After reading yet more Victorian periodicals, I found myself descending into a spectral blush-based rabbit warren.

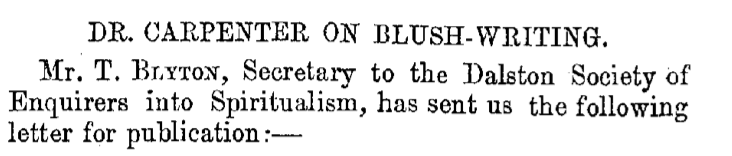

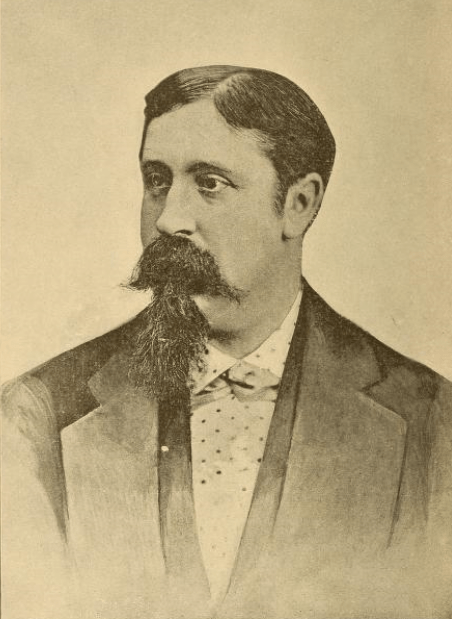

In the age of materialisation mediumship, where mediums conjured all manner of matter from the ether, prominent mediums and parapsychologists sought to both categorise and record the breadth of phenomena. In the 1870s, arguably the leading spiritualist group in the UK was based in Dalston, London. Known as the ‘Dalston Society of Enquirers into Spiritualism’, the group began meeting in 1865 at 74 Navarino Road and quickly established themselves as a leading voice and bolthole in the fast-developing Spiritualist movement. Many of their members were enterprising businessmen as well as spiritualists, one of whom – William Henry Harrison – went on to found The Spiritualist periodical; one of the leading and most important sources of authentic 19th century spiritualist voices. The Dalston group’s cash cow, or leading light, was young medium Florence Cook – a teenage superstar of Spiritualism who went on to become the UK’s leading name, complete with spirit guide and handful of scandals. However, while I could wax lyrical about Cook’s legacy, and her treatment at the hands of inquiring spiritualists and scientists, today’s post comes at the hands of the secretary’s (Thomas Blyton) reportage in an 1872 issue of The Spiritualist.

