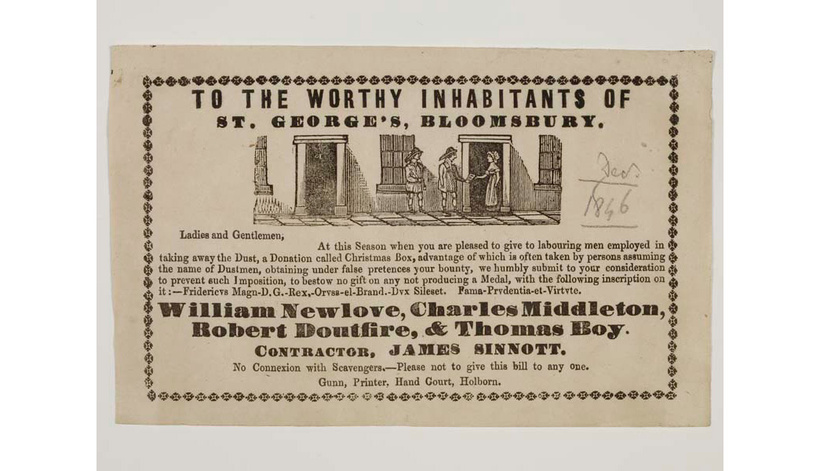

Giving refuse collectors a small Christmas bonus seems an obvious nicety of the season, but before the mid-19th century, they went home with empty pockets and no Christmas bonus to help with the costs of festivities. In 1846, four London dustmen printed up stacks of handbills to post through the doors of residents on their rounds.

The four men – William Newlove, Charles Middleton, Robert Doutfire and Thomas Boy – addressed their plea to the ‘worthy inhabitants of Bloomsbury’, asking for a donation to be sent directly to the men themselves, and warning of con men and thieves pretending to be dustmen in order to steal cash.

‘To the Worthy Inhabitants of St. George’s Bloomsbury.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

At this Season when you are pleased to give to labouring men employed in taking away the Dust, a Donation called Chritsmas Box, advantage of which is often taken by persons assuming the name of Dustmen, obtaining under false pretences your bounty, we humbly submit to your consideration to prevent such Imposition, to bestow no gift on any not producing a. Medal, with the following inscription on it :- Fridericvs Magn-D.G.-Rex,-Orvss-el-Brand. Dvx Sileset. Fama-Prvdentia-et-Virtvte.

William Newlove, Charles Middleton, Robert Doutfire, & Thomas Boy.

Contractor, James Sinnott.

No Connection with Scavengers, – Please not to give this bill to any one.

Gunn, Printer, Hand Court, Holborn.’

