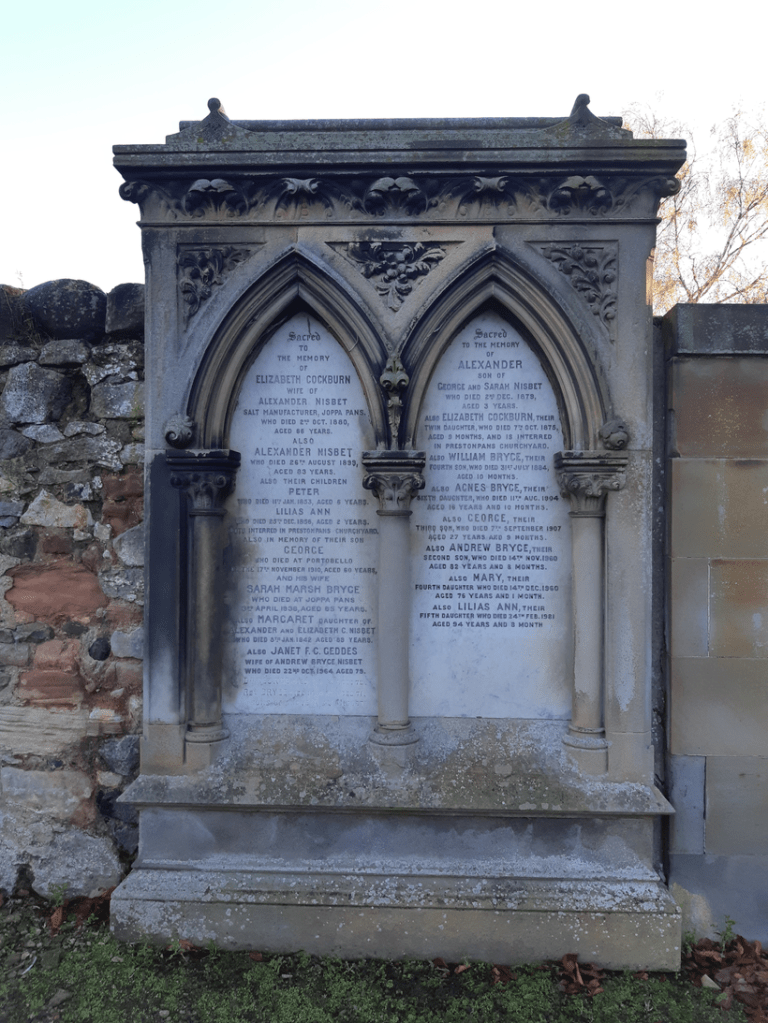

The Nisbet memorial is a veritable wall of text, with a great number of children recorded as dying in their infancy. Focusing on unusual jobs, Alexander Nisbet, patriarch, was named as a ‘salt manufacturer’ at Joppa Pans. Extracting salt isn’t as simple as digging it up, but was harvested via an industrial process. According to Portobello Heritage trust, “The production of salt by evaporating seawater gathered in large pans using coal from the shallow local mines had been carried on in Joppa since the 1630s, part of an extensive industry along both shores of the Firth of Forth… Late in the 19th century Joppa Salt Pans and the houses were taken over by the firm, Alex. Nisbet and Son, who also owned the salt pans at Prestonpans and Pinkie. They later formed The Scottish Salt Co. which went on producing salt at Joppa until 1953 when the last salter, Mr Towers retired.’

According to his obituary, Alexander was a kindly man, an ‘enthusiastic liberal’, a volunteer and politician.

