In reports of poltergeist activity, as in media,

‘Most modern theories about poltergeists suggests that they are either some form of exteriorisation from children, usually around the age of puberty, or that they are the manifestation of non-human spirits or, more rarely, spirits of known dead persons.’

The drummer of Tedworth, being the first recorded poltergeist report on record, circumvents all of these modern theories of haunting. The 17th century account that established the theory of a noisy, harmful ghost was not rooted in hormonal teenagers, but one magistrate and an irritating percussionist.

As with all such accounts, details vary; some say that Mompesson lived in Tedworth or was simply a local landowner who brought a case against the drummer out of spite alone. Nonetheless, the results are the same.

In 1661, John Mompesson, a ‘landowner, excise officer, and commission officer in the militia’[1](primarily referred to as a ‘magistrate’ in contemporary retellings) was visiting Ludgershall in Wiltshire when he came across a local vagrant called William Drury. William had been making a nuisance of himself in the town, playing his drum relentlessly and begging for money, much to the annoyance of townsfolk. Mompesson confronted the drummer and found him to be in possession of counterfeit documents permitting him to busk. Mompesson brought a case against the drummer and the local bailiff confiscated the drum, but William was relieved to be freed before he was taken to trial.

Mompesson returned home to Tedworth, without another thought for the drummer or his unwelcome rhythms. However, in the interim, the offending drum arrived at the magistrate’s house, forwarded by the bailiff. As soon as the drum arrived at the house, Mompesson’s family were plagued with nocturnal bangs and knocks, hammering on the doors and outside of the building. Above them, emanating from the roof came relentless thuds and drumming.

One night, exasperated by the strange noises, Mompesson chased the sounds through the house with his pistol drawn, but to no avail. After a month had passed, the drumming increased in its ferocity, moving inside the house and terrorising the room where the instrument was placed. This was unnerving enough for the family, but their fear would increase as the sounds began to focus on the children’s’ bedroom.

Loud, animalistic scratching emanated from beneath the children’s beds, their bedframes were beaten, the children shaken and lifted from their beds.

The sounds, and the family’s restless sleep, would continue for two years. The sounds were soon not confined to the night, but rattled about the house in the daytime, objects moving by unseen hands and frightening staff. Like the family they served, they were lifted from their beds, had bedcovers thrown back and their possessions cast about the room. Some were even pinned to their beds, and despite attempts to chase the unseen spirit with swords, the paranormal activity continued in earnest.

Meanwhile, the drumming had become so loud at times that it woke nearby villagers and turned the house into a public curiosity

Inside the house, lights were seen moving about independently while panting sounds and horrible sulphurous smells emanated from unknown sources.

Mompesson wrote that,

‘It would make Chairs, Tables, Trunks & all moveables walk up and down the Rooms. And often come tumble down the stairs, some times [making a noise] like a bowl & other times as if it drew a Chain after it.’

On one occasion, a local priest was brought to the house, alongside several sleep-deprived neighbours. They found that when they prayed in Mompesson’s children’s room, the drumming sounds subsided and moved elsewhere in the house. However, when their prayers stopped, the drumming returned, as did the ‘spirit’s’ anger, which caused chairs to move around the room and hurled shoes and any other loose object it could get its spectral hands on.

On another day, a blacksmith came to stay with the footmen in order to reassure them, but ‘during the night, a pair of pincers was continually snapping at the blacksmith’s nose.’[2]

