A place called ‘Postman’s Park’ doesn’t exactly scream ‘historically relevant and poignant memorial space’, but life continues to surprise us all. This little public garden in the middle of London is rather unassuming by both name and initial appearance – another pretty, cultivated green space in the middle of the capital, offering a little solace to commuters in the hustle and bustle of the ever-rotten rat race.

However, look a little closer and some plaques by the flower beds give a little nod as to the park’s true purpose. One reads ‘Christ Church, Newgate Street. This burial ground was laid out by order of the vestry. Sept. 10th 1883 Rev. T.D.C. Morse M.A . vicar. John Mixer, William Pitman, church wardens.’ A burial space it may be, but there are few headstones to admire, save for a handful flanking the modern buildings at the park’s perimeter. However, a glimpse of coloured glazed tile indicates the beginning of a stunning and poignant display of lives lost in ‘heroic self-sacrifice’. Beginning with a small upright plaque, the purpose of the unique memorial space is laid out

‘G. F. Watts’ Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice

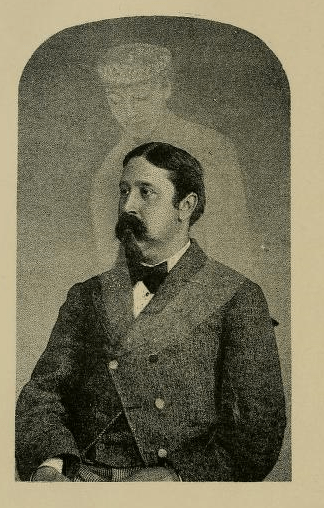

Unveiled in 1900, the memorial to heroic self-sacrifice was conceived and undertaken by the Victorian artist George Frederic Watts OM RA (1817-1904)

It contains plaques to those who have heroically lost their lives trying to save another.

Watts believed that these ‘everyday’ heroes provided models of exemplary behaviour and character.’

The park sits on the former site of St Botolph’s church, Aldersgate, and later grew to include the graveyards of St Leonard’s on Foster Lane and Christ Church, Greyfriars. The space grew a little more following the demolition of a handful of on-site houses and was fully formed by the late 19th century.

The small park is just a stone’s throw from St Paul’s Cathedral an sits in the shadow of huge blocks of flats and offices. Regarded as a public park and one of the largest green spaces in the capital, Postman’s park is actually the amalgam of three separate burial grounds. Like so many other urban burial spaces, these inner-city burial spaces were packed so densely with bodies, with so little soil in-between, that this desperate need for burying space resulted in the ground sitting 4 feet higher than the surrounding area. Following the cholera outbreaks of 1831 and 1848, church graveyards simply couldn’t keep up with the stacks of bodies that overwhelmed their parish, with fresh burials being regularly exhumed to make room for more fresh bodies. The stench from these sites was unimaginable, and with a society still basing much of its public healthcare system on miasma theory, city officials were moved to instigate burial reform (and the age of garden cemeteries and the Burial act of 1852 soon began.) Horrifically, this Royal Commission sent to investigate burial grounds recorded the plight of gravediggers across the capital, who were frequently ordered to ‘shred’ bodies in order to fit them into the available space.

Following the Burial Act, inner city graveyards were closed to new interments and in 1858, the churchwardens announced their intention to ‘ plant, pave, or cover over the churchyard and burial-ground.’ Also, families who wished to disinter and rebury their loved ones had a month’s notice, and would have to do so at their own cost.

After years of redevelopment and levelling, the park opened in October 1880 and was immediately popular with local workers. A few years later, when the final burial ground was included, workers had to raise the ground level once more to meet the steep incline of centuries of London’s dead.

It seems unusual that so many churches were demolished close by, however the culprit wasn’t secularism or town planners, but infamous historical tragedies. St Leonard’s was all but destroyed in the great fire of London in 1666, with the ruins standing long into the 19th century. The building was deemed too far gone to merit rebuilding, and so the parish was merged with the nearby Greyfriars; a church rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren after the great fire, but later destroyed during WWII. St Botolph’s at Aldergate underwent several transformations, surviving the Great Fire, but ultimately demolished in the mid-18th century and rebuilt in 1790. Strangely enough, although the living parishes merged, each church continued to operate its own separate burial ground. The park managed to survive the cold hands of mid-century town planners, and in 1972, parts of the park were Grade II listed and preserved for generations to come.