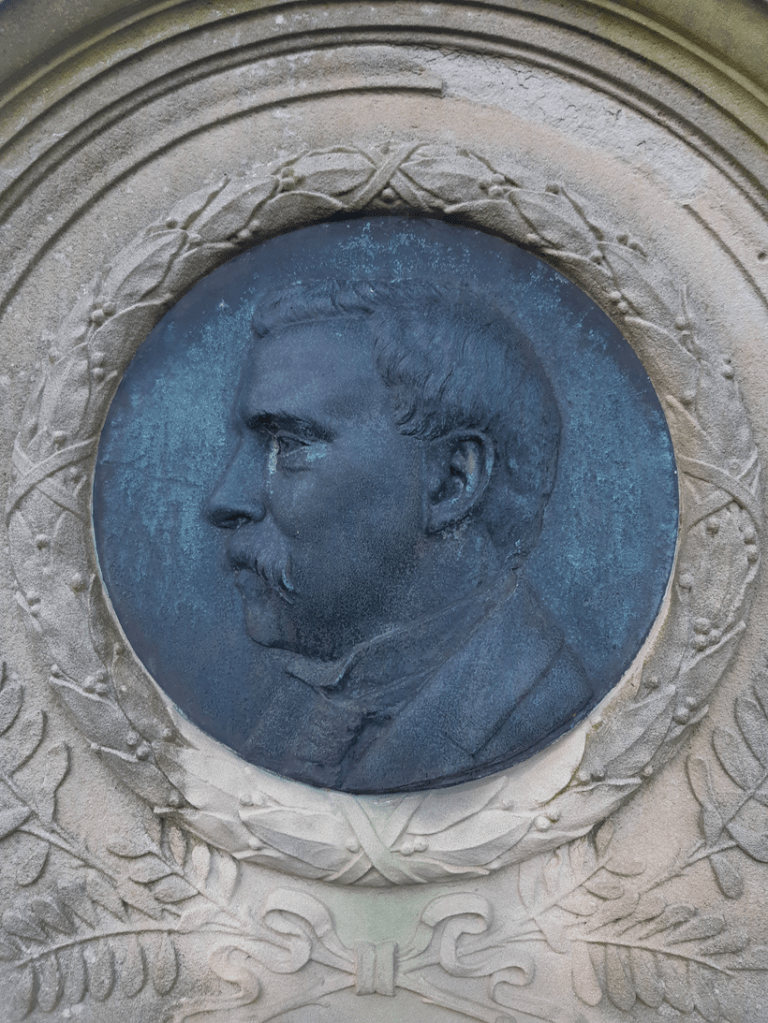

Towards the end of the older cemetery, a handful of opulent memorials stand out. One features a medallion with a likeness of a man’s face, memorialising a man with far too many letters after his name.

This is the grave of Col. Ivison Macadam V.D: F.R.S.E: F.I.C: F.C.S: etc. Brigade Major Forth V.I. Brigade, Lecturer on Chemistry in Surgeons Hall and New Veterinary College. Born 27th Jan 1856, died 24th June 1902. Born with the forename William, he was known by his middle name of ‘Ivison’ throughout his life.

In short, an over-achiever, an antiquarian, scientist and author. He somehow also found time to be colonel to the 1st Lothian Volunteer Infantry Brigade and a Freemason. He was a huge advocate for the education of women, encouraging their education at Surgeons Hall and New Veterinary College, Edinburgh, despite women being banned from most educational establishments in the UK.

Rather tragically, his life was cut short aged 46 when a gunman entered his laboratory at Surgeons Hall and killed both Ivison and a student. A porter and army pensioner at Surgeons Hall, Daniel M’Clinton opened fire in Macadam’s laboratory, shooting at anyone he could see. Macadam was shot in the back, while a young student, James Bell Forbes, entered the room and was shot, dying a few hours later. According to newspaper and court reports, the assailant had planned to take more victims, but surrendered his rifle after persuasion by Macadam’s younger brother. Daniel M’Clinton was charged with double murder, which should have carried the death penalty at the time, but was reduced due to his ‘impaired mental state.’

Macadam was mourned with an enormous public funeral with troops, horses and tens of thousands of locals lining the streets. A Scotsman article from 26th June reads:

“From the house the coffin was carried by eight sergeants to a gun carriage provided by the Edinburgh City Artillery and drawn by six horses with riders. On the coffin was placed the deceased hat and sword. It was a four-mile procession from his house at Lady Road to Portobello Cemetery “to the solemn strains of the Dead March from “Saul” heard swelling in the distance… as the escort … proceeded in slow step…”

And while I’m sure Portobello hides many more fascinating lives, deaths and memories, this post is already VERY long. I’ll leave you with the lingering images of a few frosty graves.

***

Liked this post? Then why not join the Patreon clubhouse? From as little as £1 a month, you’ll get access to tonnes of exclusive content and a huge archive of articles, videos and podcasts!

Pop on over, support my work, have a chat and let me show you my skulls…www.patreon.com/burialsandbeyond

Liked this and want to buy me a coffee?

To tip me £3 and help me out with hosting, click the link below!

https://ko-fi.com/burialsandbeyond

***

Leave a comment