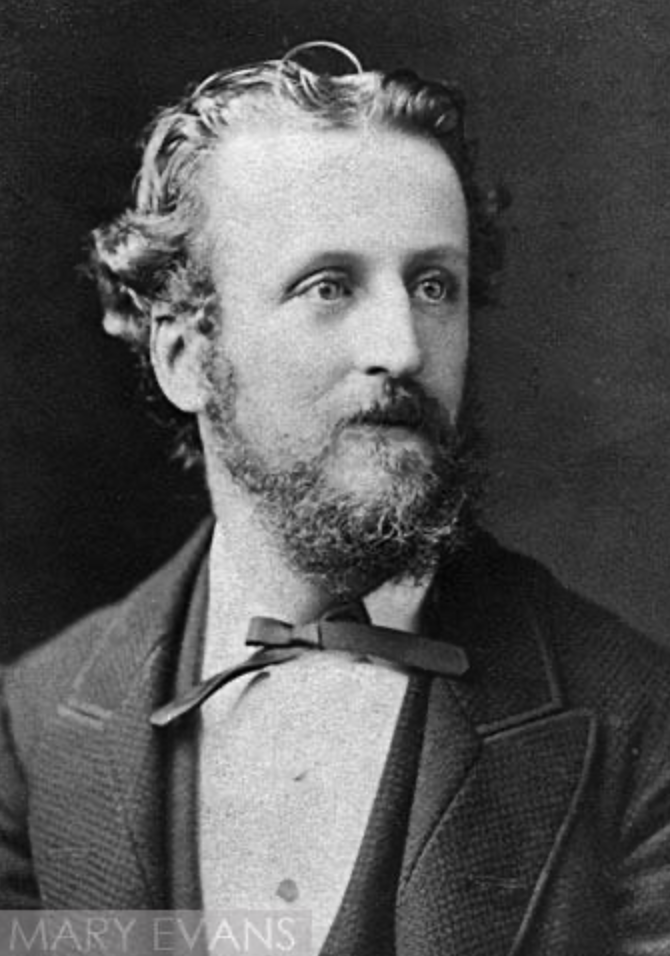

Submitted to The Spiritualist was a short sequence of correspondence between Thomas Blyton, Secretary and Treasurer, and Dr W. B. Carpenter, M.D., F.R.S., &c. &c., Registrar of London University and President of the British Association.

Blyton reported some recent claims from the séance rooms of Herne and Williams (prominent mediums and mentors) that baffled even the most experienced and ardent spiritualists. Instead of simple productions of spirit matter (spirit guides, spirit hands, apports from the ether and the like), new manifestations were reported by sitters to their seances, the likes of which had not been seen before. Instead of conveying names and titles through verbal means, they claimed that ‘names appear and disappear upon their flesh like a blush.’ Quite the feature, and one that would not be out of place in a contemporary horror film.

However, Blyton was not writing to Dr. Carpenter for insight, but in response to Carpenter’s own dismissal of the phenomena. In the Quarterly review, Blyton claimed that the Dr stated that ‘the trick by which the red letters were produced was discovered by the enquiries of our medical friends.’ But exactly who were these friends, and what were they saying?

Carpenter was less chatty in his response, but berated Blyton for basing his letter on ‘an assumption which you have no right to make, and which has brought upon me charges of deliberate falsehood and other heinous moral offences which I do not choose to degrade myself by refuting…’. In short, he claims the article was simply presumed to be by him, and public naming had sullied his reputation by embroiling him in this blush-based discourse. Not his most believable claim. However, he regarded the ‘blush-writing’ incidents to be ‘so-called spiritual manifestations’, and, after a little flattery, he finally decided to weigh in with his blush knowledge.

Blush-writing was the subject of much medical excitement a few years prior when one ‘Mr Foster’, an American medium, exhibited such a dramatic demonstration of psychical phenomena. As a medical professional, or physiologist, Carpenter posited that ‘the ‘blush’ might be produced by a strong impression on the mind of the ‘medium’, analogous to that which produces the ‘stigmata’ in cases similar to that of Louise Lateau…’.

Indeed, many cases of religious ecstasy and stigmatics are regarded as instances within which a mental phenomenon (devotion, extreme emotion) is externalised through physical wounds. Could a medium reach such a state of spiritual ecstasy that their own thoughts became imprinted in their skin? The Louise Lateau referenced was a famous mystic and stigmatic of the 1860s who repeatedly suffered the wounds of Christ from her feet and side without clear cause. For those not believing in their divine cause, physicians believed that such wounds were mentally self-inflicted due to extreme religious ecstasy and a focus on the appearance and sensation of the crucifixion. In attaining a sense of spiritual bliss, perhaps similar wounds or sensations could be replicated, yet to have the appearance of English letters seems like a far greater escalation, with far weaker source material.

However, while a mystical explanation would be preferential to those seeking any incident of spiritualist legitimisation, reality seemed rather more terrestrial. According to Carpenter’s own experiences, the same effect could be achieved by a schoolchild with a plastic protractor. He stated ‘If letters or figures are traced with any pointed instrument upon a smooth tense skin (such as that of the fore-arm usually is in plump subjects), and its surface be then rubbed with the fingers, the letters will come out in a red blush, fading after a short time.

Carpenter noted that when he watched the American medium Mr Foster, he frequently rubbed at his forearm to ‘bring out the markings’. His attempts at surreptitiously creating these marks were – reportedly – poorly masked by his ‘fidgety’ nature during the séance itself. His recommendation to the Dalston spiritualists was to watch the hands of the mediums, or the self-styled ‘blush-writer’.

