CW: suicide, miscarriage, Byron being Byron.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley was not simply a literary force and creator of Frankenstein (1818), but a tragic, romantic, gothic icon whose exploits in sex and death put the rest of humanity to shame.

Born to philosopher William Godwin and feminist activist Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary’s upbringing was intense and unusual. Her mother died shortly after giving birth to her and she was left to be raised by her father. Godwin was very different in his approach to parenthood, affording Mary a thorough, if unstructured, education, particularly focused around his own anarchist philosophical and political leanings. However, due to her father’s debts, he eventually had to remarry and was wed four years later to a neighbour, Mary Clairmont. Mary had children of her own, and although seemed happy and devoted in her marriage to William, she was volatile and argumentative, and the young Mary gradually distanced herself from family life.

In 1814, aged just 16, Mary entered an affair with 21-year-old Percy Bysshe Shelley, a poet, utter cad, and follower of her father’s political leanings. Percy was already married to Harriet Weaver, with whom he had two children and had romanced since she was a schoolchild. Poor Harriet had an utterly grim life with the 19th century playboy, and I will personally die angry about her fate.

Mary and Percy began their secret liaisons by meeting at her mother’s grave in St Pancras Churchyard, falling desperately in love with one another. As tradition dictates, after the two confessed their love, Mary lost her virginity to Shelley either on, beside or near her mother’s headstone. An action which is both incredibly goth, and a psychologist’s dream appointment waiting to happen.

Surprising no-one but Mary herself, her father was not supportive of this new romance, and desperately tried to keep the two apart and preserve Mary’s reputation. Mary saw the young poet as the personification of her parent’s liberal political ideals, and their reformist ideas of marriage as an oppressive structure. Her father saw him as a financially insolvent married father of one, who had taken advantage of his kindness and come to ruin his daughter. And, as liberal as my personal beliefs are, I’d be inclined to agree.

Shelley had already described his marriage with Harriet as a ‘rash and heartless union’[1]and appears to have been perpetually revisionist in his romantic pursuits; full of the joys of spring in the midst of the romance, but dismissive and cruel thereafter. Mary’s father had banned the poet and pupil from visiting his daughter, but on the 28th July 1814, the young couple fled to France, with Mary’s stepsister Claire Clairmont in tow.

Left behind in the romance’s wake was Harriet, who was pregnant.

After returning to England in September 1816, the couple were poor outcasts with a baby on the way. However, the latter was not to be, and their first child was born prematurely, dying shortly thereafter. In true melodramatic fashion, carnage grew in their wake.

Mary’s half-sister Fanny had committed suicide in October, shortly after their return, supposedly as a result of her own unrequited love for Shelley. And in December, poor Harriet was next, drowning herself in the Serpentine lake in Hyde Park.

In the same year, Mary conceived the idea for Frankenstein at the now-infamous summer excursion to the Villa Diodati in Switzerland, where others such as Polidori and Lord Byron were in attendance. In 1818, the couple left for Italy, where their two children would die, shortly before Mary gave birth to their last surviving child, Percy Florence Shelley.

Suddenly, in 1822, Percy Bysshe Shelley died. His boat, the Don Juan, was caught in a storm when crossing the Ligurian Sea near Viareggio in Tuscany. Ten days later, Shelley’s body and those of his two companions – Edward Elleker Williams and Charles Vivian –washed ashore and were identified by their clothing alone. In his pocket was a small book of John Keats poems, confirming that it was indeed Shelley.

Percy’s body was claimed by a group of several of his literary friends, including the eponymous Lord Byron and poet Leigh Hunt, who organised the cremation of the dead, in order to send the remains to their loved ones. The pyre as much a practical decision as it was an unshakably Romantic one. The compatriots were incredibly taken by classical civilisations and traditional death rituals, including the anointing of the dead with salt, frankincense and wine, and the very romanticised idea of a funeral pyre. Additionally, quarantine laws in Italy commanded that any drowned bodies must be burned. While a furnace was constructed, the bodies were temporarily buried, then disinterred for the cremation itself.

The writers went on to organise a pyre on the beach, and Shelley went on to be cremated on that hot August day. The scene was later immortalised by the artist Louis Édouard Fournier in 1889, albeit depicting far bleaker and gloomy weather than the Tuscan reality. Leigh Hunt’s later account recalls a lone seabird flying overhead and Byron’s strange behaviour following the pyre’s lighting. After the bodies of Williams and Shelley were fully engulfed in flames, Byron – presumably overwhelmed, rather than playful or dismissive – stripped and swam out to sea, missing much of the ceremony.

However, as Shelley’s body burned, his heart did not.