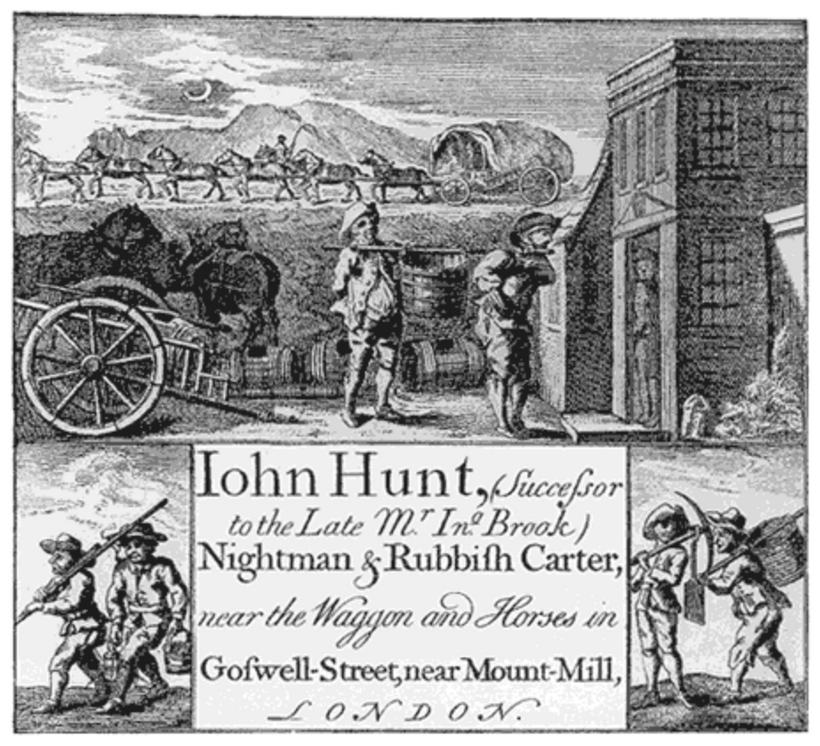

Topped with an image depicting two men handing the flyer to a woman in a bonnet at her front door, we can only hope that the men were successful in their requests. In the 19th century, waste removal services were operated differently to today; they weren’t council-run services, but private enterprise. Independent companies and individuals would offer their services to districts, ultimately retrieving their rubbish AND their sewage.

All waste, whether domestic or something more pungent, would then be sold on. Hard goods and rubbish would be sold as salvage, whereas the buckets of urine they collected would be sold on to tanners for use in leather production. Faeces would be taken outside of London and sold to farmers as manure. This practice would continue for a few more years until London’s sewage system was revolutionised following the ‘big stink’ of 1848.

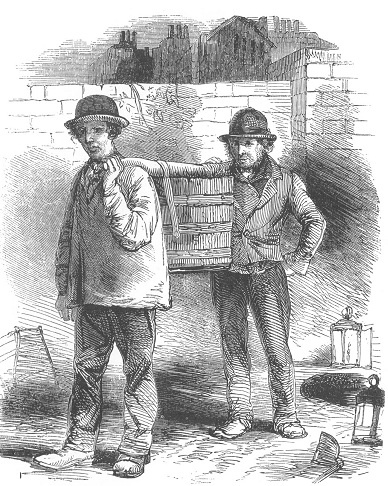

Men who specialised in the collection of human waste were called ‘Night Soil Men’ (with ‘night soil’ meaning ‘poo’) and were known to arrive at nightfall, performing the thankless task of freeing Londoners from their buckets and wells of faeces, filled with tonnes of whiffy ‘night soil’. While this job seems to be a grim and fantastical role from another world, for those living in city slums, the night soil men were a very real presence. My grandfather grew up in the slums of Nottingham and spoke often of the arrival and stink of the ’10 O’Clock Horses’, or if we’re being Nottingham specific , ‘The 10 o’clock ‘osses’. However, I had no context for what they were and feared the arrival of these nightmarish night-horses – I had to be asleep before the horses came, otherwise…well, we never really got that far.

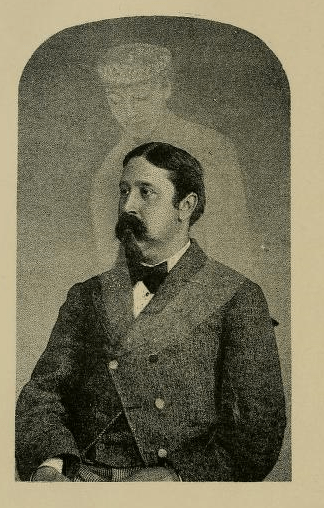

As another fun personal fact, my great grandfather Arthur (that’s him under ‘Council’ with the big ‘tache) was a binman in Cleethorpes around the 1920s, and although it wouldn’t have been the easiest job (little surprise he died aged 55), I take a little solace in the fact that most Cleethorpes houses had introduced rudimentary plumbing into their houses some years prior…

***

Liked this post? Then why not join the Patreon clubhouse? From as little as £1 a month, you’ll get access to tonnes of exclusive content and a huge archive of articles, videos and podcasts!

Pop on over, support my work, have a chat and let me show you my skulls…www.patreon.com/burialsandbeyond

Liked this and want to buy me a coffee?

To tip me £3 and help me out with hosting, click the link below!

https://ko-fi.com/burialsandbeyond

***

Leave a comment