While Blyton’s correspondence with Carpenter was printed in full by The Spiritualist, the editor himself couldn’t leave the column untouched without a heavy asterisk and a footnote. Attributed to the editor alone, the addendum reads: ‘Mr. Blyton, of course, knows as well as we do, that Messrs’ Herne and Williams have no control over the blush-writing. Dr. Carpenter’s theory then is :- 1. That the medium gets the name of the deceased person by reading it from unconscious twitches of the face of the questioner (see Quarterly Review). -2 That unseen by the observing questioner he scratches the name on his arm. -3. That it then appears and disappears like a blush. We suggest that he do all this at his next lecture at the Royal Institution. – Ed.’

A confrontational summation perhaps, and one keen to defend Herne and Williams – two men who were bastions of the movement at this time. There are indeed many ways in which we can read this comment. However, it does not appear that Carpenter pursued any further line of blush-writing inquiry in his lecture series.

And naturally, dear reader, I have spent the last twenty minutes trying to gently carve the word ‘cake’ into my forearm, rubbing at the marks with little success. Perhaps if I possessed a little more spiritual prowess, my blush-writing abilities would be greater. But until then, I must retain my seat on the sofa, and rub at my cake-carved arm with disdain.

And as for Herne and Williams? While their reputations as prominent mediums continued to grow, they did not appear to add blush-writing to their spiritual arsenal.

So why were the Dalston group publishing this correspondence when Dr Carpenter clearly stated that this was intended as a private conversation? We can only speculate. However, I personally feel that the Dalston group were settled in their status as a prominent and relevant society and were keen to keep their names in everyone’s mouth. In publishing such correspondence regarding a new phenomena, their name is prominent within every letter and ever letter page of the periodical. Much like Simon Cowell’s approach to marketing boy bands in the 2000s, I believe that in the case of Dalston, any press was good press.

Just 10 days after the publication of Carpenter and Blyton’s letter exchange, a similar correspondence was published in The Spiritualist, and one with a far more terse approach.

Carpenter pulls no punches – ‘Sir,—I cannot but feel extremely surprised that you have thought yourself justified in giving publicity, without my express sanction, to a correspondence in which I allowed myself to be drawn, in the belief that you were simply and honestly seeking for scientific information. The last of my letters was the only one you had any right to publish; since it was this only which had reference to the subject of your original inquiry…’

Carpenter’s issue was that, firstly, private correspondence had been published without his knowledge or permission. Secondly, that the information was printed verbatim, without expressly demonstrating that the purpose of such knowledge (regarding the manner in which blush-writing can be practised) was to apply it critically in the ‘detection of a suspected fraud’. By publishing the explanation immediately after it dropped through the Dalston letter box, the cat was out of the bag, and any chance of catching fraudulent blush-writers in the act was well and truly scuppered. Indeed, ‘if ‘blush-writing’ be a trick, the performers will not now subject themselves to the detection of it.’

Carpenter had a point. By suddenly publishing Carpenter’s debunking this new ‘blush-writing’ trend in full, Blyton had scuppered any chance of investigating its practitioners or even catching them in the act. And unsurprisingly, Carpenter has something to say about the Editor’s summation of his theory.

‘On the two occasions on which I saw Mr. Foster (the American medium) produce the ‘blush-writing’, the names had been previously written on papers at the table at which he was sitting, and in both instances the names were those written by the person directly opposite to him, the movement of whose pencil he could easily follow, even if the writing was concealed from him. When the names were written on another table, the backs of the writers being turned towards Mr. Foster, no ‘blush-writing’ was produced.’

The Dalston society were unrepentant and stated that ‘the best way to stop tricks is to publish how they are done, and upon this plan the Dalston Society has always acted.’. However, this blush-writing debacle brought forward some rather unexpected devotion to the form, and a protection of the aforementioned American medium Mr Foster; a medium that neither the editor of The Spiritualist, or the Dalston society had met.

Nonetheless, tonally, things were to take a more argumentative slant. Whether these defences came from the Dalston group or from The Spiritualist periodical itself is unclear, although it does demonstrate the fanaticism that mediums did – and continue to – inspire.