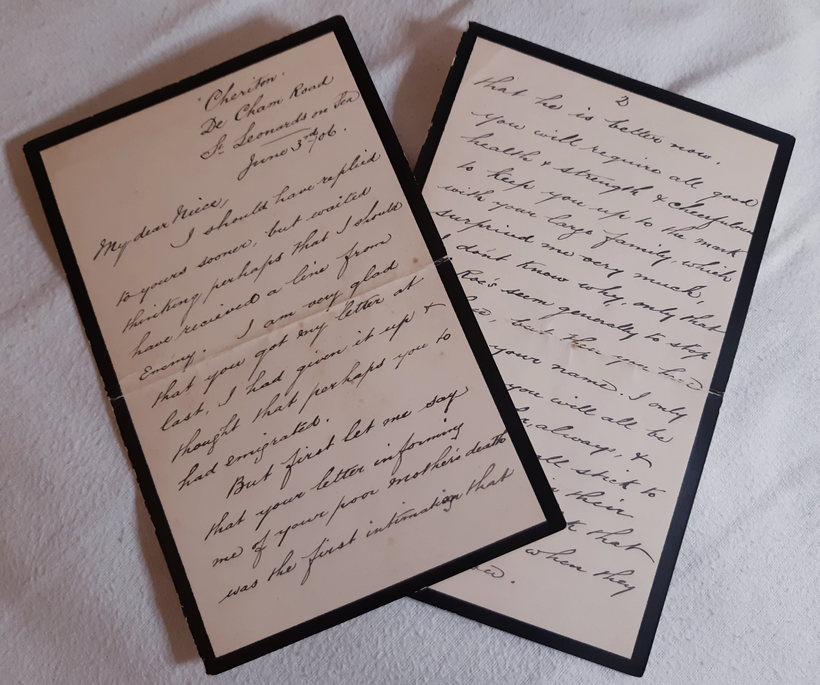

The case gained wider notoriety after Joseph Glanvill, a clergyman, philosopher and demonologist, included a narrative of the story in his book ‘A Blow at Moddern Sadducism. In Some Philosophical Considerations about Witchcraft.’ (1668) Glanvill is regarded as one of the, if not the, first paranormal investigator; publishing his work and hypotheses in his original work, posthumous omnibus and providing inspiration for many other would-be investigators in his stead. Glanvill had visited the family in January 1663, while he was a vicar at nearby Frome (Somerset).

His work is thorough and gripping, but infers the age old excuse that children were indeed too morally pure to be deceptive:

I heard a strange scratching as I went up the Stairs, and when we came into the Room, I perceived it was just behind the Bolster of the Children’s Bed, and seemed to be against the Tick. It was as loud a scratching, as one with long Nails could make upon a Bolster. There were two little modest Girls in the Bed, between Seven and Eleven years old as I guessed. I saw their hands out over the Clothes, and they could not contribute to the noise that was behind their heads.

The general verdict on the drummer of Tedworth is not one of fascination and uncertainty, but variants on the theme of witchcraft, ‘the kids’ or ‘the drummer’s mates’ did it.

One particularly interesting theory is that of Amos Norton Craft (1881) who suggested that travelling communities were to blame:

“Mr. Mompesson had caused the arrest and imprisonment of a member of a band of gypsies, who were intensely enraged at him on that account that the disturbance ceased as soon as the gypsy was transported beyond the sea and his associates had no farther hope of his release; that these manifestations began again as soon as the gypsy returned from transportation; that the gypsy professed to be the cause of the disturbance, and that the excited imagination would naturally add to the manifestations which the enraged trickster really produced.[3]”

H. Addington Bruce, an American journalist, argued that the phenomena were most likely as a result of children’s trickery; considering that much of the phenomena centred around their bedroom, this was no great stretch of the imagination. He was also one of few early critics to recognise that Glanvill had only spent one night in the house, making his experiences incredibly narrow and unreliable.

Despite the case being largely dismissed as historical trickery today, the cultural importance of Glanvill’s work, and the ghostly drummer himself, has been monumental. Even the famous diarist Samuel Pepys, wrote on Christmas day in 1667 that he had been fascinated by the story and regarded it ‘worth reading indeed.’

But what of the drummer? In 1662, William Drury was arrested for theft and sentenced to deportation. While in prison, he confessed to being the cause of Mompesson’s paranormal troubles, but had escaped from the transportation barge before more charges could be brought.

Yet under the Witchcraft act of 1604, the magistrate had his day in court. Mompesson and three other men testified to the ghostly phenomena in court, with a servant saying that he overheard Drury confirming his nefarious actions:

‘Ay, says the Drummer, it was because he took my Drum from me; that trouble had never befallen him, and he shall never have his quiet again, till I have my Drum, or satisfaction from him.’

Although the jurors were torn, for Drury’s previous crimes and thefts, the outcome was the same. The drummer was sent to the American colonies, never to be seen again.

Sources/Further Reading:

A fantastic paper – a critical look on the story’s conflicting narratives.

Hunter, Michael (2005) New light on the ‘Drummer of Tedworth’: conflicting narratives of witchcraft in Restoration England. Historical Research 78 (201), pp. 311-353. ISSN 0950-3471.

https://psi-encyclopedia.spr.ac.uk/articles/tedworth-drummer

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drummer_of_Tedworth

John and Anne Spencer. The Encyclopedia of Ghosts and Spirits. Headline Book Publishing. 1992.

The Drummer of Tedworth: a Halloween tale of witchcraft, demons and an extremely noisy ghost

[1]https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/250/1/Hunter4.pdf p1

[2]https://archive.org/stream/EpidemicDelusions/Epidemic%20Delusions#page/n193/mode/1up

[3]https://archive.org/stream/EpidemicDelusions/Epidemic%20Delusions#page/n193/mode/1up(p192)

Leave a comment