The link to postmen seems tenuous – what’s that about?

Rather uninspiringly, the name ‘Postman’s Park’ relates to the sites ownership, rather than any wholesome Royal Mail functionality. For many years, the exact ownership of the site was the subject of legal dispute, with church authorities, the Treasury, the City Parochial Foundation and the General Post Office all staking their claim on the site. Today, it is operated by the City of London Corporation and is gated and locked at night to discourage more nefarious activities

In 1900, the park was to welcome its most unique and profound set of memorials; the George Frederick Watts’ Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice. In 1887, the artist George Frederic Watts wrote to The Times, proposing to ‘collect a complete record of the stories of heroism in every-day life’, producing a memorial as part of the Golden Jubilee celebrations of Queen Victoria. Sadly, Watt’s suggestion came to nought during the Jubilee year. However, in 1898, the Vicar of St Botolphs at Aldergate took Watts up on his suggestion, following the purchase of the park land. A new fundraising appeal for an additional £3000 was launched, stating that Watts would make a covered walkway, with space for many small memorial tablets celebrating the heroism of ordinary Londoners.

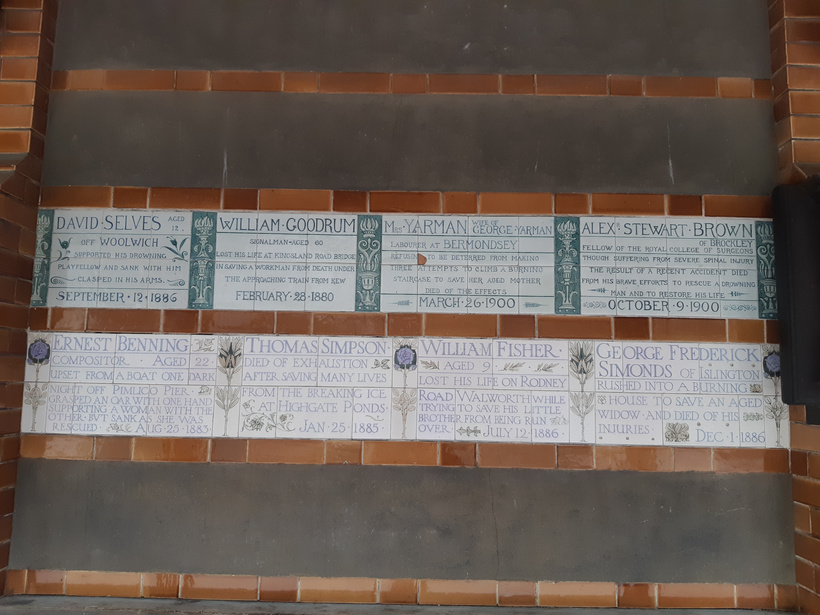

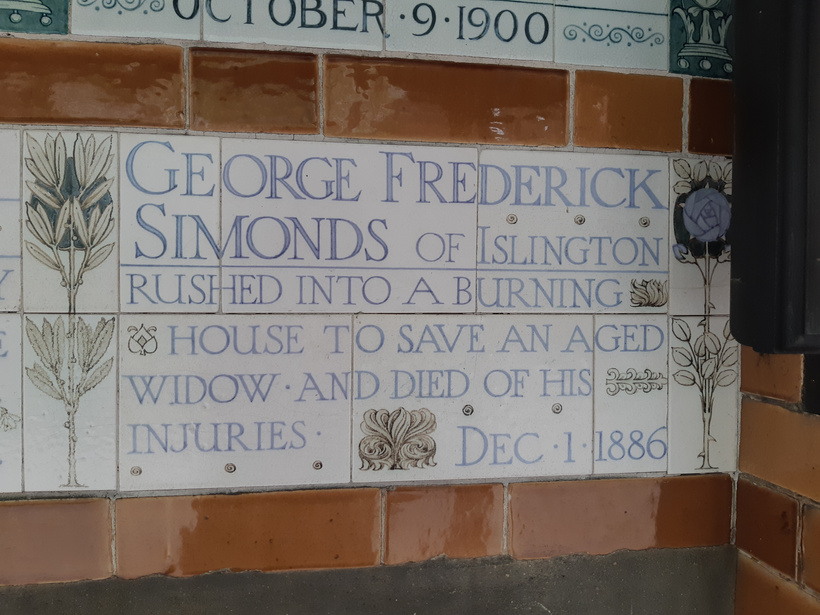

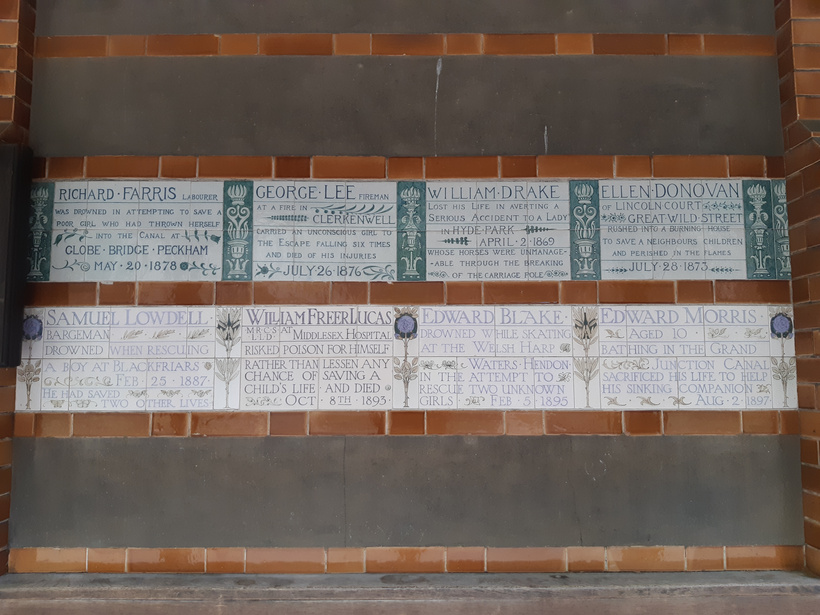

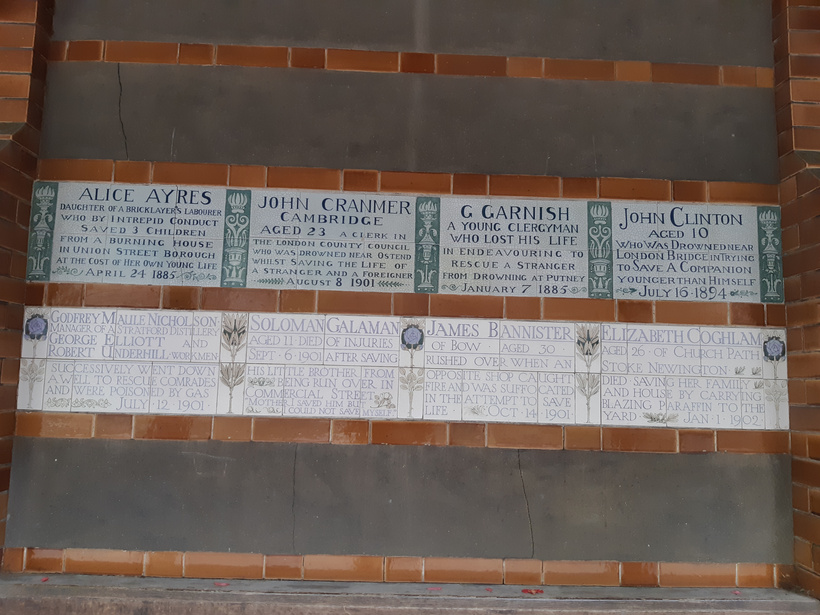

After various unavoidable administrative issues, construction began in 1899, and the new park with new, shiny memorial, was opened to the public in 1900. Sadly, Watts, then aged 83, was far too ill to attend the grand opening and was represented by his wife. Although Watts’ original plan was for more conventional plaques, hand-painted glazed tiles were chosen as the material of memorialisation as they were far cheaper and easier to produce than elaborately carved stone. Although this was a cost-cutting exercise, this artistic choice made the memorial a unique and striking piece of art, unlike anything else in the capital. The first four plaques were formed of two tiles, costing £3 5s when completed, leaving much space and funding available for the projected future additions.