The original comments of the ‘Quarterly Review’ article, describing Mr Foster the medium’s fraudulent blush-writing, are reframed as bringing ‘unfounded charges against an innocent man.’ Whereby ‘Foster is alleged to have had two ways of getting at the names of deceased relatives of strangers whom he met for the first time. In the one case it is asserted that when the stranger called over the letters of the alphabet, when he came to particular letters he gave unconscious indications, which Foster could read, of those letters being the right ones. The other assertion was that he got the names by watching the motions of the top of a pencil while the bottom of it was concealed from view. People who made real investigations into the nature of Foster’s mediumship wrote the names before they went to him, and took them in their pockets.’ In summary, they believed his blush-writing to be legitimate as they brought along a handful of pre-written papers…

In another instance, written in rebuttal of Carpenter’s debunking, one Mr A. R. Wallace (Presumably Alfred Russel Wallace – a scientist and contemporary of Darwin’s who was sympathetic to spiritualist principles) said:

‘On one occasion Mr. Foster extended his hand upon the table; it was perfectly free from any mark whatever. Gradually a faint red mark appeared on the wrist, which increased till it formed the letter F, remained visible two or three minutes, and then faded away. This was the initial letter of a name Mr. Owen had secretly written on a piece of paper.’[1]

Therefore, as many ‘careful observers’ had already witnessed this miraculous process of blush-writing, Carpenter was deemed an ill-informed dissenter, using his credentials to dismiss the continued wave of legitimate spiritual phenomena.

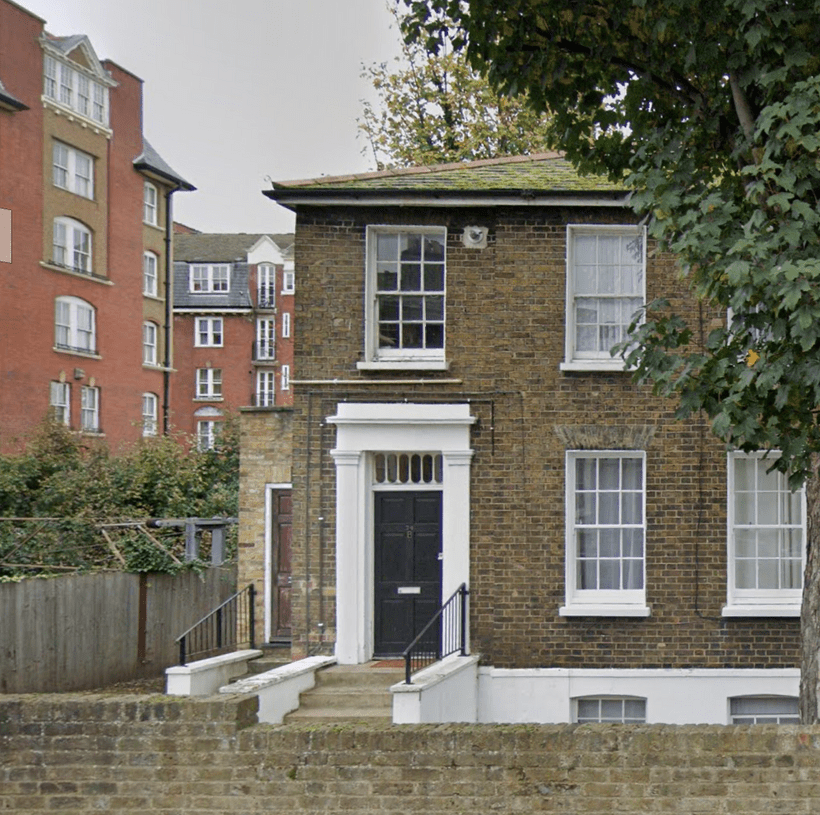

We’ve heard about the blush, and the devotees of Mr Foster, but who was this scribble-covered medium?

