Like many counties, Lincolnshire celebrates an annual open churches festival, in which numerous small villages open their church doors to visitors with a cup of tea and a frightening array of cakes and jams.

One of the churches involved in celebrations was the unassuming-looking parish church of St Michael in the tiny village of Glentworth. Glentworth, a village and civil parish, boasted a population of only 323 in 2011.

Surrounded by immaculately maintained grounds, St Michaels, like most small parish churches, is a small, composite building, with multiple additions made over several centuries. The oldest part of St Michael’s is the Anglo Saxon tower, with later additions made in the Elizabethan, Victorian and Georgian periods. The structure, being predominantly rebuilt in the Victorian and Georgian periods, is beautifully maintained and simplistic in design.

Aside from their annual scarecrow event, the sleepy village of Glentworth seems to be renowned for little else. Which, once you cross the threshold of St Michael’s, is a truly baffling fact.

The interior of the church is plainly decorated, with simple plastered walls, gothic windows and attractive Victorian red floor tiles. The stained-glass windows are understandably more elaborate, with the east wall featuring bright depictions of the crucifixion and last supper.

However, the window itself was built for another purpose; to cast more light upon the tombs beneath it. These tombs, are – without a doubt – the jewel in Glentworth’s crown.

To the left of the window stands the imposing tomb of Sir Christopher Wray and his family. Wray was Chief Justice during the reign of Elizabeth I, and a hardened, controversial Judge. A quick scan across any history book will reveal Wray’s name next to a whole manner of high profile trials including that of John Somerville and William Parry, who conspired to assassinate the queen. However, my personal favourite, with a decidedly grizzly ending is that of the pamphleteer John Stubbs who – after publishing disparaging materials about the English monarchy’s relationship with France – was condemned to have his right hand cut off by ‘means of a cleaver driven through the wrist by a mallet’. Although not especially relevant to Wray himself, I must repeat Stubbs’ morbidly wonderful final words before his hand was removed were ‘Pray for me not my calamity is at hand.’

Most importantly, in historical terms, is that Wray, acting as an assessor, took part in passing the death sentence on Mary Queen of Scots in 1587.

It may seem strange for such an eminent politician to have found his final resting place within sleepy Glentworth, yet one must remember that during the 16th Century, Lincolnshire – Lincoln in particular – was an important political centre. Wray was also Lord of numerous manors across the county

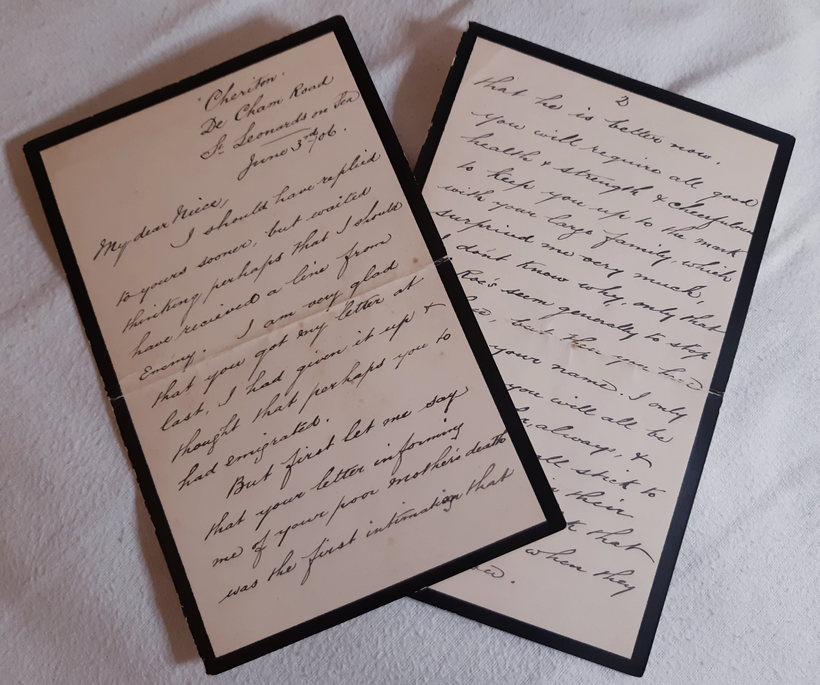

Wray’s tomb is an imposing structure; a marble and alabaster monolith stretching to the very top of the chancel wall. Effigies of Wray and his wife Anne are set back into a niche, with four smaller figures beneath them. These small figures of women, stand around a foot in height and represent Wray’s daughters, two of whom died in infancy.

Above the figures of Wray and his wife, lies a whole host of stunning carved imagery. Acanthus leaves (a popular Greek symbol of immortality) lie at each corner of the inscription, nestled alongside skulls, torches and ribbons. The tomb is remarkably well preserved and maintained, with many of the painted details remaining vivid.

Opposite the tomb, rather overshadowed by Wray and his family, is another beautiful alabaster memorial. Although far smaller, the memorial to Elizabeth Saunderson is similarly filled with well-preserved carvings and striking figures of cherubs, acanthus leaves, crossed bones and hourglasses (see pictures).

Considering the enormous and unusual nature of Wray’s tomb, it is surprising to say that a remarkably similar tomb of full-size effigies lies a stones’ throw away at the village of Snarford. But I’ll leave that jaunt for another time.

Wray’s tomb is a true gem in Lincolnshire’s historical and ‘deathy’ fabric, and I would urge you to pass by if you ever find yourself in the county. The church is open during the daytime and relatively easy to access. Although I can’t guarantee they’ll have cake.

Further Reading:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Stubbs#Trial,_punishment,_and_further_writing

http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1558-1603/member/wray-christopher-1522-92

Leave a comment