Possibly due to an earlier bout of tuberculosis, the poet’s heart was calcified and scorched, but fully intact within the flames. Shelley’s friend, the adventurer and novelist Edward John Trelawny, reached into the flames and retrieved the heart, burning his hand in the process.

Passing it on to Leigh Hunt, the poet preserved the organ in spirits and refused to give it to the grieving Mary for some time. Considering that Lord Byron had already expressed an interest in retaining Shelley’s skull, this is no great leap of the Romantic imagination.

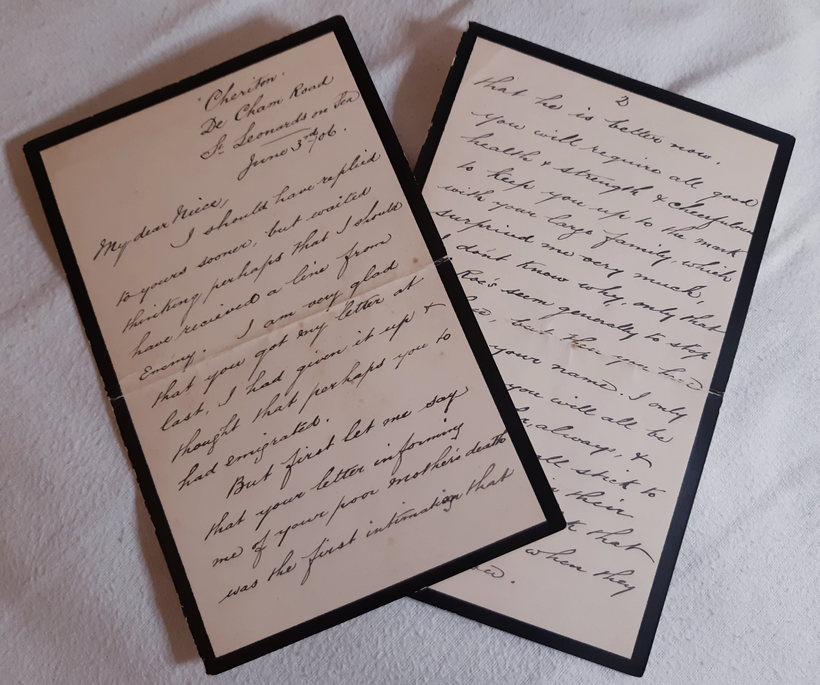

Eventually, after the rest of Percy’s remains had been buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome, the heart was returned to Mary who carried it with her for the rest of her life, wrapped in a silk shroud. Mary died of a brain tumour thirty years later, aged just 53, and was buried at St Peter’s Church, Bournemouth. A year later, the heart was rediscovered in her desk, wrapped in the pages of one of Shelley’s last poems, Adonais.

The heart remained with the family until the death of their son Percy Florence in 1889, when the heart was finally laid to rest in the family vault.

But after all this, was it Shelley’s heart? Scholars and historians remain divided as to whether anyone could have identified a part-charred organ correctly, and that romanticism aided the story. Many argue today that there certainly was a bit of calcified something carried around after his death, with heart and liver offered up as options, but what exactly, nobody knows.

The story of Shelley’s death, and his heart’s life beyond him has fascinated us for nearly two centuries. A young poet burned on a beach and an indestructible heart has an inherent, romanticism that can’t be ignored. So said Sara Davies at the Rosenbach museum and library:

‘On the surface, the story of Percy Shelley’s heart seems like a symbol of poetic expression and a deeply romantic (if morbid) gesture of true love.(…) Mary Shelley’s legacy was to make something enduring and meaningful out of pain and loss–an equally powerful symbol.’[2]

In death, Percy Shelley brought about another unobtainable masculine ideal, but one to which I fully subscribe. If you’re not going to give me your calcified heart to keep beside me for all eternity, then simply don’t bother. I know my worth.

*

Liked this post? Then why not join the Patreon clubhouse? From as little as £1 a month, you’ll get access to four brand new posts every week (articles, pictures, videos, audio) and full access to all content before that! Loads of exclusive stuff goes on Patreon, never to be seen on the main site. Pop on over, have a chat and let me show you my skulls…

www.patreon.com/burialsandbeyond

Sources and Further Reading:

Mary Shelley’s life and work is obviously an enormous and fascinating field of study. Personally, I’d suggest reading Frankenstein (1818), The Last Man (1826) and Lodore (1835) if you fancy dipping your toe into her works.

https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/65624/mary-shelleys-favorite-keepsake-her-dead-husbands-heart

https://rosenbach.org/blog/mary-shelleys-indestructible-heart/

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/account-of-the-death-and-cremation-of-p-b-shelley#

[1]Bieri, James (2008), pp 269-70

[2]https://rosenbach.org/blog/mary-shelleys-indestructible-heart/

Leave a comment