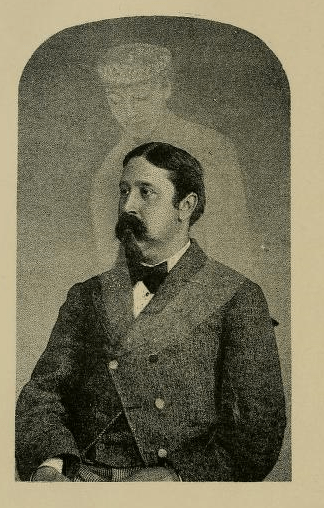

Mr. Charles Henry Foster was born in Salem, Massachusetts (home of the infamous witch trials) in 1838 and became a local sensation in the spiritualist community for his claims of ‘skin writing’, of which ‘blush-writing’ was a variation. Visitors to his seances reported seeing names of spirits appear across his body, not simply across his arms, but also his head. Nor were these messages always in a delicate blush. In 1873, a publication of quite staggering flattery was published, entitled ‘All about Chas. H. Foster, Wonderful Medium.’ The work compiled several articles, claiming to be from disbelievers of Spiritualism who were subsequently converted to Foster’s abilities; much in the vein of ‘I didn’t believe in ghosts until…’. Despite this premise, many of these articles are heavy on the flattery, describing him as ‘full-faced, muscular, handsome – a good-looking blonde-brunette of the order that takes life easily’. In short, Foster was a spiritual knitwear model.

While Foster’s blush and skin-writing abilities are chronicled, as are his so-called ‘Blood Letters’. While this sounds like an excellent death metal band, it appears as a mere escalation of his skin-writing. In one instance, a writer from the New York Era remarks ‘Third, at Mr. Foster’s request we thought of the name of a deceased lady friend, a girl who had been dead for years; and lo! on, or rather under Mr. Foster’s arm, on the surface, there appeared in pink, or blood, the letters of that dead one’s name. We then thought of a male friend, deceased; and lo! his name appeared on the back of Mr. Foster’s baud in blood-red letters.’[2] These remarks of blood, often of a ‘fiery red colour’, are regarded as appearing in initials on Foster’s hands, and are rather more dramatic than the gentle blush scripts of the British reports.

Rather like a massive spectral owl, Foster was also well known for his abilities in ‘pellet reading’ in the mid-19th century. Unlike reading the tiny bones of regurgitated voles, these pellets were tightly-rolled pieces of paper that looked rather like suppositories. Pellet, or billet, reading is one of the most established ricks in the magician or mentalist’s book, where an individual reads messages, envelopes or scripts that are sealed or seemingly inaccessible to the medium themselves. Foster’s method involved taking lots of these pellets (small pieces of paper), mixing them with bank slips, randomly selecting one and revealing the name of the deceased written within. Considering pellet reading was commonplace in stage magic by the mid-19th century, Spiritualist detractors frequently put forward accusations of fraud as they replicated Foster’s ‘spiritual abilities’ with a little sleight of hand, or a well-placed plant in the audience, who could steer the angle of questioning.

Unsurprisingly, Foster experiences several public exposures throughout his career, most notably in 1872 when John W. Truesdell (author and prominent debunker) noted that Foster repeatedly had issues in keeping his cigar lit and was using the lighting of several matches as a diversion for interfering with the billets and reading their contents. Another magician, R. D ‘Hercat’ Chaser, caught Foster in a fraud as he hid fake pellets between his fingers, substituting them for real ones.

As with most prominent mediums, these exposures did little to stop Foster’s career, and his acolytes, who continues to preserve his legacy in articles and a posthumous biography, where George C. Bartlett chronicled his mystical life, describing him as a pseudo-messiah figure and ‘the most gifted and remarkable spiritual medium since Emmanuel Swedenborg.’ In a similarly messianic manner, his biographer remarked of his fortitude in the face of blush-writing. These were described like stigmata, where – when letters appeared on his hand (the colour of ‘blush on the cheeks of a bashful girl’)- he could not refrain from yielding to the impulse to cry out in ideal pain and awe-striking fear.’[3]