The individuals whose stories adorned these first plaques were personally selected by Watts, who had been keeping a miniature archive of his own, retaining newspaper clippings of selfless deeds. Although Watts passed away in 1904, his list of heroics was consulted by the ‘Heroic Self Sacrifice Committee’ for several more years during the project’s progression.

While the rest of London submitted to the lure of industrialisation and mass production, William De Morgan, the leading tile designer of the age and producer of the tablets, was keen to retain the hand-painted nature of the plaques, despite the immense cost and instability of his own business. Later tiles were produced in more simplistic styles by Royal Doulton, much to Morgan’s dismay.

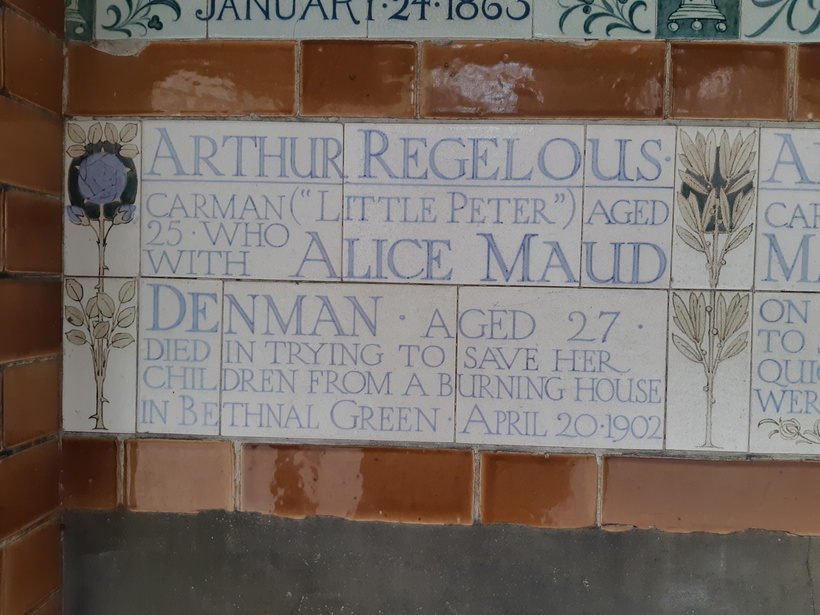

You can while away an hour reading the condensed epitaphs to strangers. Here’s just a few of my favourites –

‘Mary Rogers. Stewardess of the Stella. Mar. 30. 1899. Self sacrificed by giving up her life belt and voluntarily going down in the sinking ship.’

‘John Cranmer, Cambridge, Aged 23. A clerk in the London county council who was drowned near Ostend whilst saving the life of a stranger and a foreigner. August 8 1901.’

‘Samuel Rabbeth. Medical officer of the Royal Free Hospital who tried to save a child suffering from diptheria at the cost of his own life. October 26th 1884.’

‘William Goodrum. Signalman – aged 60. Lost his life at Kingsland road bridge in saving a workman from death under the approaching train from Kew. February 28 1880.’

‘Frederick Alfred Croft. Inspector. Aged 31. Saved a lunatic woman from suicide at Woolwich Arsenal Station, but was himself run over by the train. Jan 11 1878.’

‘Elizabeth Boxall. Aged 17 of Bethnal Green who died of injuries received in trying to save a child from a runaway horse. June 20th 1888.’

‘Solomon Galaman. Aged 11. Died of injuries. Sept 6 1901 after saving his little brother from being run over in Commercial Street. “Mother I saved him but I could not save myself.”

Although most tablets were installed around the turn of the century, examples commemorating feats of bravery in WWI and beyond were installed. Watt’s vision for a full wall was never envisioned, however those that stand today attest to the strength of the human spirit and the kindness of strangers.

***

Liked this post? Then why not join the Patreon clubhouse? From as little as £1 a month, you’ll get access to tonnes of exclusive content and a huge archive of articles, videos and podcasts!

Pop on over, support my work, have a chat and let me show you my skulls…www.patreon.com/burialsandbeyond

Liked this and want to buy me a coffee?

To tip me £3 and help me out with hosting, click the link below!

https://ko-fi.com/burialsandbeyond

***

Leave a comment