While the contemporaneous celebrations of Foster’s blush writing abilities may err on the side of the supernaturally unlikely or completely mystical, a contemporary assessment of Foster’s blush writing claims may not be as dismissive as one may suggest. The medical condition of dermatographia (literally meaning ‘skin writing’) is a common and benign condition whereby an individual’s skin can produce red, raised lines or welts upon the application of pressure or scratching. These marks last from minutes to hours and are caused by the body producing histamine when exposed to light pressure. Believed to affect up to 5% of the population, individuals with dermatographia are theoretically able to ‘scratch’ words into their skin that subsequently appear as raised, red, text. While the production itself may be uncomfortable, there are countless examples online of individuals creating elaborate temporary designs across their skin as a transient source of artistic entertainment. First described as a form of ‘nettle rash’ by physician William Heberden (d.1801), understanding of the condition developed throughout the 19th century until the study of the condition became something of a medical novelty. French physicians employed within Paris’ Salpetriere Hospital furthered research in dermotographia, naming it ‘autographisme’ and later ‘dermographisme’, a forerunner of the modern term. Photographing patients with the condition became commonplace towards the end of the 19th century, as images of skin ‘writing’ were used to illustrate both medical textbooks and popular magazines and periodicals.[4] While much is known of Fosters life, it isn’t clear if he was ever diagnosed with such a condition, however it would certainly explain many of his blush writing feats.

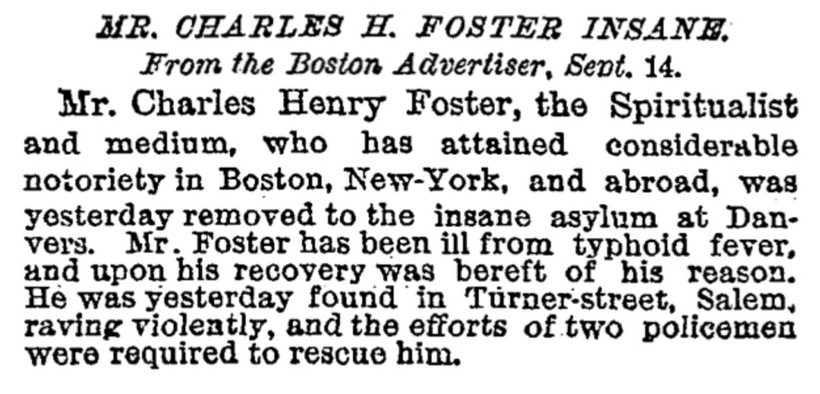

According to Bartlett’s biography, Foster died aged 52 in spiritual bliss, where ‘a calm followed the tempest ; the skies cleared ; the music of the spheres sounded in his ears ; spirit friends, kind and wise, clustered round his bed, and welcomed him with open arms into their fairer state of being. . On entering the spirit-world with health, youth and mental vigor more than renewed, he commences a work beyond all that in his palmiest days could ever have been accomplished through him in the body.’ Other accounts of this life – including a profile by Arthur Conan Doyle – describe his erratic behaviours in more detail, suggesting he was living with an undiagnosed mental illness such as schizophrenia, even spending time in an asylum. Foster died shortly after his release from the institution, when he was also believed to be suffering from ‘typhoid fever’. Regardless of the varying beliefs in Foster’s legitimacy as a medium, we can but hope that his end was peaceful. His curious legacy as the famous, handsome, ‘Salem Seer’ is certainly one to be celebrated.

***

Liked this post? Then why not join the Patreon clubhouse? From as little as £1 a month, you’ll get access to tonnes of exclusive content and a huge archive of articles, videos and podcasts!

Pop on over, support my work, have a chat and let me show you my skulls…www.patreon.com/burialsandbeyond

Liked this and want to buy me a coffee?

To tip me £3 and help me out with hosting, click the link below!

https://ko-fi.com/burialsandbeyond

***

[1] http://iapsop.com/archive/materials/spiritualist/spiritualist_v2_n4_apr_15_1872.pdf

[2] http://iapsop.com/ssoc/1873__anonymous___all_about_chas_h_foster.pdf

[3] http://iapsop.com/ssoc/1891__bartlett___salem_seer.pdf

Leave a comment